Trigger warning: Before you start reading, please note that there are graphic descriptions of violence in this text.

Shocking statistics are published year after year, exposing the numbers of femicides and other incidents of gender and domestic violence in Latin America. “It’s always the same graphs, included in the same design concepts, and eventually it ceased to have an impact,” says Brayan Pinto, one of the creators of Nos Estan Matando (“They are killing us”), an experimental book raising awareness of the femicide epidemic in Peru through inventive graphic media. “As visual communicators, we have the responsibility to present new concepts, which transmit ideas more efficiently and connect emotionally with the audience.” Brayan and his partner Adriana Quesada felt compelled to use design as a vehicle to disrupt the apathy towards gender-based violence that is present in their country.

“Domestic violence always increases in times of crisis.”

Like almost everywhere in the planet, COVID-19 has increased violence against women in Peru. However, this was a longstanding problem even before the pandemic, with an average of five women or girls reported missing every day. With the pandemic, these numbers have not lowered in the slightest, which means that in a country where lockdown restrictions were enforced by armed officers, these women and girls are likely “disappearing” from their own homes. According to a UN study, home is the most dangerous place to be for women globally, with 58% of female homicide cases being committed by someone the victim is close to. A rise in cases of intimate violence or even femicide could have been predicted, Maclen Stanley writes in Psychology Today. As noted prior, domestic violence always increases in times of crisis, for example in 1989 after the Exxon Valdez oil spill in Alaska, and after Hurricane Harvey in 2017.

It is impossible to say with certainty how and why these women and girls disappear, but very little effort has been made to gain clarity on this problem. There is no consistent protocol on how to catalogue missing women, whether they turn up dead or alive, or under what conditions they went missing. Peru’s women’s rights representative at the Ombudsman’s Office, Eliana Revollar Añaños, suspects many of the missing women and girls in Peru are either femicide victims or on the run from abusive men, she told the BBC. Remarks by the Peruvian government have fueled the idea that femicide is not taken seriously, with former president of the congressional committee on women’s rights stating that women are killed because “sometimes, without thinking, women give men the opportunity.”

These horrid facts and lack of effort to create reliable statistics have ignited public outrage. In 2016, the feminist grassroots organization NiUnaMenos, which was founded in Argentina, formed a Peruvian chapter and staged the largest public protest in the country’s history. The demonstration was a display of indignation following the release from jail of a convicted man captured on video attacking his girlfriend in a hotel in the city of Ayacucho and dragging her by the hair. The organization is revolutionary not only in terms of drawing large numbers to protest; the reach of their testimonies was unheard of, and NiUnaMenos has made alliances with state institutions to ensure their demands are heard.

“It [femicide] is not approached with the seriousness and responsibility necessary on the part of the authorities to make significant changes.”–Brayan Pinto, one of the creators of the book Nos Estan Matando

In spite of these mobilizations, crimes against women still have few consequences. In Peru, femicide was penalized in 2013, but public and state response is still insufficient. Between 2009 and 2015, only 84 convictions were made although 795 cases of femicide were reported. “It is not approached with the seriousness and responsibility necessary on the part of the authorities to make significant changes,” says Pinto.

He explains that one chapter of the booklet compiles comments on a press release on Facebook about a 2018 incident of one of the most shocking femicides in Peru’s history: 22-year-old student Eyvi Agreda was set on fire by a stalker on a bus in Lima. Crude comments about her consequential death were common; as Pinto says: “The result was quite depressing, since the comments reflected a lot of the cruelty, indifference and machismo in Peruvian society.” A notable example of this was Peru’s president’s response to the homicide: he stated that “sometimes, that’s how life is.”

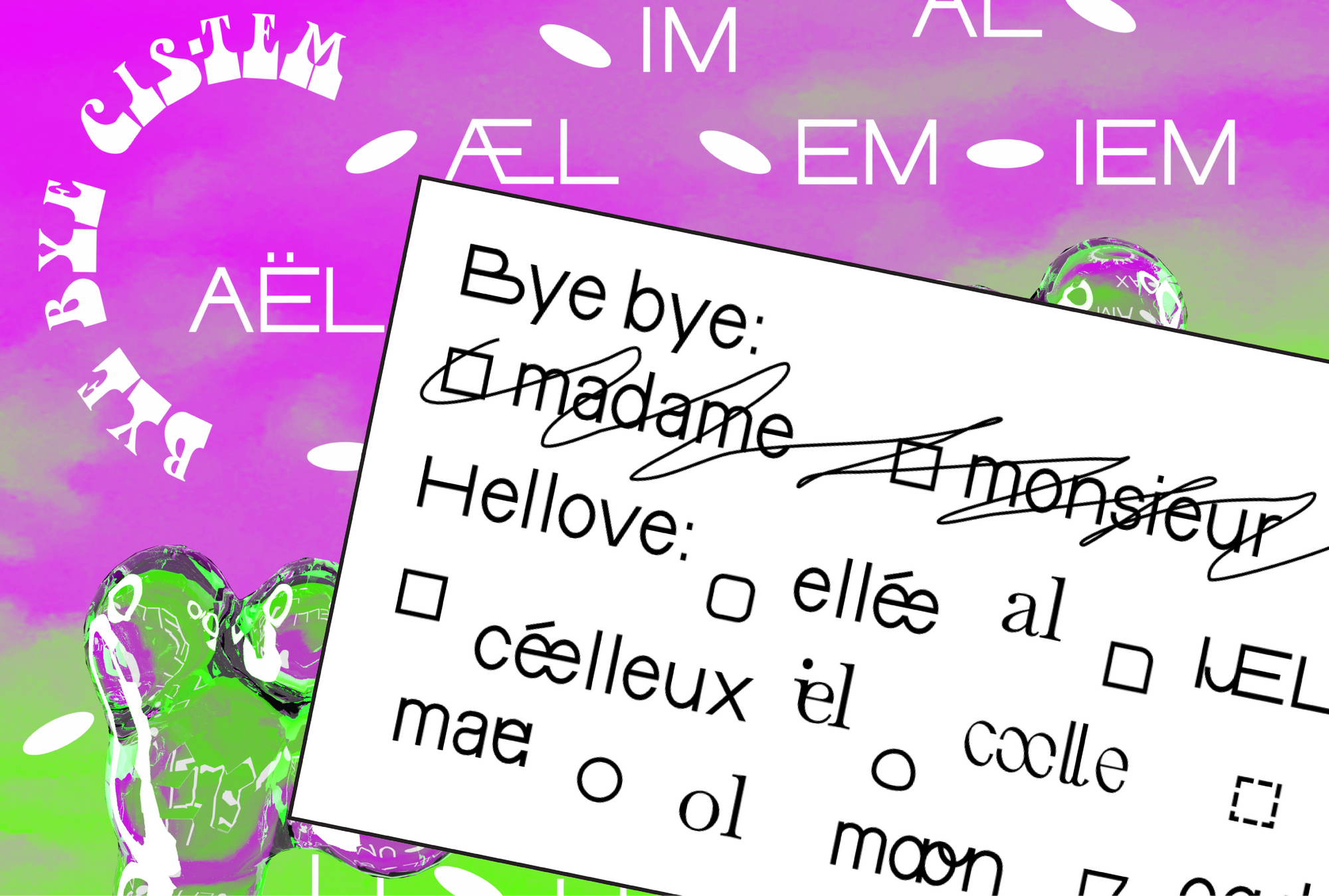

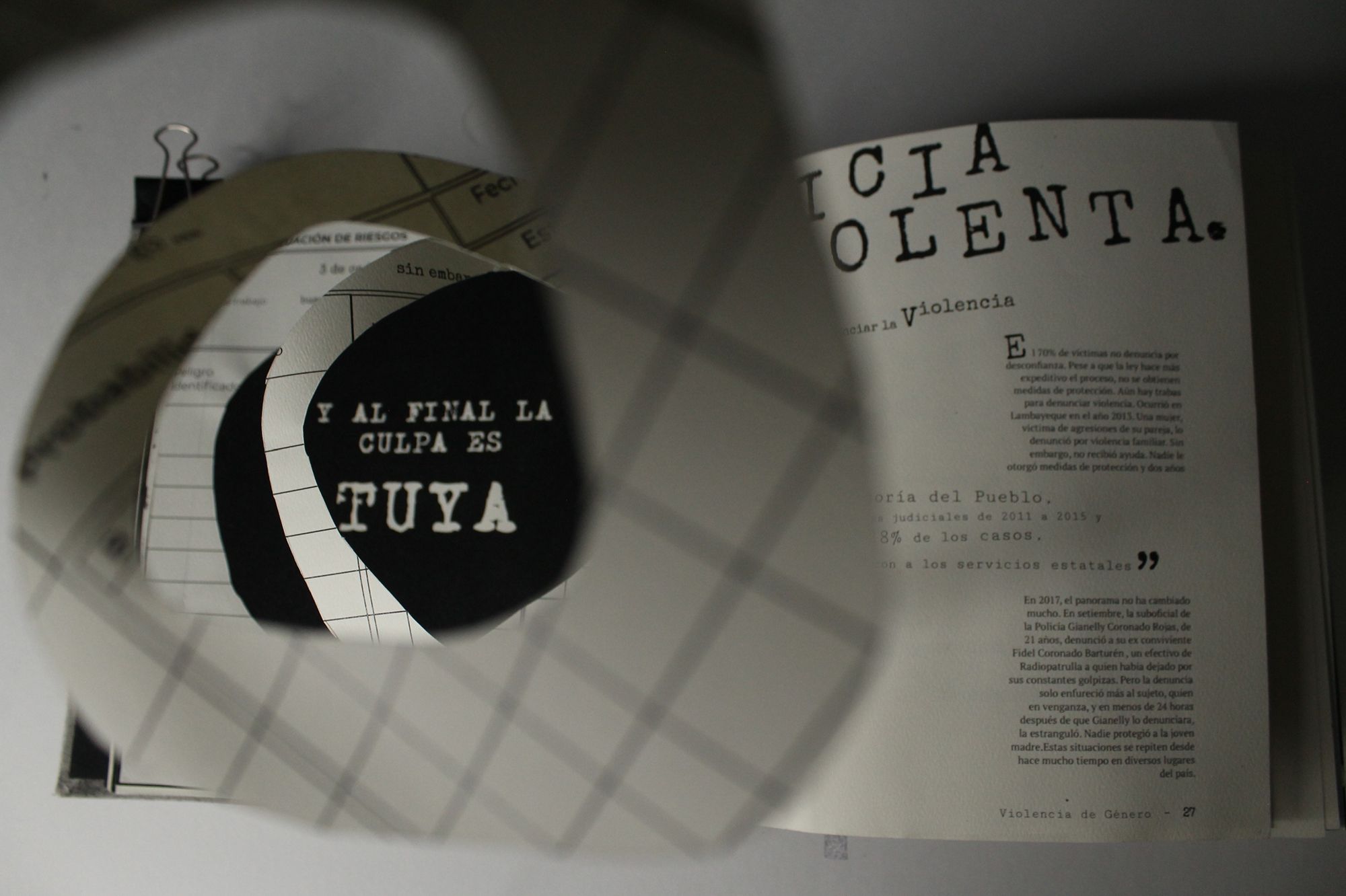

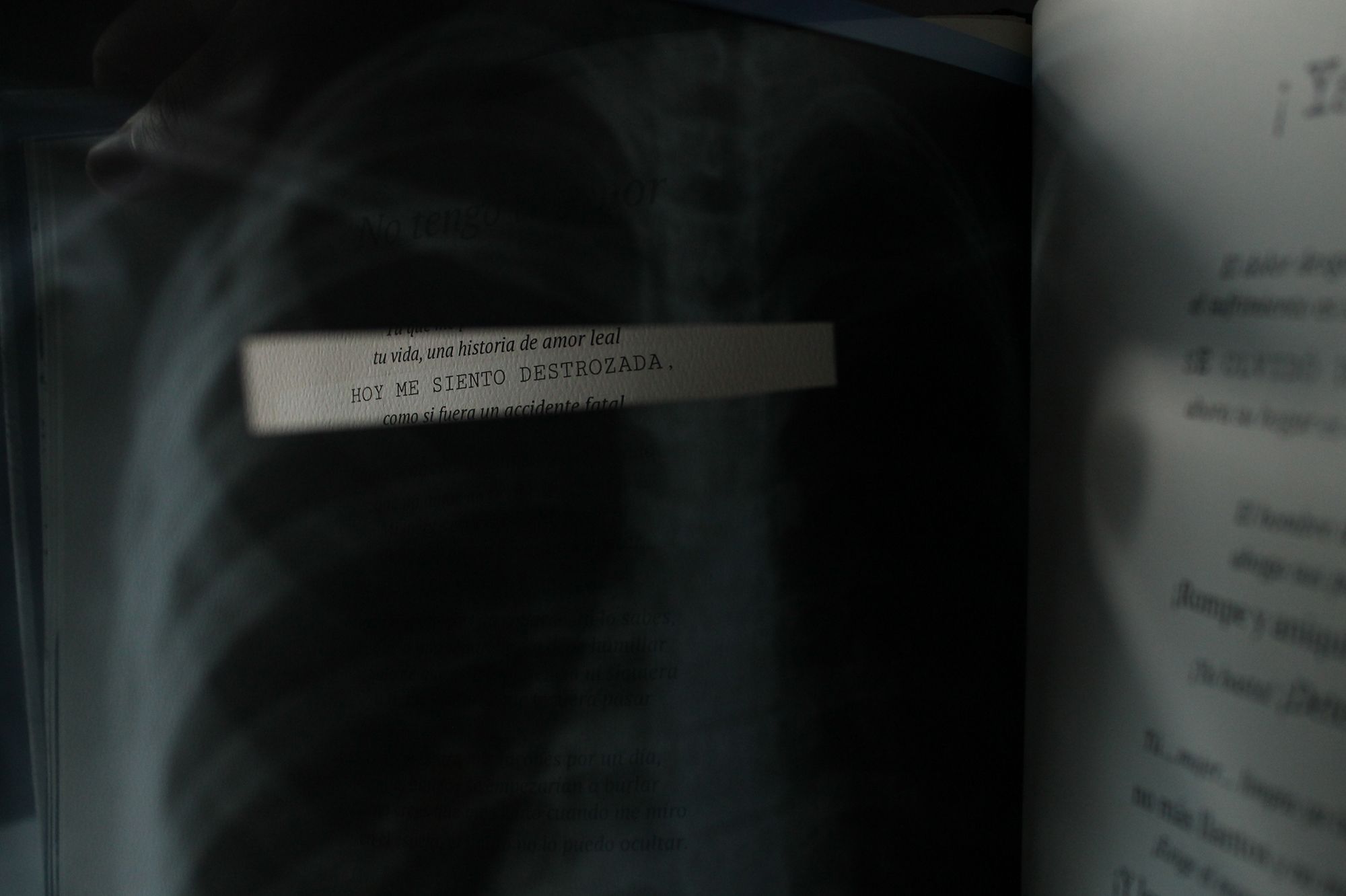

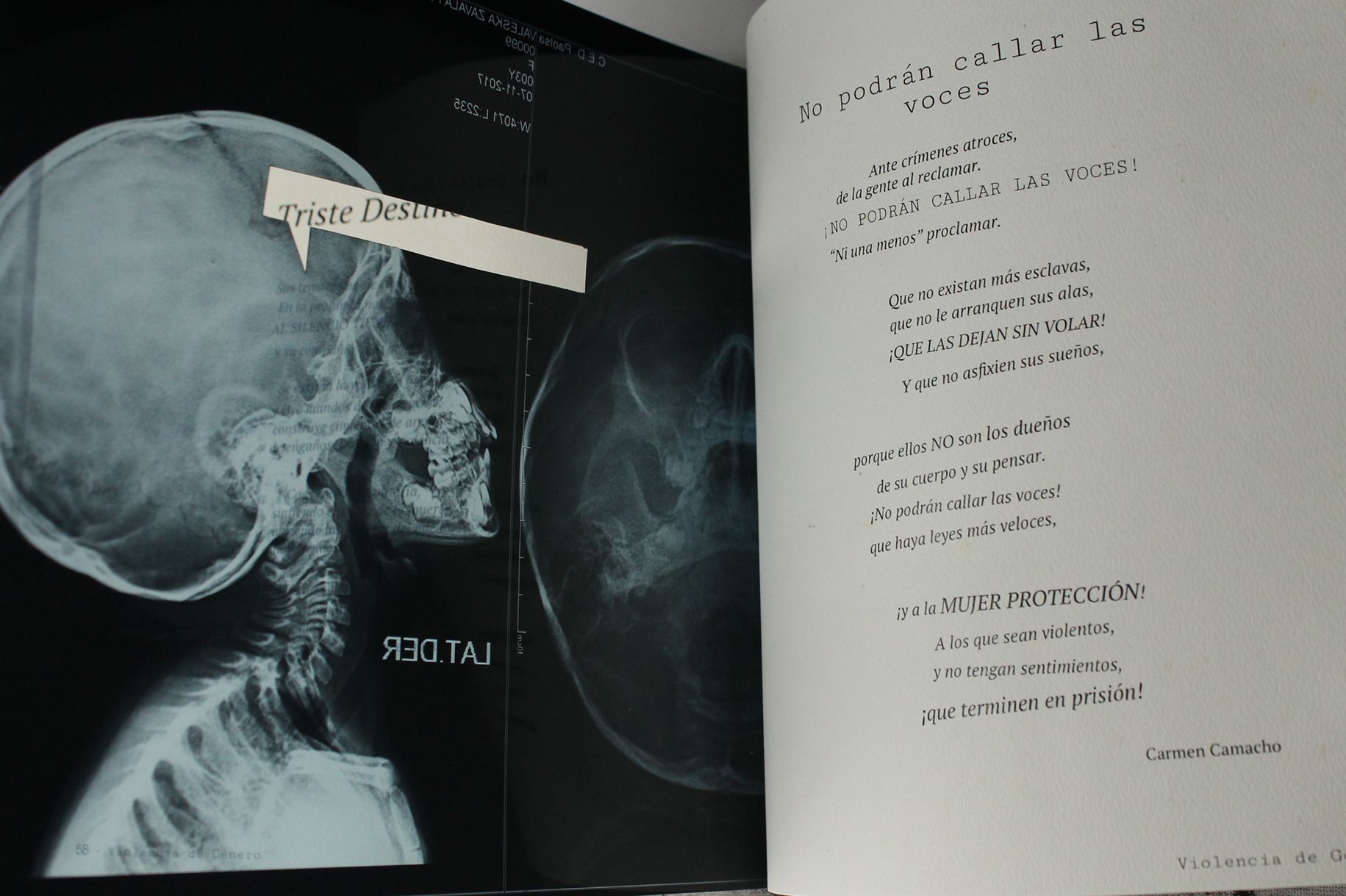

To break with the tradition of apathy and victim-blaming in Peruvian discourse around femicide, Brayan Pinto and Adriana Quesada conceived what they called a libro-denúncia—a “complaint” or “denouncement” book. Their design combines synergistic elements with journalistic insights, visual storytelling and poetry to raise public awareness and underline the fact that this national problem calls for urgent action. These tactile elements manifest through “tabs, flaps, letters, breakable images, and hidden pages that the reader has to interpret to understand the message.” This way, the viewer of the booklet has no choice but to actively engage with the horrid reality of femicide. “Visually, the book represents a complaint. Its look is inspired by the forms people have to fill out in cases of violence, which usually result in little investigation or action. The rugged aesthetic of the booklet is meant to emphasize the concept of infection or dirt to the reader, to convey the concepts in a more emotional way.”

Violence against women is widespread across Latin America, in part because of the region’s violent colonial history, layered by further histories of political and military sexual violence. According to Pinto, the prevalence of gender-based violence as well as the lack of response to femicide cases, also has to do with prevailing gender norms and machismo. Machismo is a model of masculinity that emphasizes violence and domination, which came to Latin American countries by the Spanish conquest. It was a colonial response intended to eradicate indigenous gender expressions. “Gender stereotypes perpetrated in Latin America continue to be celebrated. Since we still do not have a correct education with a gender approach, this means that women who stop complying with these stereotypes are victims of gender violence, and in the most serious cases this can escalate to a femicide,” says Pinto. Through collages and visual metaphors, Pinto and Quesada link the femicide issue with Peruvian cultural aspects, such as religion and machismo.

“The prevalence of gender-based violence as well as the lack of response to femicide cases, also has to do with prevailing gender norms and machismo”

“I definitely think that a design booklet is not the end-all solution to the problem, since to solve it requires an effort from society in general at different levels, such as educational, judicial and social,” Pinto states. Still, he and Quesada hope to set a precedent and amplify the ever-growing feminist movement in Peru in stating: the conversation about femicide needs to change. Gender-based violence should be treated as the epidemic it really is, which demands to be treated with urgency and priority, instead of being seen as the status quo. “Everyone’s support, in one way or another, can promote social change,” concludes Pinto.

Tessel ten Zweege (she/her) is an Amsterdam-based feminist author, currently writing a book on intimate partner violence. She is pursuing the master's degrees Gender Studies at Utrecht University and Crossover Creativity at Utrecht School for the Arts.