“[I]n order to survive what we come up against, in order to build worlds from the shattered pieces, we need a revival of lesbian feminism,” proposes feminist scholar Sara Ahmed in her 2017 book Living a Feminist Life.

Four years later, we can see a growing academic interest in lesbian feminism, exemplified by the 2021 conference “What happened to lesbian and gay studies?” Also, lesbian platforms like Butch Is Not A Dirty Word and WMN zine have been multiplying, including the queer-identified woman-owned store, design studio and event space Otherwild, which creates and sells clothing and housewares often based on archival images from lesbian-feminist activist histories. Recently, we have even seen the first lesbian dating show on mainstream TV, Princess Charming. Of course, we could debate to what extent such a reality show on a private TV channel can be feminist, but I would argue that the huge audience response from (and beyond) lesbian and queer communities also speaks for itself. Candidates like Wiki did not just participate to have a good time, but also because she feels that she has an educational mandate, and she uses her agency to address topics like trans inclusion and anti-racism on German TV.

These examples revolve around lesbian representation, and to some extent they further queer aesthetics and ways of designing. However, on a deeper level, they share a foundation that I would like to explore: the history of lesbian feminist tactics and strategies. How did previous generations of lesbian women deal with encountering heteropatriarchal structures every single day? How did they find each other and build supportive networks? I believe that with regard to developing and maintaining our own feminist communities in the design field, an exploration of lesbian feminist tactics and strategies might be helpful, if not essential.

“Sara Ahmed argues that lesbian feminism is not a matter of the past, like some landmark that we leave behind as we progress towards, and reach, queer feminism.”

Ahmed says, “I write as lesbian. I write as feminist,” and that “to describe oneself as a lesbian is a way of reaching out to others who hear themselves in this as.” I hear myself in this as. Me too: I live a feminist life as a lesbian. I realize that I am constantly searching for thoughts and ideas (and those who formulate them), in which (and in whom) I can hear myself. I am in search of thoughts and ideas that are seldom easy to grasp and articulate, probably because the languages that I have at my disposal have been formed by heteropatriarchy. I am amazed and inspired whenever I come across the work of people who manage to theorize and clearly contextualize the thoughts that seem to otherwise escape me; that seem to otherwise evaporate in front of my eyes as soon as I try to make sense of them, although they are rooted in my feelings and experiences.

Sara Ahmed argues that lesbian feminism is not a matter of the past, like some landmark that we leave behind as we progress towards, and reach, queer feminism. “Lesbians are not a step on a path that leads in a queer direction,” she states. “A willful lesbian stone is not a stepping stone. Try stepping on a stone butch and see what happens.” Ahmed, a lesbian woman of color whose thinking and acting is deeply rooted in feminist intersectionality, speculates if in a heteropatriarchal world there could be anything more astonishing, and indeed queer, than women who center all aspects of their life around other women: “Lesbians: queer before queer.”

“Even if we are all united in our struggle against cis-heteropatriarchy, our differences still matter when it comes to how we can move through this world, and if society in general, laws, and our designed environment [...] support or hinder us in living our lives.”

Many of us want to queer categories, blur boundaries and overcome boxes. We dream of a world in which we can just be ourselves. At the same time, we still live in, and have to deal with, a patriarchal world in which we are socialized and judged according to cis-heteronormativity, white supremacy, ableism, classism and so on. A world in which we simultaneously experience privilege and discrimination, always depending on where exactly we stand in what Patricia Hill Collins calls the “matrix of domination.” The differences in how we experience and navigate this matrix matter. Someone who openly identifies as queer, but is generally—with or without their partner—straight passing, has different experiences and is less likely to face violence than someone who identifies as lesbian and is clearly marked as such as soon as they are seen holding hands with another lesbian; or someone who is butch or stud and is always and immediately seen as such. Identities (whether with regard to gender or sexuality) are of course rarely clear-cut, not necessarily stable, and often in flux. My intention here is also not to play “Privilege and Oppression Olympics,” to borrow Roxane Gay’s words, but to support us in thinking about how those differences matter. I believe that unfortunately the term “queer” alone is not always helpful. In fact, it sometimes even renders these crucial differences invisible. Even if we are all united in our struggle against cis-heteropatriarchy, our differences still matter when it comes to how we can move through this world, and if society in general, laws, and our designed environment (urban space, buildings, clothes, toys, etc.) support or hinder us in living our lives.

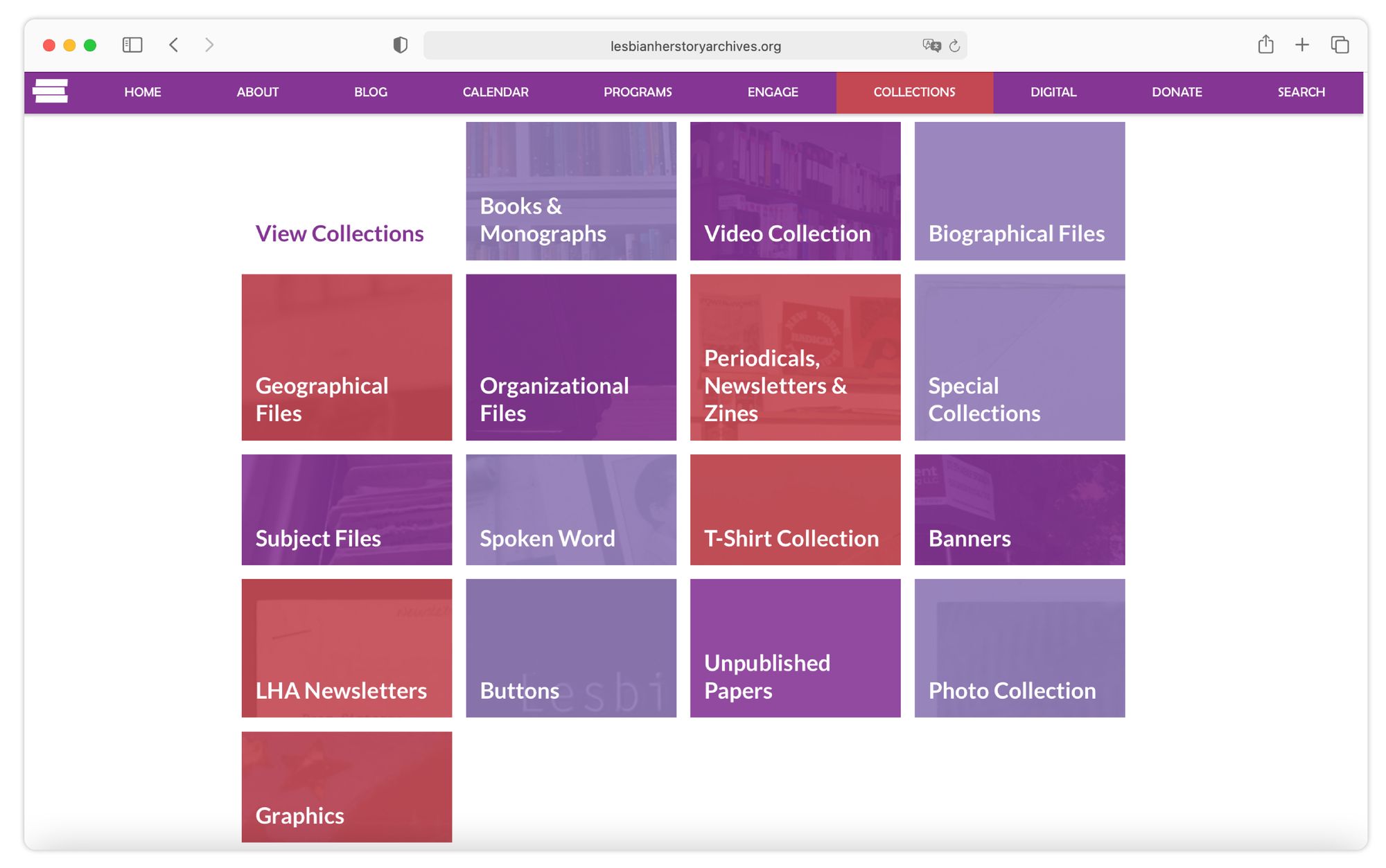

Like Sara Ahmed, scholar Amber Jamilla Musser thinks that we can learn a lot from lesbian feminism. At the conference “What happened to lesbian and gay studies?,” she defined “lesbian” not only as an identity and a strategy, but also as an explicitly political mode of living. In their 2020 book Information Activism, feminist researcher Cait McKinney investigates strategies and tactics used by lesbian feminists. As a nonbinary person committed to transfeminist practice, McKinney is also deeply attached to lesbian feminism. They stress the importance of archives like the Lesbian Herstory Archives (LHA), where they volunteered as part of their research. McKinney is interested in how lesbian feminists have, and continue to build, communication networks, databases, and digital archives that function as a foundation for their communities. McKinney argues in support of the feminist standpoint theory that we can learn much about oppressive systems from those who, because of their gender, sexuality and race, are pushed to the margins of society.

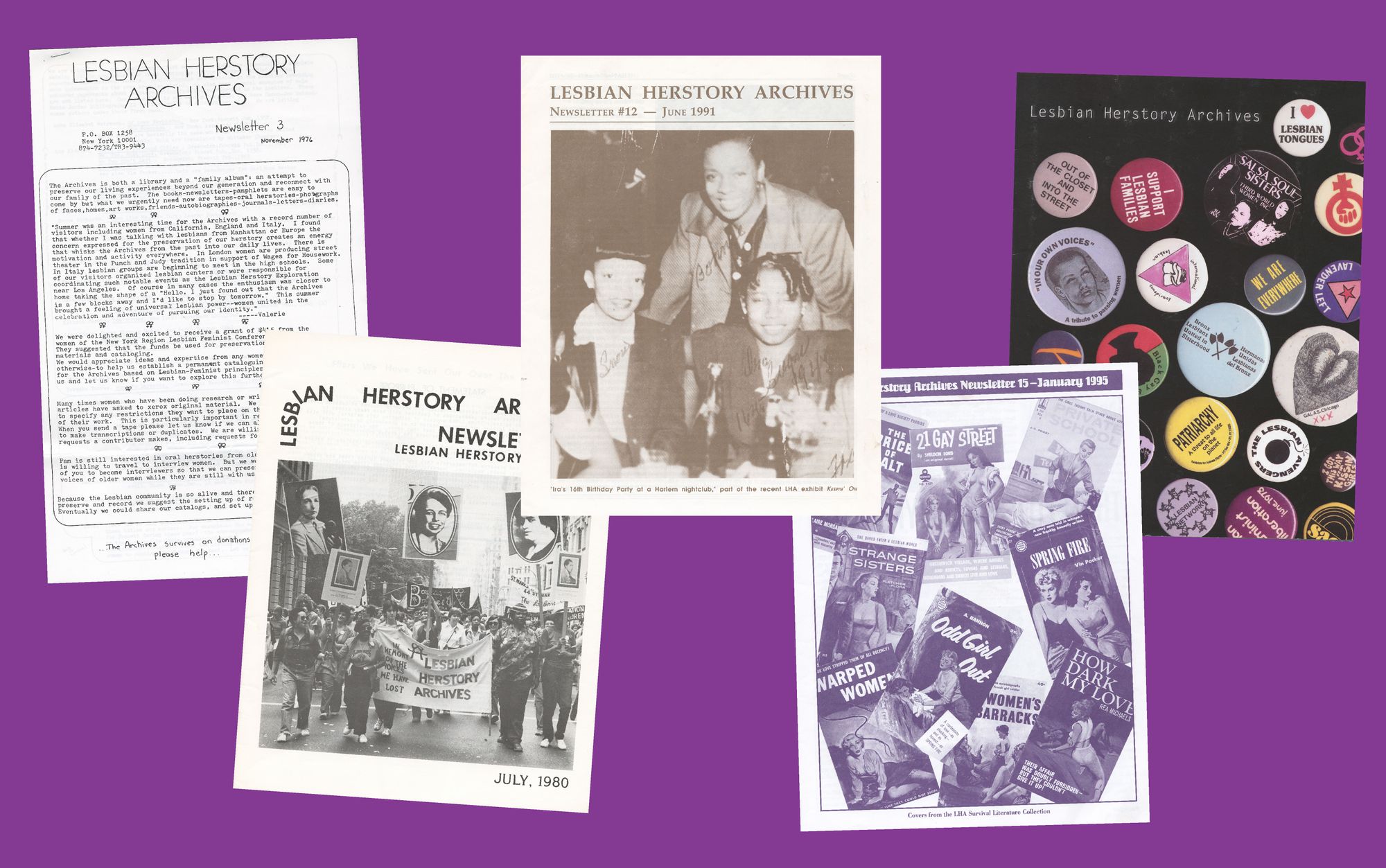

As we know from generations of feminist design researchers like Cheryl Buckley, knowledge about our own history and ancestors is crucial to guide us in the present, and to imagine alternative, more just futures. But what if we do not know our ancestors, because they have been rendered invisible? The LHA is one of the oldest LGBTQI+ archives. It was founded in 1974 in New York when a group of women involved in the Gay Academic Union (GAU) realized the importance of gathering and preserving records of Lesbian lives and activities, in order to be able to offer a past to future generations of lesbians. These women realized that they needed a space separate from the GAU to discuss sexism and other controversial topics. Joan Nestle and Deborah Edel became the founding site of the LHA, and Julia Stanley, Sahli Cavallaro and Pamela Oline were also involved in the creation of the concept. Today, the LHA holds the world’s largest collection of materials by and about lesbians and their communities.

Since 1974, many who identify as lesbian or have an attachment to this identity come to the archives (on location or online) to look for guidance. Following McKinney’s thinking, it becomes clear that even though the endeavor to establish a complete lesbian history is “undoubtedly utopian,” the idea of an alternative history and thereby also an alternative future still inspires a lot of FLINTA* persons (to borrow a term we use in German language that stands for women, lesbians, intersexual, non-binary, trans, and agender people as well as everyone who is not a cis-man). As they state: “It is precisely failure, loss, and impossibility that motivate the ongoing regeneration of feminism in the present.”

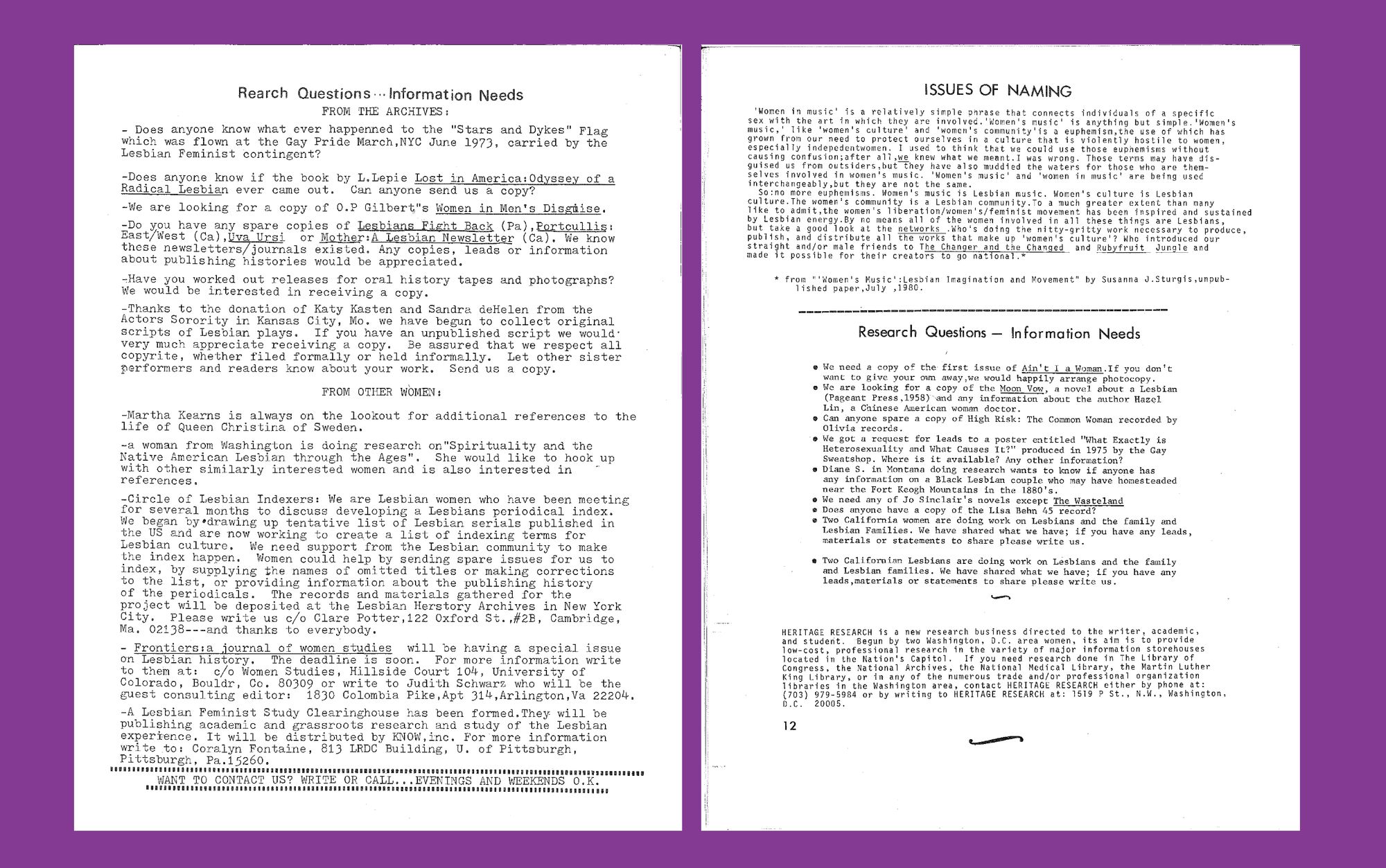

McKinney’s research is rooted in what Samantha Thrift calls “eventfulness”: the small, daily actions that are shaped by grand, utopian visions, and aim to sustain movements and communities over time to create conditions that can’t be found elsewhere. For example, McKinney looks into how newsletters helped to develop lesbian feminist networks and, eventually, even to bring archives like the LHA into existence. Against the backdrop of the Women in Print Movement and evolving ideas around networked communication, these newsletters were created, printed and published between the early 1970s and the mid-1990s. During this time, feminists made the most of new communications media and printing technologies like cheaper offset printing presses and copying machines, to which they now had access, with some even secretly printing lesbian materials at their workplace.

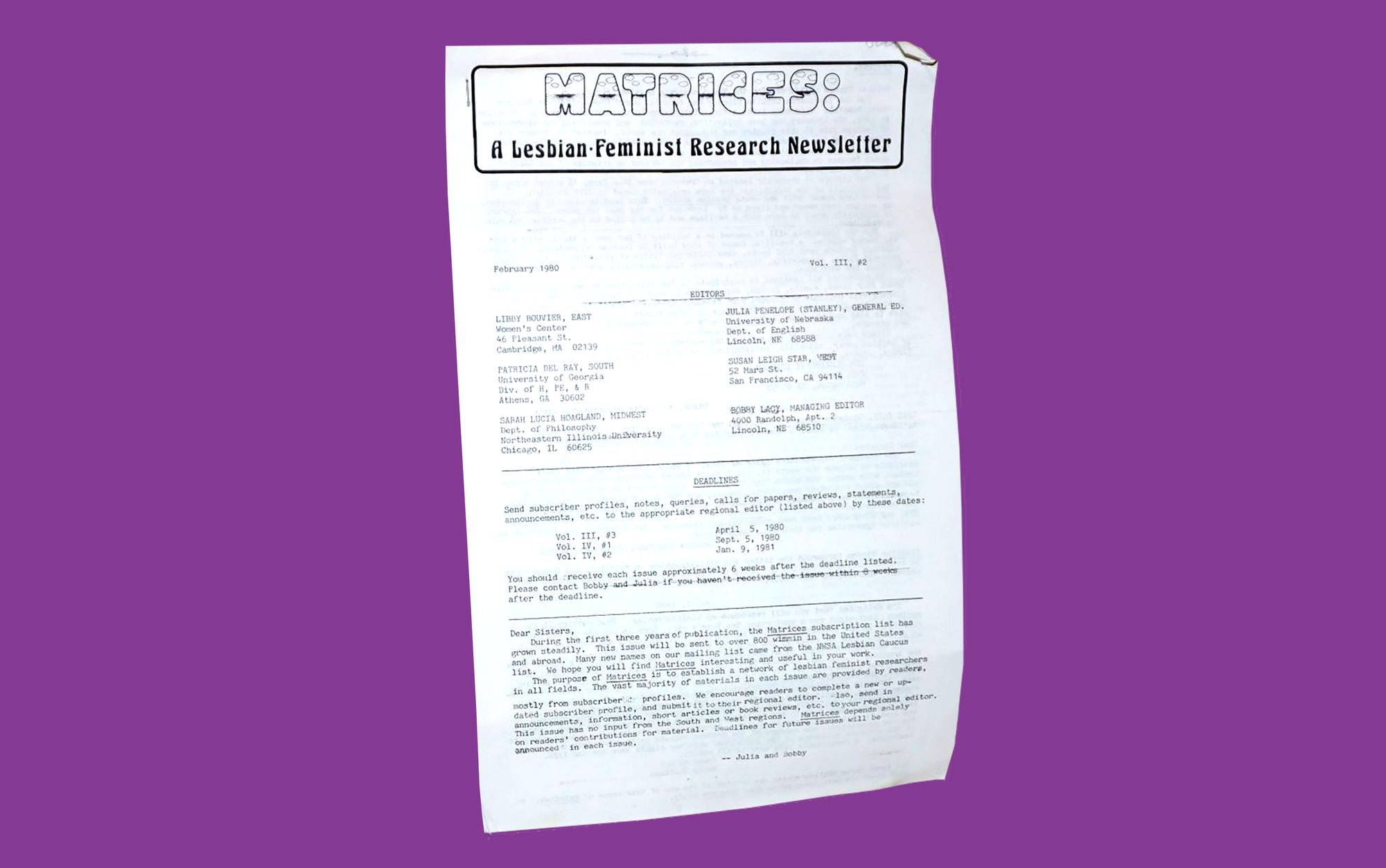

The newsletter Matrices: A Lesbian Feminist Research Newsletter was published from 1977 until 1996 to connect lesbian academics. Like many similar endeavors, its aim was to create a network for exchange and mutual support despite the challenge of long distances. Following a letter by Julia Penelope that she sent to academics, activists, and artists working on lesbian-feminist topics, Matrices was founded by her in collaboration with Libby Bouvier, Sarah Hoagland, JR Roberts, and Susan Leigh Star, who were all spread across the United States of America. Later, the network would become international. “Newsletters were a kind of connective tissue that made readers aware of the larger information infrastructure lesbian feminists were building,” McKinney writes. They published reviews, listings, and calendars that informed communities about new archives, books, or events. The “broader, social-justice oriented goal,” as she terms it, was “improving lesbian lives with information.”

According to McKinney, what was so fascinating about Matrices is the fact that it “transcended the limits of the centralized network model […] typically associated with a print publication or broadcast media, which center a single creator.” Each individual researcher or organization that received the publication could become a “node”—a starting point for new correspondence—because (with your consent), Matrices published your contact information, general research interests, and even specific questions or calls. As McKinney points out, this gave each reader the possibility to “continue their communication independently of the publication’s pages, forming a distributed model.”

The idea behind physical archives like the LHA was that they “would function as the ‘resource room’ and ‘cultural center’ ” (p. 56). The LHA had its own newsletter, which was published from 1975 until 2004. In comparison with Matrices, the Lesbian Herstory Archives Newsletter was more centralized, with the LHA as the network’s hub. In particular, early issues published in the 1970s were crucial in supporting the growth of the LHA. They featured an “Archives Needs” section, which outlines specific issues they were seeking for books and newsletters, as well as requests for skills such as translation, a much-needed resource among its existing volunteer base.

Alongside analyzing lesbian feminist newsletters, McKinney explores how lesbian feminist telephone hotlines gave their callers access to critical information and support that they could not find anywhere else. She also details how a group of lesbian-feminist information activists called Circle of Lesbian Indexers (1979–1986) improved access to already published materials by designing feminist indexing protocols. McKinney also discusses how the LHA and other lesbian feminist organizations have dealt with the topic of inclusion and exclusion over time. It is particularly painful to see how trans people have been—and are still today, by some organisations—excluded through certain definitions and practices. For example, guidelines at the switchboards of hotlines often lacked a clear definition of “woman,” and as a result, some volunteers refused to give information to transwomen callers. Some archives also misgendered trans women as well as trans men due to transphobia, lack of knowledge, and unclear definitions and guidelines. At the same time, it also becomes clear that many lesbian feminist communities have, eventually, learnt to face their own discriminating patterns and to deal with conflicts, no matter how uncomfortable they may be.

“It is particularly painful to see how trans people have been—and are still today, by some organisations—excluded through certain definitions and practices.”

In 2018, the LHA revised their “Statement of Principles,” and it now officially says: “The Archives collects material by and about all Lesbians, acknowledging changing concepts of Lesbian identities. All expressions of Lesbian identities, desires and practices are important, welcomed and included.” However, there is of course no end to addressing conflicts. I think we can learn much from “staying with the trouble,” as Donna Haraway says, and from those who stay open-minded and willing to also change their own convictions and patterns of thinking and acting in order to grow as individuals and as communities. I strongly agree with Sara Ahmed when she says that we have to create “spaces that are for women: and for women means, for those who are assigned or assign themselves as women.” As she suggests, “it is transfeminism today that most recalls the militant spirit of lesbian feminism in part because of the insistence that crafting a life is political work.”

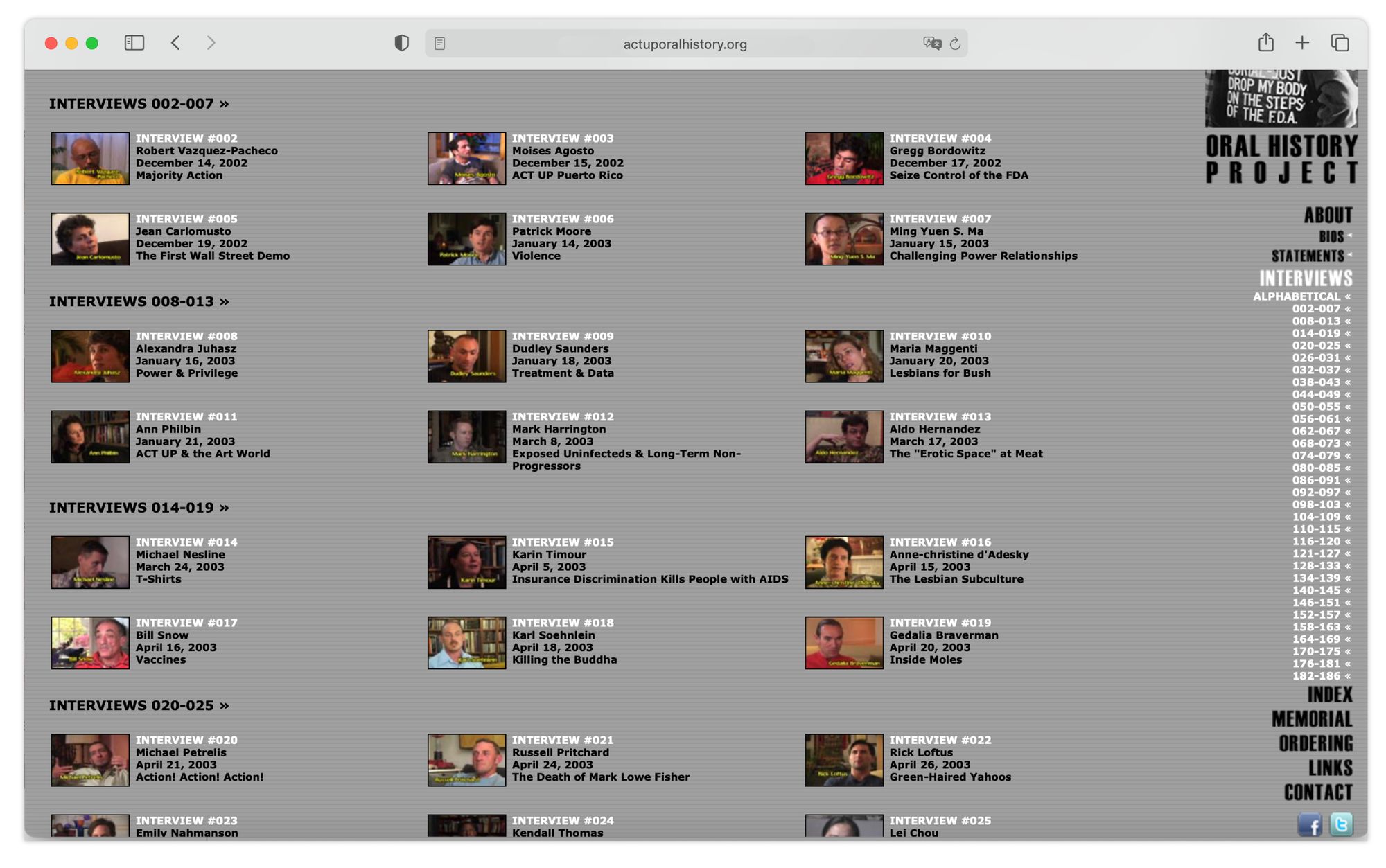

Inspiring strategies and tactics can also be found in the latest publication by lesbian writer and scholar Sarah Schulman Let the Record Show: A Political History of Act Up New York, 1987–1993, published earlier this year. On a recent episode of the podcast Outward, Schulman speaks about the AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power, or ACT UP New York, in which she has participated. Even though AIDS was often perceived as a “gay man’s disease,” many women, and among them many lesbians, were deeply committed to fighting it as well (and unfortunately got recurrently rendered invisible in historical accounts on ACT UP). As activist Alexis Danzig says in an interview with Vice, “Generally the lesbians in ACT UP came to the organization because of deep personal and professional friendships with gay men.” I propose to understand this solidarity with and care for their gay brothers as rooted in lesbian feminism, since it is so much informed by the lesbian experience of how crucial support networks are, especially when you leave heteropatriarchy that Ahmed describes “as an eleborate support system.”

Together with Jim Hubbard, Schulman initiated and coordinated the ACT UP Oral History Project, which functions like an archive and builds the foundation for her book. Like any political group, ACT UP had been influenced by other activists, among them the Black Power movement of the 1960s and its philosophy of direct action. For Schulman, “one of the most important lessons” is that ACT UP “did not use consensus at all.” She explains: “If you were doing direct action to end the AIDS crisis, you could do it. And if you wanted to get arrested on the Lower East Side doing illegal needle exchange and […] I thought that was terrible, I wouldn’t try to stop you from doing it—I just wouldn’t do it [myself].” There were always plenty of other possibilities that people could engage in instead, like disrupting mass at a church. This radical democracy and direct action were of course rooted in the fact that people in ACT UP were confronted with death on a daily basis—they or their loved ones were in huge and proximate danger to die any time, and most of them did. Trying to achieve consensus would have failed in this context. Schulman, however, goes further and wonders if consensus has actually ever been successfully applied in movements.

In her book, Schulman shows how “your strategy mirrors your social position.” She juxtaposes three examples to explain her point. Firstly, while some white male activists were able to relatively quickly get meetings with representatives of the pharmaceutical industry, it took women with HIV two years to even get a meeting—and “by the time they won, which took four years, most of [them] were dead.” Also, these women “had to do very messy strategies: they handcuffed themselves to leaders, they screamed at people in airports, they broke into offices.” Finally, as a third example, she mentions intravenous drug users whose actions were “[the messiest] it can get”: many overdosed, and “one guy stole $10,000 from the organization.” All of them had the same goal: they all wanted to end the AIDS crisis. However, because of their different positionalities, they also had different possibilities and different limitations. As Schulman says, “The more [marginally] you are positioned, it may take longer, and you have to be messier to win, but you can win no matter where you are.”

“If your possibilities for developing and applying certain strategies and tactics depend on where you stand, you have to first get an idea of your particular standpoint—and how you got there.”

If your possibilities for developing and applying certain strategies and tactics depend on where you stand, you have to first get an idea of your particular standpoint—and how you got there. As we saw earlier, ancestors and their wisdom can guide us. The material gathered here can only give small insights into what we can learn from our ancestors.

Lesbian feminist strategies that we can apply for our struggles in the design field include asking questions in order to identify differences that might be invisible at first, but may turn out to be crucial. Another strategy revolves around the creation and maintenance of supportive networks, because when we as FLINTA* center our lives around other FLINTA*, we leave the safety net of heteropatriarchy. This means we will never be able to fully rely on the state, society in general and relations to straight cis-men—whether with regard to professional development, financial security, or other aspects. Furthermore, decentralized networks and modes of production can be more sustainable and help to balance responsibility, workload and agency. We have also seen the importance of addressing conflicts and learning from those who are less privileged or differently marginalized than us. In addition, acknowledging a multiplicity of strategies is crucial, since your strategy mirrors your social, cultural and material position.

I think it is totally worth it to dig deeper to be able to apply what we find to our activism(s) in the design field, and to further develop our own strategies and tactics. In this, lesbian feminism can definitely support us.

Anja Neidhardt (she/her) works as a PhD student at Umeå Institute of Design and Umeå Centre of Gender Studies. Drawing inspiration from protest archives like the Lesbian Herstory Archives, she aims to imagine what alternative design museums could be like. Her research revolves around the question if (and how) alternative design museums that are based on feminist values might even be able to take part in creating a more just design discipline and therefore also more just futures.