A lecture over Zoom is a common practice since COVID-19 disturbed and disrupted our world, impacting life as we know it and relegating education and work to square boxes on a screen. Brazilian curator, Artistic Co-director of Museu de Arte Moderna do Rio de Janeiro, writer, researcher, and educator, Keyna Eleison, begins by acknowledging that making and unmaking is work that never stops. In her experience as a Black woman, it is crucial to understand “what we can make, and what we can and cannot unmake.” For Keyna, one recurring theory has been around more of “what we don’t see”—the theme in which she actively engages the audience to participate by turning off her camera. Under a black Zoom square, her voice continues: “You can hear me, but you cannot see me. I can tell what I’m wearing, I can tell you everything that I am thinking now, but you cannot see me. I can tell you that I smell good, and all around me, I have the smell of cooked beans, I hear the chatter of children, and that here in Rio de Janeiro, it is very, very warm. But I can tell you that I’m missing a lot—I’m missing people.” By switching the camera on again, the example concludes with the point: that time affords power, and power brings the understanding that sometimes we are not visible because we prefer not to be, not only because this structure makes us invisible. In this transcribed and edited lecture, Keyna shares her experience as a Black female curator, what that signifies, and what can be learned from other systems of knowledge and cosmologies.

I do not look like a curator. When someone sees me, they don’t see a curator. A curator, when I was growing up, would not look like me. It was a guy—usually a white guy, speaking English, or some other Eurocentric language. Then I realized that Portuguese, the language that I learned, which is now my language, is a Eurocentric language too. This is another thing that I could not see; I have more languages in me. Languages that I cannot speak or verbalize, but I can feel, I can wear, I can smell, I can dream, and I can be. Why am I saying this?

Because I am a curator. And when I could start to think that I am a curator, I could say it in other languages. I could say this phrase with a huge and beautiful smile: “I am a curator.” And I know that with movements in me, I can start collective dreams. People that look like me will see a curator and understand that they, too, can become one.

When people start to see me, I can spread the idea that these don’t need to be extraordinary movements. I dream with the ordinary. I dream with the normal. I dream with the regular. I’d really like to look at the mirror and understand that I am not the most intelligent or the most anything. Being extraordinary makes us think that we’re alone, and this I shouldn’t think—I’m not alone. I’m with a lot of women, men, children, and friends that make me more understandable and more real.

What I can see is not everything, and what we cannot see is sometimes more violent than caring. If this structure leads us to loneliness in victories… I don’t want it! It is enough to be aware that being in a feminized and a racialized body, you are often alone. We are a whole generation that understands that only one person can win, or you’re obscured in a collective mistake. As a woman, particularly as a Black woman, I understood myself from since I was very, very young as being wrong. Not that I was a mistake, but I was wrong. “The truth” came with my teachers, who were always white people, and most of the time men. Not only my teachers, but also the books that I read or were deemed important were written by white men. How can I say something around the body and not speak about French philosophy, or cite those scholars? Why can’t I speak about the body, art, the Orishas, the wind or a lot of things that the structuralized intelligence doesn’t see as intelligence or epistemological ways of doing, knowing, or learning? Learning is also about the invisible. It’s around the weather; it’s around a pandemic wave.

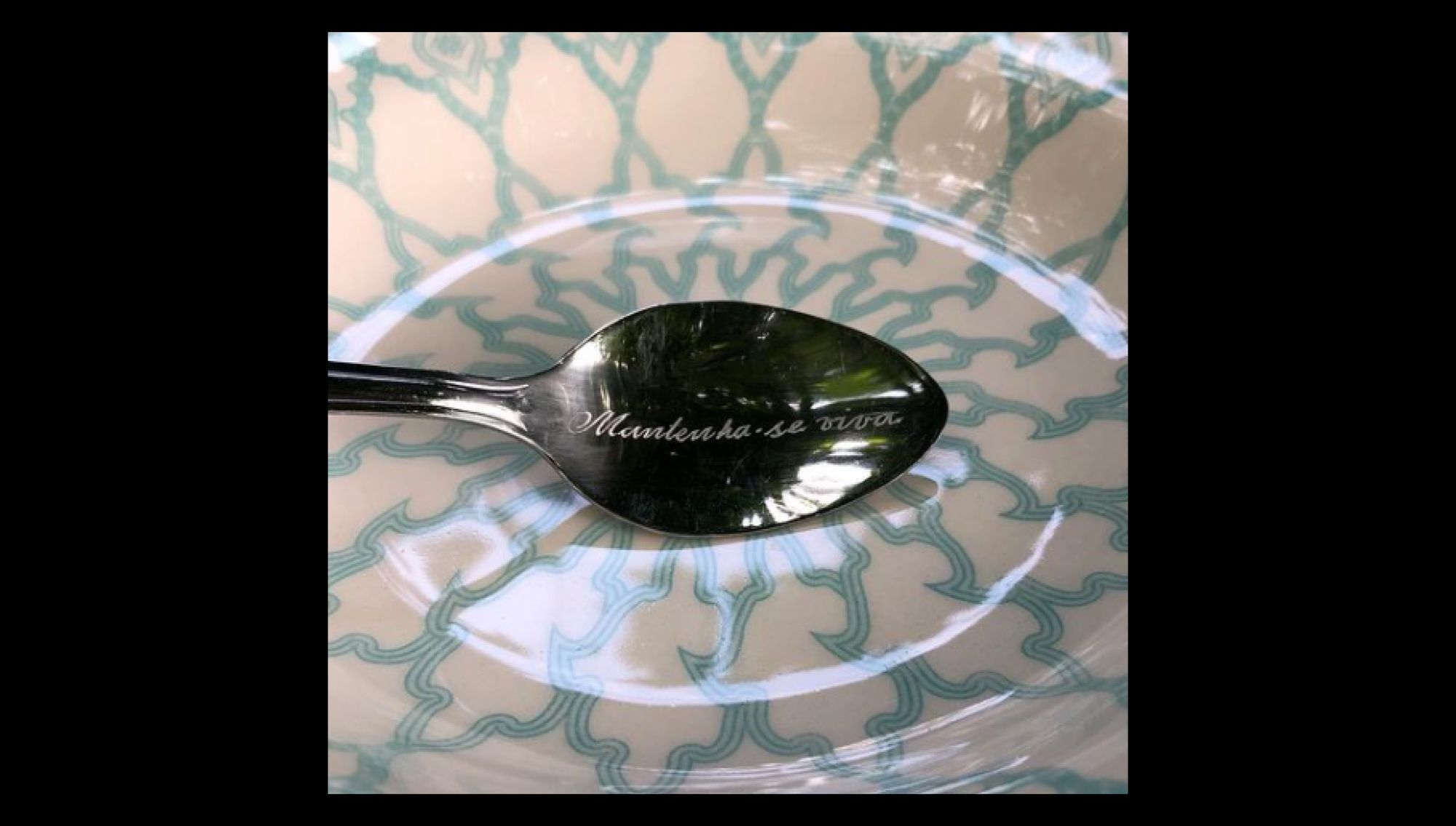

“Sometimes you need to close your eyes and feel with other parts of your body.”

If art and struggle are linked, as instrumentalization and the tool for instrumentalizing thoughts, how do we deal with these segmentations? How do you understand yourself on one side of humanity, and realize your responsibility even if perceiving it? How do we understand what is true? How do we understand what is right? We learn it. We learn and maybe this is a passive way to understand things, but you can activate this passivity to understand things that maybe you don’t see. Not because you need glasses, but sometimes you need to close your eyes and feel with other parts of your body. As a curator, that is my responsibility: to understand that not everything that I see is a complete truth or is a complete view of all understandable things. Maybe ending the phrase with my smile when I say “I’m a curator” is stronger than when I just say I’m a curator. Maybe only my smile says that. Maybe only my way of doing things says that.

There are multiple ways of doing things—we have more ways to understand, more ways to meet, to know, and to change. In the multiple forms of knowledge, you need to understand, to realize how to connect, and how to respond to situations. There is a Nigerian saying that has really impacted me, of the effects of boiling water on an egg, a potato, and a coffee bean. The same hot water that makes the potato softer makes the egg harder, and the coffee beans affect the water by making it a delicious drink. Sometimes you cannot change how hot the water is, but maybe you can understand whether you are an egg or a potato. I like both. Sometimes I’m the egg; sometimes I’m the potato. It’s harder, but sometimes, you can be both. The key is understanding when to be harder or softer, because we can become different persons at different times in different circumstances.

Art and curating, choosing and being chosen, are movements of being connected. But even more important, is to understand how to disconnect. Sometimes you need to leave something that you like, or love, or need to make space for other things around it. Disconnection comes not only in the digital way of turning off the telephone or the computer, but in reality as well. How can I disconnect, detach the link with some things? How can I remove some people from my life, some subjects, arguments, and movements which no longer are beneficial? How can I pay attention and become more specifically the curator that I really want to be? How can we unmake the idea of individuality against collectivity?

These are not dual forces, but to understand that, we need to change our language. We need to change how we think. We need to start to unmake the idea that our body is completely split. We acknowledge that we have parts, yes, but we are one and more. How can individual performance have a collectivity? How can my work here make things different from the world? How can I care, look and annotate to make the structure change?

I could talk about being healthy because, for me, it’s very important to understand what it takes to be alive. To be healthy is not an individual but a collective experience.

“Maybe [we need to] understand how we can put the darkness not as a comparison to the lightness, but something that combined can bring us more definition.”

How can we look around, and understand what we don’t see, to start something? What is completely clear, what is completely inside of the light is not so interesting. I like to think about movies: when we are inside the theatre with the lights off, we sit, but we are only able to watch what we came there to see. We need more definition. We need to understand the shadows. We need to understand its colors. We need to understand the sound better when the lights are off. Maybe understand how we can put the darkness not as a comparison to the lightness, but something that combined can bring us more definition. We can make ourselves more understandable.

The sum of my being—everything that I am thinking, saying and doing—is about art, because I am a curator. I like that I’m talking about art, because this is the way that I can work. How can I choose the connection that I have? How can I choose the artists to whom I really want to be connected? How can I embrace a kind of production or a kind of research that is in line with my praxis and beliefs? How can I write or not write? How can I stop my research? How can I pay attention to something, and leave another thing be?

I have more questions than answers, but I’m not here to be an answer. This is something that people sometimes don’t see: how projecting female or feminized bodies and racialized bodies as answers for huge questions around anti-racism, anti-capitalism, anti-ableism and anti-classism is something very, very violent. My body, and bodies like me, cannot be the answers for questions that we did not formulate. I can choose to show more people that this can be a problem. When you see a Black woman, or when you see a woman, or when you see a feminized body as “answers” that may be the cure of these problems, when it was not that body that made these problems, this is violent.

“The comparison of these struggles is something that our systems are doing with us, and sometimes it makes us separate our way of thinking.”

My understanding is very open to being and doing a collective understanding, but I’m not the answer. My body being inside a place doesn’t make the place better. Having only one body does not make a place better or more intelligent. But sometimes quantity is quality. We need more women; we need more Black women inside these places, inside the exhibitions, inside institutions, inside of and part of the knowledge creation processes. We don’t need to understand further that we need to fight. However, I don’t want to fight forever. I really, really—just—want to be normal! I don’t want to be someone who needs to struggle so much to understand, and struggle to smile. We need to understand that sometimes my smile is a product of a lot of struggle—a struggle which is not only mine. Sometimes my struggle is bigger, but that doesn’t make the struggles of other persons unimportant or of less importance. The comparison of these struggles is something that our systems are doing with us, and sometimes it makes us separate our way of thinking. This is something that we don’t see.

Keyna Eleison (she/her) has an MA in Art History and a BA of Philosophy. She's is member of the African Heritage Commission for awarding the Valongo Wharf region as a World Heritage Site (UNESCO), and was a curator of the 10th. International Biennial of Art SIART, in Bolivia. Currently, she's a chronicler of Contemporary & Latin America magazine, and Professor of the at the School of Visual Arts at Parque Lage, Rio de Janeiro. She's also Artistic Director of the Museum of Modern Art in Rio de Janeiro mam.rio in partnership with Pablo Lafuente.

This text is a transcript of a lecture that was part of Making and Unmaking Exhibitions: Sustainability in Times of Planetary Crisis, a series of lectures reflecting on a more sustainable cultural sector. The series was a coproduction by the Centre culturel suisse. Paris and Futuress.

The text has been edited for brevity.

Visit our Lectures section to watch the recording.

The title of this vertical, Vulnerable Observers, is an homage to anthropologist and author Ruth Behar and her book “The Vulnerable Observer: Anthropology That Breaks Your Heart.”