Victoria Nascimento Veiga had always dreamed of working in fashion—a lifelong aspiration she believed was out of her reach. She never cared about fashion weeks or cycles. Fashion, for her, has always been a mode of communication, an outlet for self-expression, a collective doing, a togetherness. At seventeen, the designer from Vila Nancy, a low-income neighborhood or favela in the Eastern São Paulo District of Guaianases in Brazil, became an apprentice at Faculdade Santa Marcelina, a private university with tuition fees nearly three times the Brazilian minimum wage. A year later, she was formally employed, and with her new contract came an exciting prospect: a full scholarship.

“I had to develop a collection, and I found myself imitating European fashion.”—Victoria Nascimento Veiga

“In the beginning, I felt out of place, left out, excluded,” Victoria says, reflecting on her early experiences as a student in 2019. While Santa Marcelina offers discounted tuition for students from public schools, most of her peers came from middle-class or upper-class backgrounds. The following year, the COVID-19 pandemic hit Brazil hard, with the country swiftly rising to rank second in the world for the highest number of Coronavirus deaths—an impact that was particularly felt among the most vulnerable populations, including those from the favelas. Against this backdrop, the less privileged also faced the brunt of the struggle to adjust to the changes in all areas of their lifestyles, including one aspect that was most urgent to many at the time: education. For Victoria, all her classes became remote, which was particularly challenging for such a hands-on course, as she didn’t have her own computer or sewing equipment at home. It was during this time that she was introduced to styling, a course spanning two semesters. “I had to develop a collection, and I found myself imitating European fashion,” she explains, describing her first designs: a nondescript series exploring the Zodiac signs. Later that year, her boyfriend, an emergent rapper from Guarulhos, passed away before releasing his first record. “It was a devastating blow. As I listened to his songs again, I realized that I, too, am a person from the favela. Being favelada isn’t about the clothes you wear or the music you listen to; it’s about your lived experience.”

“Making clothes is so expensive. How can I make my work valuable for the people in the favelas, the people I care about?”—Victoria Nascimento Veiga

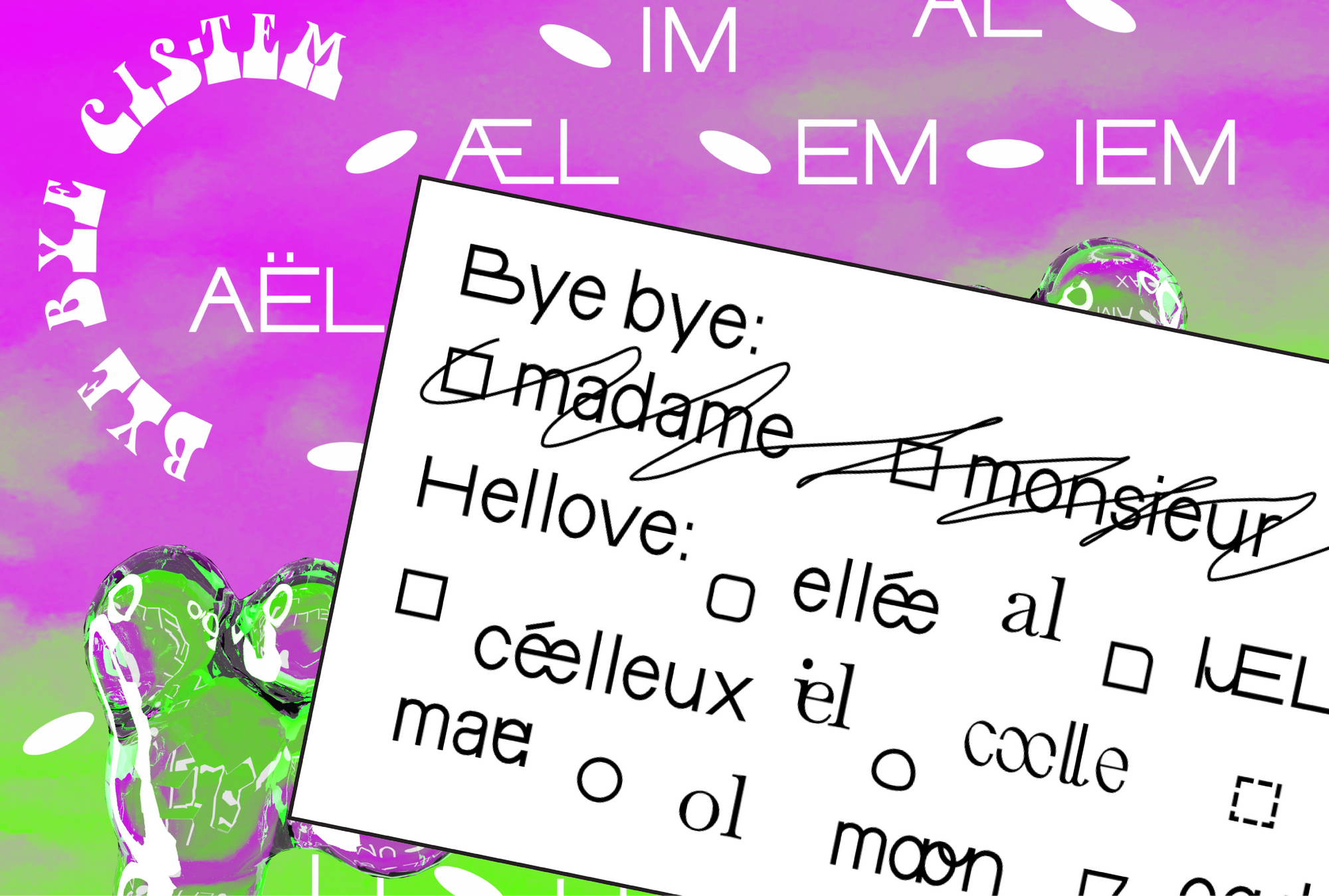

In the second semester of 2020, Victoria started her project. At first, she faced resistance from her teachers, who didn’t want her to change her topic halfway through the school year. Determined, she started looking for ways to represent the favela through references, textures, and materials. “I wanted to politicize myself, to understand myself as a favelada, as a Brazilian citizen,” she states. Victoria’s research led her to confront the fashion industry’s systemic exploitation, exposing how streetwear brands extract symbols from the favelas to create garments that are ultimately inaccessible to the very people living there. “Fashion school shaped me and made me aware of the limited space I had to express my voice, knowing I wouldn’t always be heard and listened to,” she explains. Throughout her studies, Victoria experienced a lack of representation. It wasn’t until her fourth year that she had a Black teacher, and even then, the teacher taught the students about entrepreneurship rather than fashion specifically. For Victoria, representation is at the heart of what she believes in, and it has become the source of her excitement, fuelling her passion for purposeful design. She notes: “Making clothes is so expensive. How can I make my work valuable for the people in the favelas, the people I care about?”

Victoria is a finalist for the 2023 Tomie Ohtake design prize, and as a jury member, I have been closely following her journey over the past few months. Since our first conversation, I have been impressed by her no-bullshit, no-nonsense approach, coupled with a contagious sense of joy and excitement. Victoria describes having a small epiphany during a third-year class on accessory design when she developed a modular collection of transformable bags. “That’s when my interest in sustainability was sparked,” she explains, with a sharpness that matches her impeccably applied eyeliner.

“Fashion has historically been both a symbol and a tool of segregation and exclusion. For that to begin to change, the favela needs to dictate its own fashion.”—Victoria Nascimento Veiga

Victoria is aware of the complex entanglements between climate justice and social justice. According to the 2018 Fashion Transparency Index, Brazil has the world’s fourth-largest fashion industry, employing almost 1.5 million people, with 75% of them being women, many of whom live in the country’s favelas. Meanwhile, a recent study shows that 29.6% of the Brazilian population lives in extreme poverty, the highest rate recorded since the historical series began in 2012, mainly due to the impact of COVID-19. At the same time, the 2022 Fashion Transparency Index exposed how most surveyed Brazilian fashion brands do not disclose the waste they generate, and while deforestation rates in the country continue to escalate, no brand has yet committed to zero-deforestation plans. “All of these issues are interconnected,” Victoria asserts, clarifying that, for her, “sustainability without class struggles is just gardening.” All of these issues are interconnected," Victoria asserts, emphasizing that she is echoing the words of Brazilian environmentalist Chico Mendes, who stated, "Sustainability without class struggles is just gardening

“Fashion has historically been both a symbol and a tool of segregation and exclusion. For that to begin to change, the favela needs to dictate its own fashion,” she says. At the same time, people from the favelas practice sustainability on a daily basis, receiving and repurposing used clothes. “It’s nothing new,” she remarks. Yet, most so-called “sustainable” fashion products—from recyclables, upcyclables, or made with fancy materials like vegan leather, are exorbitant and accessible only to a privileged few. “There’s also a lot of talk equating sustainability with expensive, high-quality clothing that doesn’t wear or tear and can be passed down through generations. But a favelada endures misery and deprivation for so long, that when given an opportunity, they will choose to buy a new outfit. For the person in the favelas, used clothes are not ‘cool vintage.’ On the contrary, they negatively impact one’s self-esteem—they are extensions of feelings of abandonment, precarity, and social displacement. That’s why, for my final project, I wanted to design a product that was and felt new despite being made from recycled material.”

In the favelas, sneakers have a special status and affective value—they symbolize achievement and validation, as echoed in Brazilian rap, hip-hop, and funk songs. Understanding this cultural significance, Victoria decided to develop a collection of shoes. She conducted numerous tests to find her material: high-density polyethylene bottle caps, which are carefully washed, sliced, sorted into predefined color combinations, then melted together to form a solid, marbled block, which is later manually sculpted into a sole. To enhance comfort and reduce the footwear’s weight, Victoria punched circular holes and repurposed the removed material into colorful earrings. Used plastic bags were ironed to create a soft upper cover, and the shoes were finished with bright laces. The end result is a poppy kaleidoscopic collection of six unisex platform shoes. Although visually striking, for me, the magic lies not in the final result per se, but in the process that led to its creation.

Due to the drastic decrease in volume when melted, Victoria needed a seemingly infinite number of bottle caps. She started a social media campaign and placed a collection box at the entrance of her school, but neither of these strategies seemed to work—she only managed to gather 200 caps, or only one-fifth of what she needed for a single shoe. “It was the word of mouth that made my project happen,” she explains, attributing the success of collecting the 6207 bottle caps used in the project to her mother, Edna do Nascimento, who works as a housekeeper. Victoria’s mom mobilized a network of over 40 families, mainly from Vila Nancy in Guaianeses, who contributed the caps from their domestic consumption.

“In most government-led recycling systems, people are unaware of what happens to the material that gets recycled. I wanted to involve them in the process and make them active participants.”—Victoria Nascimento Veiga

“The soul of my work lies in the collection, and the collective,” Victoria explains. “In most government-led recycling systems, people are unaware of what happens to the material that gets recycled. I wanted to involve them in the process and make them active participants.” To achieve this, Victoria shared her entire design process through social media, opening polls about design choices and discussing her successes and struggles. “For a long time, my followers couldn’t quite visualize the final product, which sparked immense curiosity. They asked: how on earth will you transform these plastic caps into shoes?” This ongoing engagement spanned eight months, during which Victoria developed a strong connection with her public, learning from their insights and comments, and evolving alongside them.

“I made every effort to involve the community in this project.” she explains. Her final step was inviting a street artist to tag the finished shoes—an idea her teachers strongly opposed. The artist, Thiago Sassen, hand-drew the final pixos, the calligraffiti style of straight lines and sharp edges that is especially prevalent in São Paulo. “Pixo is a form of communication that is often appropriated by streetwear and perceived as cool, but when people come across a wall with pixos, the reaction is different—they find it’s ugly and poor. I wanted to bring the pixo to my work not only as a representation of the favelas, but as real art,” Victoria points out.

Ultimately, her collection is not scalable. It takes nearly two weeks to produce a single pair of shoes, not to mention the time required to collect the materials. But scalability was never her true intention. In fact, Victoria’s goal wasn’t even to develop a “fashion product.” Instead, she aimed to engage her community—the people she deeply cares about—in a collective learning experience. “For me, this project is about education, about raising awareness, about re-centering the fashion gaze,” she states. This intention is particularly evident in the final videoclip she produced to showcase her collection, which stars her own friends and was shot in the streets of Vila Nancy by a local filmmaker. “Above all else, I’m from the favela, and I will create fashion as such,” she concludes. And with that, fashion might just get a small chance to reinvent itself.

An earlier version of this article appeared in the catalog of the 2023 Tomie Ohtake Prize.

October 31, 2023

In our article originally published with the sentence: “All of these issues are interconnected,” Victoria asserts, clarifying that, for her, “sustainability without class struggles is just gardening," we would like to make a necessary amendment to attribute the quote and its origin properly.

Upon further research and clarification, we want to emphasize that "All of these issues are interconnected" is not solely attributed to Victoria Nascimento Veiga but is a quote by Brazilian environmentalist Chico Mendes. We apologize for any confusion caused by the previous publication.

Victoria Nascimento Veiga (she/her) is a Brazilian fashion and footwear designer. Hailing from the Guaianazes neighborhood in the eastern outskirts of São Paulo, Brazil, her work addresses segregation and circular economy issues. Her practice aims to make fashion knowledge and sustainable fashion more accessible. In 2023, Victoria participated in the 5th Tomie Ohtake Design Award with her project KIT011, centering design under a peripheral vision. Recently, she graduated in fashion from Faculdade Santa Marcelina in São Paulo, Brazil.

KIT011 is a shoe and accessories collection that proposes to establish a dialogue between sustainable fashion design and peripheral communities. Aiming to represent and create identification, KIT011 consciously brings in peripheral culture, its perspectives, and symbologies through collaborative processes. Victoria’s collection uses recycled everyday material such as polyethylene bottle caps and plastic bags collected through a campaign in her neighborhood of Guaianazes in São Paulo, Brazil. Through this approach that centers on collectivity as part of the production process, the project highlights the value of creating a network of sharing and engagement. Rather than looking for sustainable “solutions,” itt aims to bring discussions around sustainability into the daily life of the Guaianazes community.

Nina Paim (she/her) is a Brazilian designer, curator, and editor based in Porto. Her work spans exhibitions, workshops, and events, including Escola Aberta (Rio de Janeiro, 2012), Beyond Change (Basel, 2018), Department of Non-Binaries (Sharjah, 2018), Feminist Findings (Berlin, 2020), and, most recently, Etceteras: Feminist Festival of Publishing and Design (Porto, 2023). She has co-edited Taking a Line for a Walk (Spector Books, 2016), Design Struggles (Valiz, 2021), and Alter-Care (Esad-Idea, 2021). A three-time Swiss Design Award recipient, Nina has lectured internationally and her writing has been published by Occasional Papers (UK), Les Presses du Réel (FR), and the Korea Society of Typography (KR). In 2020, she co-founded the feminist platform Futuress.org, which she co-directed until 2023, when she launched Bikini Books, an independent publisher for design. In 2024, Nina was awarded an honorary doctorate from the London College of Communication at the University of the Arts London.

Title image: KIT011 shoe collection by Victoria Nascimento Veiga (Photograph by Victoria Nascimento Veiga)