Trigger warning: Before you start reading, please note that there are graphic descriptions of police violence in this text.

I had just finished reading a chapter from Robin D.G. Kelley’s Freedom Dreams: The Black Radical Imagination to my dad. His head jerked awake as I came to a stop in the middle of a paragraph. He had dozed off to the sounds of Ramon Durem’s “Hipping the Hip,” and came to twenty pages later, as I read aloud: “W.E.B. Du Bois’s sentiment that ‘capitalism cannot reform itself, a system that enslaves you cannot free you’”

“Dad, what do you think about prison abolition?” I asked.

This 72-year-old Black man, a direct descendent of enslaved Africans, a man who grew up sharecropping in segregated South Georgia, cannot fathom the concept of abolishing police and prisons.

Maybe it’s naïve of me to think he would. He trusts that reform and better oversight or accountability will resolve the “problem” with policing and incarceration. To him, neither institution is the problem. The irony of our lineage and his conclusion confounds me; but, it’s familiar, it’s the norm. How can we understand that abolition was the only way out of slavery but not see, too, that it’s the only way to freedom, today? What will it require to unsettle our trust in a set of institutions that never served us?

“We struggle to imagine a world without police, prisons, or capitalism, myself included. We’re beholden to a crisis of imagination which is, in many ways, symptomatic of “disaster capitalism”

He stalked off to get dressed for his daily walk through the trails near our house. He came back a few minutes later, decked out for his daily exercise. “While you’re off traipsing through the backwoods of Southern Maryland,” I started, heavy on the sarcasm, “...where I’m sure many a maroon fled toward safety, why don’t you imagine what would’ve happened if they’d just tried to reform slavery? What if they’d just said ‘We need some more oversight on the slaveowners and overseers, maybe cut down on some of the raping and family separation, and give them a couple days off a year.’”

I laughed to myself. He stared blankly for a minute before turning through the sliding glass doors and heading off to the trails.

Manufactured Disasters and Disasters of Manufacturing

We struggle to imagine a world without police, prisons, or capitalism, myself included. We’re beholden to a crisis of imagination which is, in many ways, symptomatic of the “disaster capitalism” of which Naomi Klein writes: Catastrophic (often humanmade) moments in which “we are hurled further apart, when we lurch into a radically segregated future where some of us will fall off the map and others ascend to a parallel privatized state.”

Detroit, Michigan—where I live—is a city defined by manufactured disasters and disasters of manufacturing: The abandonment by the auto industry and the subsequent mismanagement by the apparatus of the City itself decades later have unmistakably shaped life in Detroit. The fallout of these crises left behind thousands of stranded workers, literal industrial and residential ruin, structural decay, streets in disrepair, gutted houses and gutted homes and gutted neighborhoods, disinvestment in people and place, a tragedy and a “beautiful wasteland” as described by Rebecca Kinney in Beautiful Wasteland: The Rise of Detroit as a Post-Industrial Frontier. The “New Detroit”—the shiny, saccharine, “revitalized” downtown—is the parallel privatized state that Klein referenced. It is the prize of catastrophe awarded those who stand to benefit from this radically segregated future.

“Speculation has become the purview, exclusively, of those who command enough capital to make new worlds appear out of ruins or thin air.”

We are convinced en masse that the capacity to “speculate,” to construct futures, is the exclusive domain of those who’ve mastered speculation in a neoliberal sense. Only through the specialized techniques of contrived calculations, computational sciences, and statistics can we model and predict the future. In The Future as Cultural Fact, Arjun Appadurai writes that the future has “been more or less completely handed over to economics.” Speculation has become the purview, exclusively, of those who command enough capital to make new worlds appear out of ruins or thin air. “To most ordinary people—and certainly to those who lead lives in conditions of poverty, exclusion, displacement, violence, and repression—the future often presents itself as a luxury, a nightmare, a doubt, or a shrinking possibility.”

To borrow from Appadurai, what’s needed, in a space where the capacity to speculate is denied, is a politics of hope which depends on our capacity to “convert uncertainty into risk” by—in my estimation—collaborating to imagine a world that the calculations of neoliberal financial speculation tells us is impossible.

What if we could imagine a world without police and prisons and capitalism? Not just think, talk, or write about it, but truly see, feel, hold, and sit in it?

Making Room

I’m partway through imagining and materializing a version of an abolitionist world through the lens of a living room in Detroit. (I feel much safer writing about this work than making it.)

Opening on October 8, 2021, at Red Bull Arts Gallery in Detroit, MI, “Making Room” is an installation of a living room situated across time(s) in a single space gradually inching toward abolition. It is a provocation, not a vision. The space makes room for critical conversations around what stands between us and abolition and what it might take to manifest a world without police and prisons.

“The artifacts that populate our homes express, articulate, embody, and reflect the social relations and systems that govern our lives outside of them. They contain histories and forecast futures[...] They tell stories about who we were, where we came from, the worlds that shape us, the rules we follow and break, the environments we inherit, the ways we survive, the worlds we presently inhabit, the things we fear and protect, and the worlds we hope to shape.”

That this imagined world takes place in a living room is an acknowledgment that our homes are microcosms of our wider worlds. The artifacts that populate our homes express, articulate, embody, and reflect the social relations and systems that govern our lives outside of them. They contain histories and forecast futures: The bills that pile up on our tabletops; the artwork that decorates our walls; the TV shows we stream; the songs we listen to; the chatter we hear from the street; the heirlooms we cherish and the ones that collect dust; the views we glimpse from our windows. They tell stories about who we were, where we came from, the worlds that shape us, the rules we follow and break, the environments we inherit, the ways we survive, the worlds we presently inhabit, the things we fear and protect, and the worlds we hope to shape.

I’m terrified by the certainty I feel obligated to convey in this room but can’t grasp in my own imagination. I’m afraid of the pressure, the inherent certainty embedded in an idea once rendered into an object that we can hold onto, turn over, toss around, believe in, and dispute. I also know that this perceived certainty—meant to be taken as evidence of the possibility of an altered reality, not a prediction—breeds a sense of believability that I urgently need to construct because nothing about abolition feels certain, beyond the fact that we desperately need it.

We talk about, write about, and practice abolition today, but rarely do we sit in a familiar space defined by abolition: Defined by the absence of law enforcement and cages and the presence of the infrastructures that support safety and belonging and transformation in every dimension of our lives.

For many of us, the living room is relatable, knowable, and malleable as an archetype of domestic space. We can situate and see ourselves in it, navigate its terrain, decipher its decor, make guesses about the family whose living goes on there, regardless of when or where it sits. Some of us call it a “family room,” instead. Whether we invite guests into it, entertain in it, make messes in it, put our cultures and families on display in it, encase its contents in protective glass or plastic, these are spaces that hold evidence of our worlds in ways that incrementally reveal what matters to us and how we live beyond those walls.

“While police may protect the homes of the wealthy, middle class, and gentrifiers, for Black, immigrant, working class, and poor families, too often the home is yet another landscape into which the carceral state permeates with little regard for its walls or locks or inhabitants.”

We often talk about home as a safe haven. But, home isn’t inherently safe from harm. For some, first of all, home is a place where harm is perpetrated by family or friends. For others, the state—the police, their weapons, the force of incarceration, child protective services—cross the threshold as if none exists at all. Anjanette Young scrambled to shield her body when nine Chicago police officers barged into the wrong apartment and handcuffed her naked in her living room. Botham Jean, who felt safe enough at home to leave his door unlocked, was murdered by an off duty Dallas police officer who barged into his front door thinking it was hers. Breonna Taylor awoke from her bed and took her last breaths to a barrage of bullets from the Louisville police department. Aiyana Stanley-Jones, a seven year old girl asleep in Detroit, was murdered by police officers who raided her home in the middle of the night with a reality TV show crew filming the entire encounter.

In light of electronic monitoring, too, homes are quickly transformed into holding cells, an integral extension of the ever-expanding prison system. Homes are fraught spaces where safety isn’t guaranteed, where the safety of its inhabitants is regularly violated in the name of “safety,” as defined by police. While police may protect the homes of the wealthy, middle class, and gentrifiers, for Black, immigrant, working class, and poor families, too often the home is yet another landscape into which the carceral state permeates with little regard for its walls or locks or inhabitants.

For these reasons and more, homes in overpoliced, disinvested, ghettoized neighborhoods like many across Detroit become part of the “carceral continuum” whether its residents like it or not. This continuum, as employed by Loic Waquant, expresses the range of many “peculiar institutions” devised, he argues, to “contain, confine, and control” Black U.S. citizens. Because of its place in this continuum, the home as a site of carcerality seems a fitting location from which to reimagine a world without carceral institutions.

How homes come to sit along the “carceral continuum” is, at least in part, a product of the neoliberal speculation of which Appadurai warned us in The Future as Cultural Fact. Detroit is shaped and reshaped by the “valorization of real estate as a central engine of urban revitalization strategies and their attendant displacement of poor, mostly black residents,” as Brett Story explains in Prison Land: Mapping Carceral Power across Neoliberal America.

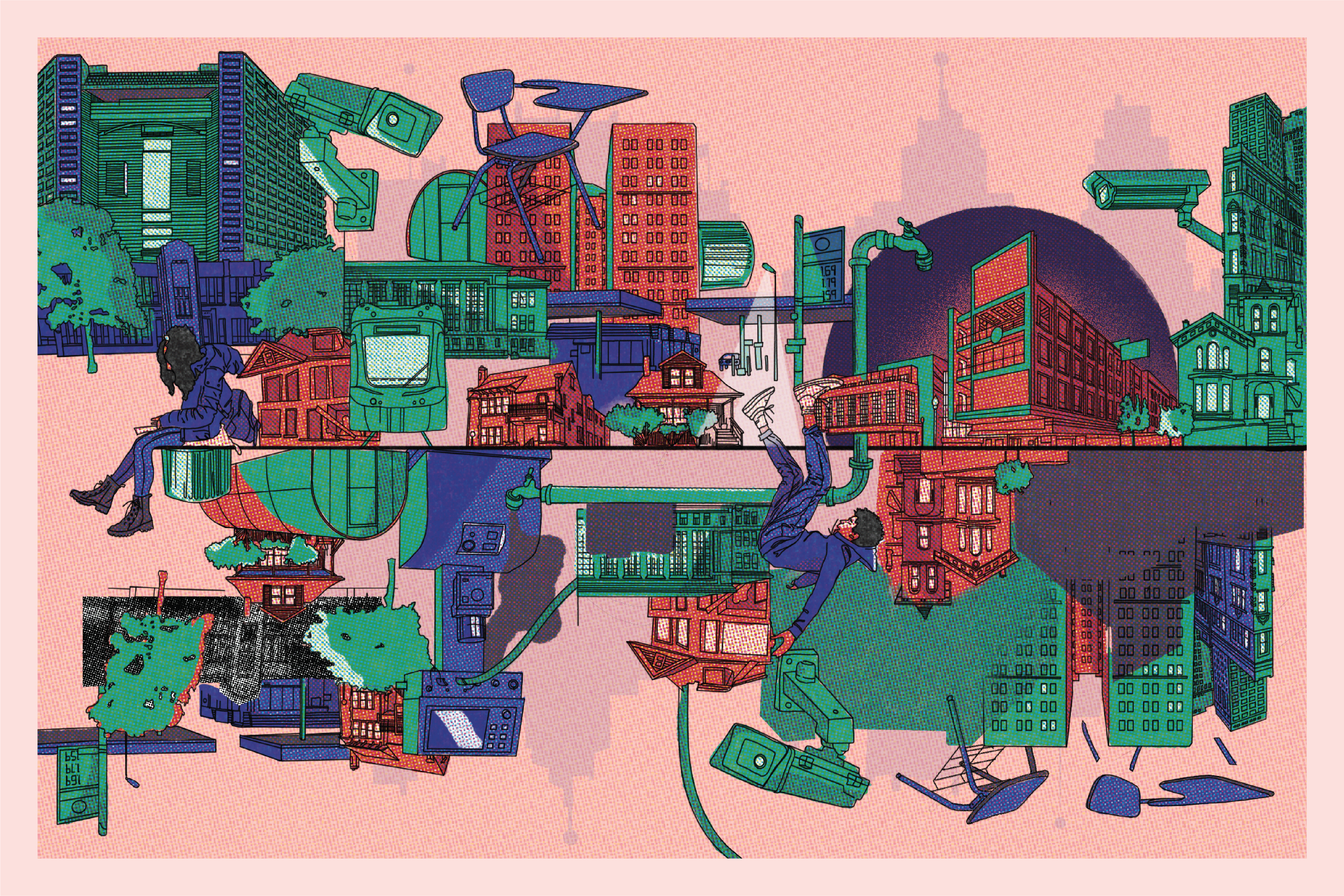

Story articulates the disturbing but predictable relations between policing, the privatization of public resources like water, and the securitization of real estate markets. They are inextricably tied in this city: In downtown Detroit—the gentrifying urban core—a vast surveillance infrastructure and private security force in coordination with the Detroit Police Department protects billionaire Dan Gilbert’s investments and cracks down on quality-of-life offenses. These are the “crimes” we commit in the course of trying to stay alive, like sleeping outside or in cars. They are rendered criminal in order to make way for the elite consumers needed to sustain downtown’s capitalist playground.

In outlying neighborhoods, broken windows policing and privatization of public goods lead to water shut offs for non-payment. Residents are under constant surveillance through Project Green Light, strategically placed security cameras on private businesses across the city with a direct line to the police department. Raids in apartment complexes lead to carting residents off to prison, clearing the way, again, for so-called “revitalization.” At the root of these techniques for clearing land for its newer, wealthier occupants is the apparatus of real estate speculation: Buying property to resell it at a higher price at some point in the future. The value of this “flip” is made possible in large part by the ways in which global financial markets transform housing into a vehicle for investment rather than a social good. These are neoliberal acts of speculation that render homes carceral spaces. As a consequence, many domestic spaces in Detroit come to represent the ways in which neighborhoods have been “divested of water, amenities, schools, and jobs and then cast as dangerous enclaves requiring massive police repression.”

“The dispossessions that make way for displacement aren’t accidents, either: They’re designed.”

Contemplating the living room as a container for an abolitionist imagination acknowledges the creeping scope of carcerality in this city and the insidious ways in which carcerality permeates through neighborhoods and households and walls. Through the lens of a home, we can begin to understand that carcerality is a set of social relations that appear all around us and—I hope—reimagine a different set of social relations that might initiate and sustain ongoing conversations toward liberation.

The dispossessions that make way for displacement aren’t accidents, either: They’re designed. The abandonment narrative driven by very real disinvestment in Detroit’s neighborhoods—the prevailing story of a “post-apocalyptic” city overtaken by abandonment and vacancy—directly fuels real estate speculation and redevelopment, and the state is more than complicit.

“The edifice of the prison and the implements of policing systems are, themselves, artifacts of design, too. The social and spatial relations produced by capitalism that underlie the supposed necessity of policing, are also designed”

The edifice of the prison and the implements of policing systems are, themselves, artifacts of design, too. The social and spatial relations produced by capitalism that underlie the supposed necessity of policing, are also designed: Intentful, deliberate decision-making and organizing of materials and technologies and people. Not to mention the technologies, buildings, apps, and equipment in which designers are conscripted to facilitate dispossession through surveillance, real estate speculation, neighborhood “revitalization” projects, and the aesthetics of gentrification. Power and the social relations produced by capitalism are thus embedded into these structures, the spaces they occupy, and the traces of their operations.

The valorization of real estate is a product and necessity of capitalism. Capitalism requires a permanent reservoir of disempowered, available, expendable labor. Policing helps to create that pool of vulnerable workers by criminalizing quality-of-life crimes, protecting wealth and property, and locking away non-compliant laborers in prisons. These are not incidental entanglements, either, they are integral to how it all works.

These are not systems that can be gently reformed.

I have to wonder how different our capacity to imagine must have been during the movement to abolish slavery. How did we imagine differently in a time without the internet and the immediacy of ideas exchanged across the world? This capacity to communicate, too, is a thing that’s shaped heavily by design. The technologies that enable us to exchange, to express our imaginations, and to render imagined ideas material, are products—in the last two-hundred years, at least—of design. Yet, are we somehow more entrenched today in spite of having more access to possibility, imagined futures, and radical ideas than before? Is it even possible to compare?

“The technologies that enable us to exchange, to express our imaginations, and to render imagined ideas material, are products—in the last two-hundred years, at least—of design.”

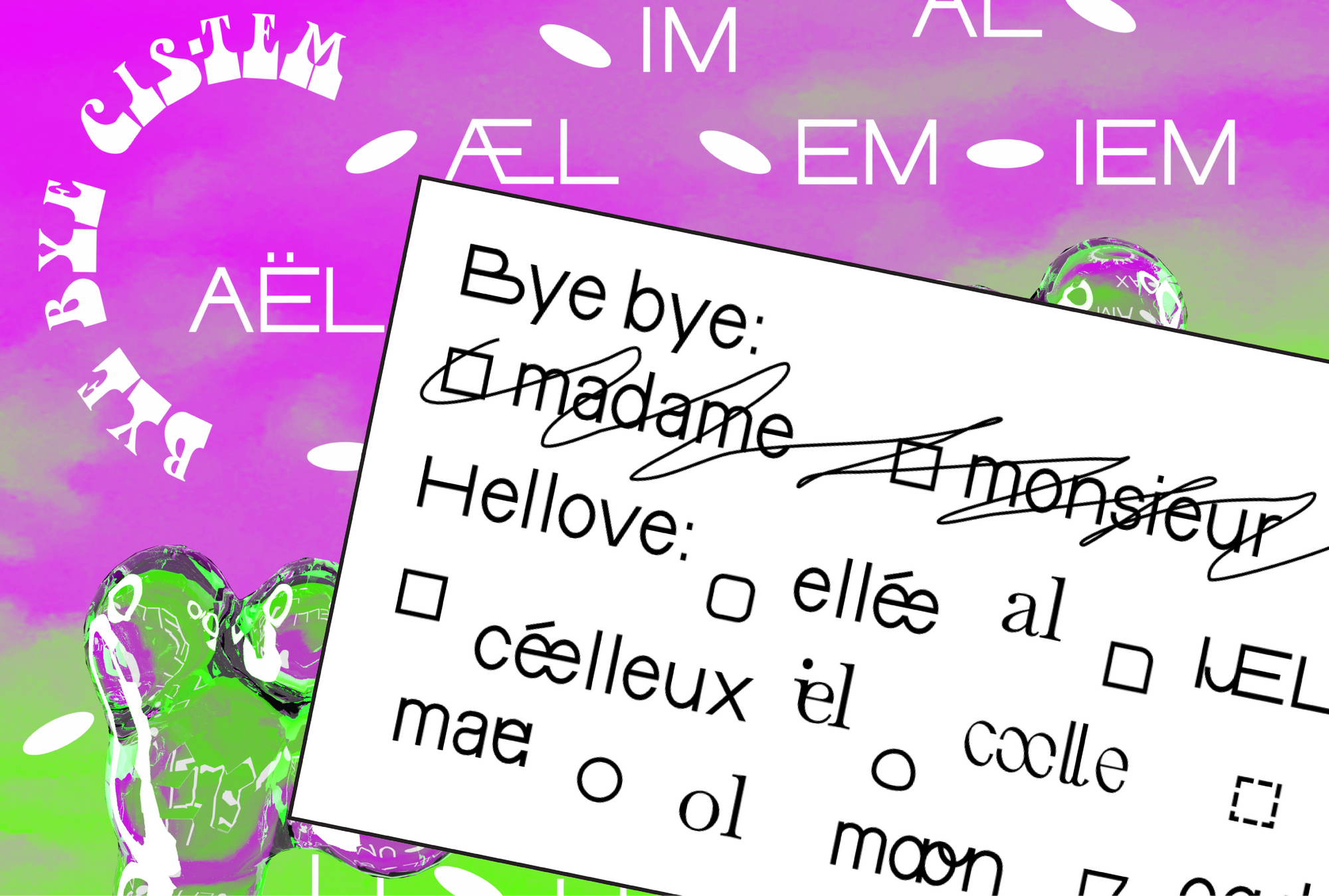

Today, our imaginations are constrained by the conundrum of an artificially produced scarcity of choice: The narrative of policing today, as presented by those who would maintain the status quo, immobilizes our imaginations and leaves us stagnant, at a state of impasse. It presents us with an impossible choice—a non-choice—between two unappealing outcomes.

Our options are framed as a completely lawless world, an anarchic state of chaos, rampant crime and violence, or a world in which we police each other so harshly that police operate with an unrestrained, state-sanctioned license to kill. It’s the choice between submitting to surveillance by the state and submitting to surveillance by corporations invested in protecting wealth and property over people’s lives. We are told and taught and compelled to believe that the only way to ensure safety—a very real concern at the root of skepticism about the feasibility abolition—is through force, coercion, and control by the state.

As Mariame Kaba describes on Prentis Hemphill’s Finding Our Way podcast, we derive pleasure from punishing those who have harmed us, revenge is satiating, and the “safety” produced through the prison industrial complex is an illusion. The bounds of our collective imagination are suffocated by our investment in the status quo, in the pleasure found in punishment, and by the propaganda funneled our way about policing and criminality and safety. Plenty of progressives lose faith in the promise of abolition worrying over who will keep us safe, if not the police, and where we’ll put the criminals, rapists, and murderers if not in prison. Abolition seeks to eliminate the conditions that enable the violences we perpetrate against one another interpersonally and through punitive social institutions like prisons. It demands that we redefine safety altogether. It requires that we keep ourselves safe.

Collapsing Timescapes

On one of the first warm weekends this past May, I sat outside with friends in downtown Detroit’s Capitol Park eating carry-out Thai food from a restaurant nearby.

The first time I came to this park was four or so years ago, about two years before I moved to the city. On this initial visit, I trailed behind the group of students I was teaching at the time, taking photos for posterity, and listening to Jamon Jordan of Black Scroll Network recount the history of the Underground Railroad—a feat he does entirely from memory—while we followed him dutifully around Dan Gilbert’s shimmering downtown Detroit.

On this night in May, I ate my pad see ew on a different park bench in the same park where I had learned about Finney Barn—the site of an earlier abolitionist movement—on that tour with Jamon a few years prior. As we ate, I chewed on the dissonance of it all. We were surrounded by the markers of an abolitionist history, of absconding, marronage, fugitivity and flight, displacement, and the promise of freedom. On top of those markers, and in front of them in time, sit other markers of a sparkling but sinister present in desperate need of abolition. A cosmetic surgery clinic faces a litany of high-end eateries and a building filled with luxury apartments. Those apartments once housed low-income Black seniors, sent into flight by eviction to make way for people with capital. Luxury looms over and around and in front of us.

The dissonance is like a hollow ringing in my ears, a tinnitus through time. It’s amplified, perhaps, by the fact that this is the first time I’ve ventured out downtown since the COVID-19 pandemic killed vastly disproportionate numbers of Black Detroiters. The pandemic, it should be noted, is yet another crisis manufactured by a neoliberal imperative to keep the economy going in spite of scientists and public health officials demanding a substantial shutdown. From where we sit, you can see and feel the surveillance cameras and security guards, the police presence, the edifice and the social relations produced by real estate capital, and the erasure of those inimical to the elite downtown referenced when we hear about a “revitalized” Detroit.

It makes my skin crawl. I have a visceral reaction to it. I want to go home, to stay inside, to not see it. To be fair, it’s not contained to downtown; it’s just so much louder here.

“Where the fuck are we?” I wondered, silently. “When are we?” is probably a better question to ask.

I’m struck by the precarity of building a “new” Detroit atop the so-called ruins of its predecessors, many of whom, by the way, are still here.

I lived in Mexico City for a while in 2018. As I sat in Detroit’s Capitol Park dissociating from the buzz around me, I was reminded of the groundwork beneath Mexico City. It sits atop the ruins of Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital city besieged by colonial war and disease that came with the settlers. As a consequence, the foundation of Mexico City is, quite literally, sinking. The physical infrastructure of the entire city today is precarious because of how it came to be. After the massacre, the Spaniards destroyed what remained of Tenochtitlan’s infrastructure, drained the lake on which the island-city once sat, and got to work constructing their new empire. Today, as the soil and clay that once sat beneath Tenochtitlan compacts, Mexico City drops another foot and a half per year. The physical infrastructure of the city we know today is compromised, at least in part, because of how it came to be, how it was founded, and who was erased to bring it to life. Major earthquakes, natural disasters, have rocked the city throughout time. The earthquake in 1985 and the one that hit the same day 32 years later both unmoored the city’s perilous physical foundation. The destruction was amplified by the disaster of colonialism that preceded it. I know, too, that many of the same social relations predicated on the capitalist speculation and attendant over-policing and surveillance that shape Detroit also shape Mexico City today.

I can’t help but see a parallel precarity here in Detroit, metaphorically speaking. We share with Mexico City, no doubt, a pattern of colonial, genocidal destruction that preceded the foundation of these major metropolitan areas. But, it’s also analogous to a more recent cycle of erasure: The construction of the “New Detroit” atop the Detroit that’s been here “in ruin" for the better part of a century.

The real estate speculation that produced the downtown Detroit that makes my skin crawl concerns futures and, it would follow, concerns time. Real estate speculation produces blight and disinvestment, then criminalizes both blight and people’s attempts to survive in light of that disinvestment, dispossesses them of the very things—home and neighborhood—that stand between them and obliteration, and then erases them and calls it the “rebirth of a city.” The machinations of this cycle play with the levers and perceptions of time: Which came first: The disinvestment or the “crime”? The over-policing of said “crime”? The dispossession? The chicken? Or the egg?

This speculation disorients us in time and on purpose. It obscures the precise moments in time we can blame for people’s erasure and enables those who would manipulate that obfuscation to convince us that the onus lies on residents for being “criminals,” for not evolving, for not earning enough to survive, for not buying into or being able to master the capitalist racket.

Detroit is the nation’s largest majority Black city, deemed either “behind the times” or a phoenix rising from the ashes of a protracted downfall. Time, here, is fraught. The Black experience(s) more broadly in the United States cannot easily be extracted from how we are collectively situated in time, either: They are shaped simultaneously by the weight of past and present oppressions and the precarity of our futures. Black people in the United States sit in this liminal space, bound by the histories that brought us here while crafting our futures in spite of the perilous positioning manufactured to make our lives less livable. White supremacy would have us believe that Black people are “behind the times” economically, socially, and otherwise; time shapes constructions of race and Blackness; our time is literally worth less than others’ on the labor market; time is an instrument of carceral punishment; and the time for justice is never now.

“Design is at best complicit and at worst a key facilitator of the future-facing real estate speculation that erases, subdues, and makes Detroit palatable and decipherable as a frontierland.”

I’m troubled by how to relate to time in the context of this imagined living room for “Making Room.” Is what I’m making a future or a history? Both? Neither?

When are we, again?

This and the uncertainty and the weight of it all are what scares me as I make. I worry, repeatedly, that employing design—a “master’s” tool—and speculation—another favorite tool of theirs—to construct this world is misplaced or naïve or both.

Design is at best complicit and at worst a key facilitator of the future-facing real estate speculation that erases, subdues, and makes Detroit palatable and decipherable as a frontierland. Design renders the city a land to be settled and made anew, a land with a future devoid of its past and present residents. My hope is that design can—by the same token—broaden our imaginations and make “tangible, relatable and specific” the possibility of an abolitionist world.

In the first month of making this work, I’ve already found that my reliance on design discourse and its tools leads me to reinscribe the institutions of today—whether knowingly or unknowingly—into this imagined world, home, and its contents. But, as Anab Jain reflects on exploring the possibilities of futures in the thick of the COVID-19 crisis, “the tools for navigating precarity and crisis and unknown futures will not be the tools we have used to maintain the certainty of progress, or the tools we have used for the pursuit of novel futures.” Maybe, then, the key is to abandon the possibility of certainty: To make multiple futures; to make multiple histories; to reimagine the present; and to contest them all in this “living” room in the name of constructing a liberated home that is wholly different from the master’s house we inhabit now.

Or perhaps, as Minna Salami writes in Sensuous Knowledge: A Black Feminist Approach for Everyone, if this living room enables us to “see reality clearly, wholly, with all our faculties,” it can help do the work of dis-mantling the master’s house by constructing this imagined home shaped by “poetry, playfulness, Eros, borderlessness, conscientiousness, dialogue, intuition, soulfulness, stillness, warmth, passion, beauty, compassions, mystery, wisdom, honesty, femininity, interiority, sensuousness, ogbon-inu.”

If I strip the rest away, the point of this living room is to change, or at least challenge, the course of our present and future by imagining an alternative telling of those moments in time. The point is to curate a sort of archaeological excavation—an unearthing of a past—of a domestic space that helps us see the possibilities for freedom produced by abolition. The point is to see what new questions and possibilities we can raise, open, debate, and refine by encountering these artifacts and this space. The point is for this room to inspire recurring, divergent, recursive, living reflections and provocations that shape what might take us to abolition. Time is garbled here, and maybe that’s the point.

“There’s nothing new under the sun, but there are new suns.”

—Octavia Butler

Lauren Williams (she/her) is a Detroit-based designer, organizer, researcher, and educator. She works with visual and interactive media to understand, critique, and reimagine the ways social and economic systems distribute and exercise power. Her practice and research investigate Blackness, identity, bodiliness, and social fictions and examine how racism is felt, embodied, and embedded into institutions. Lauren’s work often engages people through collaborations and facilitated experiences in service of imagining and manifesting a more liberated present and future. Lauren has taught design at the College for Creative Studies, ArtCenter College of Design, and elsewhere. In the past, she has managed programs and policy aimed at cultivating economic justice at Prosperity Now in DC. Going forward, she's finding ways to align her capacities with revolutionary movements that build toward a different economy entirely and usher in new dimensions of power and freedom altogether.

This text was produced as part of the Against the Grain workshop.