The COVID-19 pandemic has challenged society in drastic and unprecedented ways. Not only due to the direct health consequences of the virus but also because the precautions taken against its spread transformed many peoples’ lives and will continue to do so for quite some time. Working environments have radically changed, leisure times still have to be re-organized, and new ways have to be found to stay in touch with loved ones. Besides the huge humanitarian and economic toll, the pandemic has created a need to design new strategies to deal with these changes to the social fabric.

In Germany, where I live, according to the Institute for Communication and Society (IKG), changes in social life in 2020—such as keeping distance, restricting contacts, and closing public spaces—have contributed to an increased feeling of isolation and loneliness, in particular for people who are not in a partnership or do not have a family. An evaluation on mental health during the pandemic, published by the German Socio-Economic Panel in July 2020, further showed that in Germany loneliness almost doubled since 2017. Contrary to expectations, these statistics also indicate that it is not the elderly who suffer the most from isolation, but rather young people around thirty years of age—a tendency that was already evident in the 2017 surveys. But what actually is “loneliness”? And what can be done against it?

“Loneliness is [...] not primarily about a change in relationships and social contacts, but rather about a persons’ own identity, needs, and sense of belonging.”

When speaking about loneliness, the term is often mistakenly equated or interchangeably used with “isolation.” However, even though isolation may be a big cause for people to feel lonely—especially nowadays during the pandemic—the two aspects are not inevitably linked. A paper from 2018 by the UK Government, titled “A connected society: A strategy for tackling loneliness,” describes loneliness as a very subjective feeling that is not always related to being alone. That is to say, a person can still feel lonely even if maintaining many social contacts and on the other hand, a person who prefers to be alone is not necessarily lonely. Loneliness is a feeling that there’s something lacking in ones’ relationships and social networks; a desire for more social contacts, deeper relationships, or other forms of community. It is an imbalance between the contacts wished for and the actual relationships one has.

According to the same paper, various events may trigger such an imbalance, such as changes of personal circumstances—moving to another city, unemployment, or the loss of a loved one—as well as changes within a family—becoming a mother, becoming a care-giver, or when a child leaves home. Besides these personal factors, the survey also names social change as a key role. In working environments, for example, even for people sharing an office with others, workload and pressure to perform can discourage social interaction. Another set of factors that the previously mentioned Institute for Communication and Society (IKG) names are individualization and technological developments, which while offering greater flexibility in shaping both private and professional lives, often lead to less direct interaction with others.

Even though these personal and societal circumstances can be a cause, loneliness is also not primarily about a change in relationships and social contacts, but rather about a persons’ own identity, needs, and sense of belonging. This means that loneliness can also be deeply rooted in one’s biography and connected to trust issues and other fears, making a one-fits-all-approach impossible.

“While the pandemic has brought increased attention to the issue, loneliness is by no means a new topic.”

The various factors that can lead to loneliness show how complex an issue it is and how many interwoven forces are at play. The multitude of social, psychological, and political aspects also make clear that while the pandemic has brought increased attention to the issue, loneliness is by no means a new topic.

As was hinted at previously, the UK government already called out loneliness in 2018 as “one of the greatest public health challenges of our time” and responded to the rising numbers by establishing a commission, that has since become known as the Ministry of Loneliness. The ministry’s measures not only support large companies in dealing with loneliness at work, but also focus on creating new shared spaces and referring patients to community activities such as sports groups or cooking classes. Similarly, in 2019, the German Government published information on the effects of loneliness on public health, referring to several studies that show how much loneliness does not only affect our psyche but our whole body. According to these studies, loneliness does not only increase the risk of chronic stress and contribute to a rising rate of mental illness such as depression and anxiety disorders, but can also lead to serious physical illness, such as dementia or cardiovascular diseases. Loneliness is thus just as harmful as alcohol abuse or smoking.

In the past years, various governments and organizations have turned their attention to the issue of loneliness and launched campaigns on mental health and social bonding. Since 2020, many of these campaigns also take the pandemic and its special circumstances, such as isolation and restricted public life, into account. Since I started my research into this topic in Autumn 2020, many lists, articles, and documents have appeared and disappeared online as the pandemic continues and the issue of loneliness becomes more acute and new insights come to light. One of the first documents I found that is still online today, is a more general list on mental health during the pandemic provided by the World Health Organization. It contains advice such as keeping contact to other people, speaking about worries and fears, and developing routines. More recently, in February 2021, the campaign Zusammen gegen Corona (Together against Corona), launched by the German Federal Ministry of Health in 2020, published an article focusing specifically on loneliness. Called “Coping with Loneliness,” this guide contains more concrete suggestions, such as meeting online to play games, initiating shared projects such as reading clubs or learning a new language together, or refreshing memories via photos and diaries to create emotional closeness with others.

“There is still a difficulty, it appears, in taking into account the complex aspects that lead to loneliness in the first place.”

These new measures against loneliness in light of the COVID-19 pandemic show how much previous strategies against loneliness had relied on public life. Not having access to community spaces, not being able to meet in larger groups, not having face to face communications, has created a need to develop and design completely new approaches. Many of the proposed suggestions, however, still seem to mimic social settings or try to reactivate social contacts that existed prior to pandemic-related restrictions. There is still a difficulty, it appears, in taking into account the complex aspects that lead to loneliness in the first place. Aspects, which the pandemic has made even more acute.

Grateful for the raised awareness and the strategies that add to previous measures, I thus still find myself wondering: What about people who do not have social contacts or who find it difficult to reach out? What about people whose loneliness comes from a place other than missing social contact? Do these approaches show enough perspectives and include various enough realities? How can a conversation about loneliness be opened further? And how can the mentioned “new routines” look like? As a designer and an affected person alike I felt like there were a lot of aspects worth having another look at.

“Maybe there are other aspects of relationships and other forms of engagement that are worth looking at and designing new strategies from.”

At the age of 27, I am in the group most afflicted by the issue of loneliness and while my social environment before and during the pandemic includes a large number of people, I often feel that I do not belong. My feeling of loneliness is not an effect of isolation and limited social life, but of an insecurity and lack of trust that cannot be addressed by the simple act of making regular phone calls. It is a feeling of disconnection and of missing agency. Looking at this understanding of my own loneliness, I struggle to find myself in the provided methods. Reaching out is even harder than it already was, with spontaneous chatter or chance encounters happening only very rarely. I miss the physical presence of other people and the tiny surprises that make a day special, that distinguish one day from another. While in some parts of my newly arranged daily life, I wish to have more control, for others I yearn for less. I wonder whether there is something else missing than simply social contact. And I wonder what that “else” is. Between the actions possible during lockdown and the actions available in the long run, maybe there are other aspects of relationships and other forms of engagement that are worth looking at and designing new strategies from.

In search of approaches that would add to what is already provided—approaches that make use of other formats, diversify the perspectives, and come from subjective experiences and needs—, I reached out to friends and colleagues from different fields of aesthetic practice. I got in touch with performers, dancers, actresses, dramaturgs, media artists, scenographers, exhibition designers, product designers, communication designers, media philosophers, and writers. I asked them to build on past projects that engaged with questions of body, engagement and space, and their experience with formats such as playful exercises, collective practice, and performing arts. Deriving from their personal experience of loneliness and their specific practice, they engaged with the following questions:

What other notions of relationships could be approached?

Expanding the understanding from solely interpersonal relationships to an engagement with oneself, with other living beings, with the objects surrounding you, or with nature.

Can a strategy come from another place than the absence of something?

Working with what is already there and creating an awareness of its potential.

What forms can relational work take?

As playful rituals or humorous intervention that interweave organically with ones’ being and everyday life.

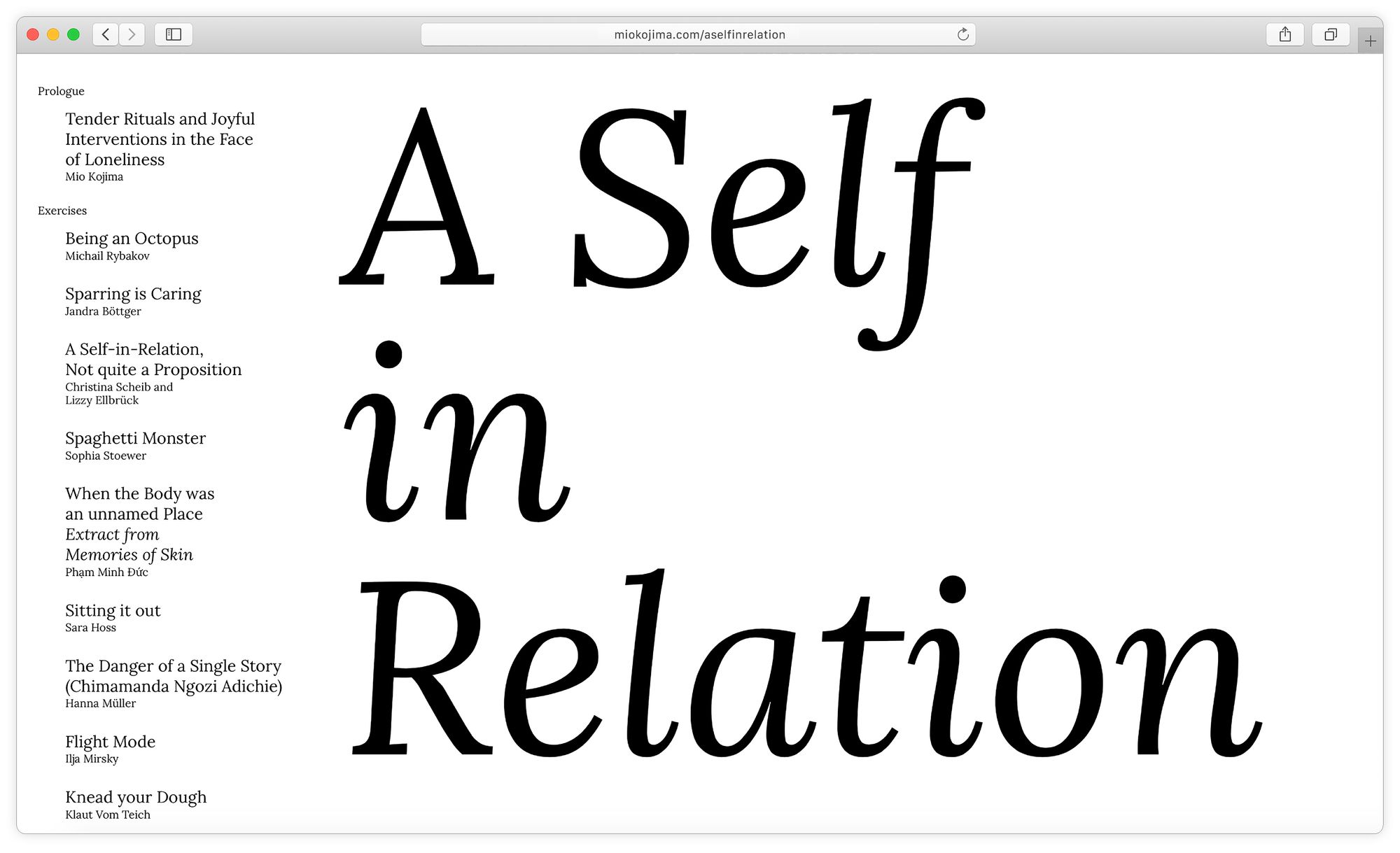

From this process, 19 approaches to conquering loneliness by entering into relationships and experiencing oneself emerged. They activate body and mind in different ways, from walking and boxing, to writing and listening. They are invitations to transform yourself into an octopus, to have a staring contest with yourself, or to mess around like a child. They ask you to get lost by, for instance, cleaning a very persistent stain or following a complete stranger. They conjure up memories, through smell, through using thumbs as memory-storage, or by taking a walk to visit sites of memory. Bodily borders are expanded and energy balls traced. Hands build shells, weigh objects, or grab spaghetti. Mirrors and smartphones reflect what is, could be, or has been.

Shifting in tone—from giving step by step introductions to telling a personal story, from poems to images, from tender to humorous—all the narratives, rituals, exercises, and interventions are designed to easily be done alone by oneself and at home without depending on any infrastructure, specific knowledge, or previous experience. They are an encouragement to playful experimentation and an invitation to interpretation and adaptation. They are shared in the hope of creating richer images of connectivity and opening new ways of tackling loneliness. And perhaps, they will even serve as an impulse to create strategies of our own.

Maybe, at the end, the current situation, precisely because of its shared challenges, is an opportunity to find solidarity and understanding of the issue of loneliness, to open up the discussion around it and overcome the stigma attached to it. And perhaps the experiences we make in doing so will inspire to counter loneliness not only in times of the pandemic, but also beyond.

Check out the 19 strategies here:

www.miokojima.com/aselfinrelation

Mio Kojima (they/them) is a German-Japanese designer and researcher. Growing up with different languages and cultures, Mio’s roots have led to personal explorations of language and meaging, and their connection to world-building. Mio is interested in forms of co-creating of knowledge and collaborative practices, looking especially at the infrastructures of “coming together.”

This text was produced as part of the Troublemakers Class of 2020 workshop.