As Iran enters yet another week of women-led protest fighting for liberation, justice and equality, we bring you a conversation between two expatriate feminist activists: Tehran-born and Jerusalem-based Orly Noy, and lawyer and human rights advocate Shirin Ebadi. This piece has been originally published in the independent, online, and nonprofit magazines Local Call and +972mag.

Countless hashtags have accompanied the flood of photos and videos coming out of the demonstrations raging in Iran during recent weeks. Chief among them is #mahsa_amini—the Persian name of a 22-year-old Kurdish woman (whose original Kurdish name is Jina/Zhina Amini), who was brutally killed by the regime’s “modesty police” after she was arrested for the crime of wearing “improper hijab” on Sept. 14th, which ignited this current wave of protests.

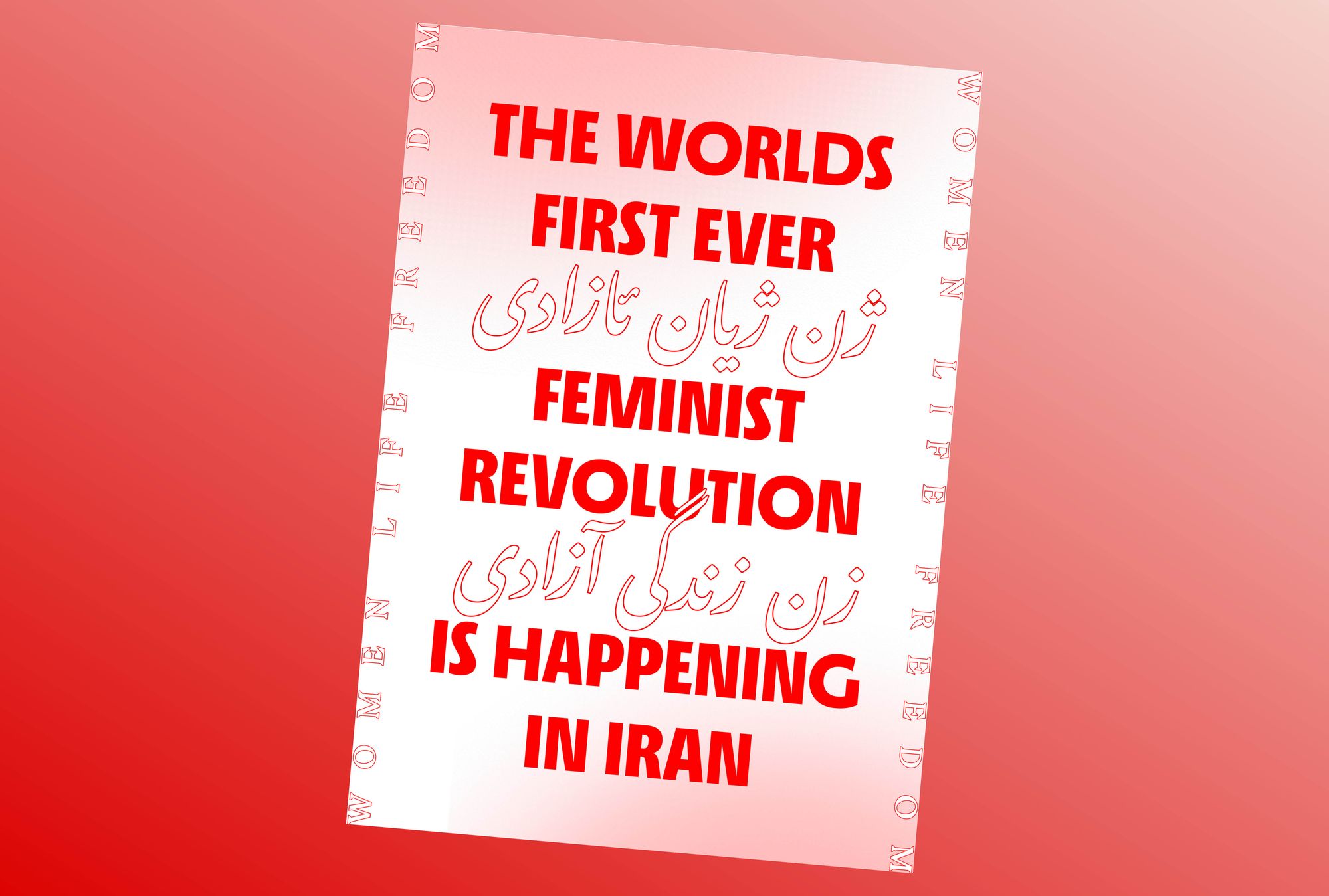

Particularly prominent among the other hashtags has been “woman, life, freedom” (“زن, زندگی, آزادی”), a slogan originally championed by Kurdish feminist movements and which has since become a popular mantra of the protests throughout Iran.

The direct link between women’s rights and the popular struggle for freedom is not new to Iran’s public discourse. In many ways, the attitude toward women’s rights—and their violation, in particular—has largely become the litmus test of the Islamic Republic since its inception in 1979. For this exact reason, the struggle of Iranian women is the most determined and courageous public struggle under the regime, drawing on the historical roots of women’s movements that arose in the country long before the Islamic Revolution.

The women’s struggle has produced exemplary figures who have become icons of fearlessness and resistance. These include the human rights lawyer and winner of the European Parliament’s Sakharov Prize for Freedom of Thought, Nasrin Sotoudeh, who has served long periods of imprisonment (including her current prison term of 5 years, which began in 2018) and even went on a hunger strike during one of her periods of incarceration; Neda Agha-Soltan, the young woman killed during the “Green Wave” protests in 2009, whose death photos became a symbol of the protests; and the journalist and human rights activist Narges Mohammadi, whose book White Torture addresses the regime’s policy of isolating female political prisoners in jails, where she also served considerable periods of incarceration.

All of these women, and many more, owe a huge debt to one of the pioneers of the feminist struggle in Iran after the Islamic Republic’s establishment: the 2003 Nobel Peace Prize winner Shirin Ebadi.

Until the 1979 revolution, Ebadi—who was one of the first female judges to be appointed in the country—served as president of the Tehran district court. After the revolution, the Islamic regime canceled the status of women as judges, and Ebadi turned to writing books on human rights in Iran, and working as a lawyer representing several prominent opponents of the regime. Her clients included Nasrin Sotoudeh, the writer Abbas Maroufi, and families of the regime’s victims such as Nation Party leader Dariush Forouhar, who was murdered by agents of the regime together with his wife, who also fought for women’s and children’s rights.

In 2003, Ebadi became the first Iranian and the first Muslim woman to win the Nobel Peace Prize. The award itself was later confiscated by the Iranian regime, and Ebadi left Iran for London, England in 2009, where she currently lives and still works for the democratization of Iran.

I sent Ebadi an interview request without much hope; an interview with an Israeli media outlet is no small thing, even for Iranian expatriates. To my surprise, she responded affirmatively within less than 24 hours.

On Sept. 30th, she opened our conversation with an apology and a hoarse voice—“Excuse me for the coughing; this is my fourth interview in a row today.” At the age of 75, Ebadi is closely following the developments in Iran, and diligently working to support the mass protests from exile. And she is convinced: this is the beginning of the end of the regime.

Orly Noy: When you see the photos and videos coming out of Iran right now, what do you feel?

Shirin Ebadi: It gives me a sense of pride that the young women and men of the homeland are standing in the battle so bravely, without fear; but also a sense of sorrow. More than 70 people have already been killed [Editor’s note: the death toll has since climbed to over 300, as at date of publication November 13th, 2022]. Just today [September 30th, 2022], in the city of Zahedan in the eastern province of Sistan and Baluchestan, police opened fire indiscriminately on the people. The videos coming out of there are very painful.

In recent years, we have witnessed several waves of protests in Iran on various issues, from workers’ rights to the cost of living. Do you think the current protests are fundamentally different from what came before?

Definitely, in several ways. Firstly, it includes all layers of society, from the young to the elderly. Secondly, unlike previous protests which were more specific—that is, everyone took to the streets to shout about the particular thing they lacked —this protest is political and the public is united behind one demand: the overthrow of the regime and the establishment of a secular democracy.

Thirdly, in the previous waves, the people used to gather in one place and the police would easily surround and suppress the protest. But now, the people have learnt, and they are demonstrating in every city, in many dispersed locations. This has succeeded in diluting the forces of repression.

The government does not have enough forces on the ground, so it is courting the favor of the Basij forces [a volunteer militia subordinate to the Islamic Revolutionary Guard], many of whom are under the age of 18. In photos and videos, you can see children with batons in hand, who are paid to beat the demonstrators. This is a case of child exploitation, and I filed a complaint about this with UNICEF, because similar to what occurred during the Iran-Iraq war (1980-1988), the Iranian government is using children in situations of war or violence.

“This time, people are fighting back, as is their right. This right is enshrined in both international human rights treaties and Iranian laws.”

Another unique aspect is that the protesters are showing courage and defending themselves. In the past, they would simply stand by as they were beaten or arrested, while the police themselves would break windows or set fire to a scooter and blame it on the protesters. But this time, people are fighting back, as is their right. This right is enshrined in both international human rights treaties and Iranian laws. It makes the forces of repression think twice. In some places, we saw that the power the public demonstrated was so great that it caused the forces to flee. They are afraid to confront the people.

All these points indicate that this is the beginning of the fall of the Islamic Republic.

In other words, these are not calls for reforming the regime, but to dismantle it?

Exactly. Because with the Islamic Republic’s constitution, no reform is a real possibility in Iran. The Iranian public knows that very well, and have understood that for years now. During the wave of protests five years ago [which started in December 2017 in the Khorasan district against price hikes, unemployment, and the internal politics of then-president Hassan Rouhani], people shouted the slogan “reformers, conservatives—the story is over.” From that moment on, that slogan became permanent in people’s voices. The people won’t be fooled by the description of “reformists” and we won’t be satisfied with less than the toppling of the regime.

There is a feeling that there are constantly-burning coals of resistance under the ash of oppression in Iran, which from time to time explode above the surface. That constant and brave resistance is led by women. In the photos we see today, women are taking off their hijabs in front of cameras and protesting the regime with their faces showing. It gives the impression that they defeated fear.

That is exactly it. Iranian women opposed the Islamic Republic from the first day after the revolution, because they lost all the rights they had previously achieved. This time they completely let go of fear and protected themselves in the face of the violence of the oppressive forces.

“They know that if women win, it would be the first step toward the democratization of Iran. I have no doubt that democracy in Iran will arrive through women.”

Alongside the feminist resistance, the issue of the compulsory hijab has been on the table of the Iranian public since the first day of the Islamic regime. You were among the first supporters of the campaign “A million signatures against compulsory hijab” in the early 2000s. Nowadays, with the revoking of this law in Saudi Arabia, Iran may be the only country in the world that still has such a law. How do you explain the hijab becoming such a fundamental issue for the Islamic Republic?

The regime sees the hijab as its flag, and they have said more than once that if they make any concessions on the hijab issue, then they will have to give people the rest of their rights. The public understands that well, and that’s why today both women and men are calling to cancel the forced hijab. They know that if women win, it would be the first step toward the democratization of Iran. I have no doubt that democracy in Iran will arrive through women, and that is why we are seeing mass participation in this protest.

As you mentioned, this protest has already claimed the lives of more than 70 people [Editor’s note: the death toll has since climbed to over 300, as at date of publication November 13th, 2022]. In your opinion, how far is the regime willing to go with its violence to suppress the protests?

Unfortunately, this regime has already proved more than once how violent it is. It always responded to the public with imprisonment and shooting. But this time, the number of protesters is huge, and the regime cannot imprison everyone. It will stop somewhere. According to unofficial information, quite a lot of the oppression’s forces rebelled or refused to participate, making various excuses not to show up to work. A lot of them would rather not clash with the public, because they know that if the public wins, they will pay for it personally. The regime is not in a good situation.

I would like to ask you about the day after the fall of the Islamic Republic. In conversations with Iranian friends, they talk a lot about the price of the crumbling of Iranian society after years of oppression and internal incitement. On the other hand, we see men protesting alongside women in the streets, and students from various universities announcing strikes in solidarity with women. Is Iranian society holding on to internal solidarity in order to establish a new future?

As we speak, the Iranian people are united because they want one thing: to topple the regime. What will happen after the regime falls? That depends on several factors. For example, what will be the price that the regime will take ahead of its downfall, and how many people will it kill? What will be the economic situation in Iran? It is all connected to the domestic and international situation.

“The West declared support for the Iranian people, but we do not want words—we want actions.”

We have also been witnessing a wave of protests across the world in solidarity with Iranian women. How do you see the role of the international community? Does the world need to get involved? If yes, how?

The West declared support for the Iranian people, but we do not want words—we want actions. Actions such as expelling Iranian ambassadors in protest of the regime’s violent oppression, or downgrading diplomatic ties from embassies to consulates, or withdrawing their envoys from Iran.

What about Iranians living abroad? Do they also have a role in the people’s fight?

Of course! After all, we are also Iranians—we left Iran for different reasons, but we are all the sons and daughters of the Iranian homeland. Thankfully, Iranians abroad worked exceptionally and effectively. We see them in protests worldwide, in Australia, Indonesia, Korea, Europe, the United States, and Canada. The benefit of those protests is grabbing the attention of citizens of different countries— meaning, they understand that something is happening, and they go to read about it. Local media is also reporting on the protests, and it helps spread the news from Iran to the world.

There is one more thing that Iranians living abroad can do: translate the reports and videos coming out of Iran into your local language, and send them to media outlets and TV stations. Spread them at your workplace, to friends, to neighbors—that way, you can let the world know about the atrocities against the Iranian people.

What price are you paying for your years-long fight? There were threats against your life more than once, and to pressure you, your sister was even once detained in Iran. Are you still under threat?

Yes, the threats never stop. There’s a documentary about my life which was screened this year at the Venice Film Festival, called Until We Are Free. The director, the festival, and I all received threats warning us not to screen the film. Of course, we did not comply. We are not afraid of them, despite the fact that the movie made the regime officials lose their minds.

My last question is not connected to Iran but to our reality here in Israel-Palestine. Several years ago, you supported the call of students at the University of California in the U.S.A., asking it to withdraw its investments in occupied Palestinian territories. It was an unprecedented move, given the general avoidance of Iranian human rights activists and regime opposers around the oppression of Palestinians. Can you explain that?

The truth is that in Iran there is always something happening daily, and sadly there isn’t a good flow of information in the country. We Iranians are so wrapped up in our own troubles that we forget what is happening in the rest of the world. But I’m a human rights activist, and I oppose violations of human rights everywhere in the world. Just as I’m terrified and affected by the Holocaust and the crimes done to many people because of their identity, for these same exact reasons I’m terrified and saddened that innocent people are losing their homes and becoming refugees. It is not connected to religious identity or nationality, because human rights are an international matter, and we have to respect them in every corner of the world.

Orly Noy (she/her) is an editor at Local Call, a political activist, and a translator of Farsi poetry and prose. She is the Chair of the B’tselem executive board and an activist with the Balad political party. Her writing explores the lines that intersect and define her identity as Mizrahi, a female leftist, and as a woman.

Shirin Ebadi (she/her) is an Iranian activist, public intellectual, lawyer and a former judge. In 2003 she was awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace for her human rights work, which was later on confiscated by the Iranian regime. Since 2009 she has lived in London continuing her activism from exile.

Title image: Poster by Parasto Backman.

This poster goes out to all the brave people in the region of Iran who lead this revolution.

Parasto Backman (she/her) is a graphic designer and educator. She works with projects across art, culture and business and her commitment lies particularly in highlighting design as a complex and versatile practice with great opportunities and responsibilities in a wider context.

A first version of this article appeared in Hebrew on Local Call and then in English on +972mag. This current version was slightly edited for clarity. +972mag is run by Palestinian and Israeli activist journalists. It amplifies voices marginalized in mainstream reporting from the region, centering communities opposing apartheid and occupation.