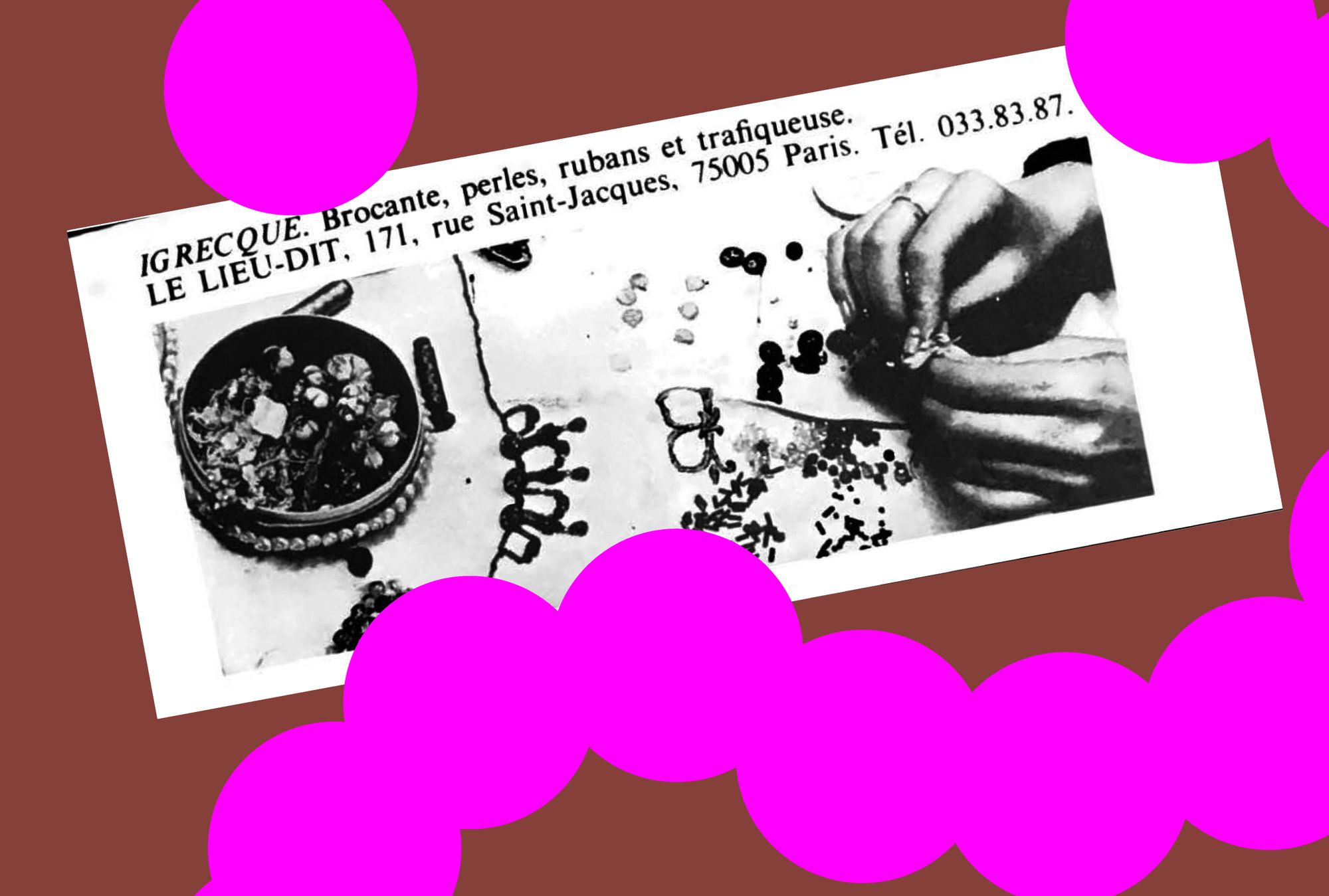

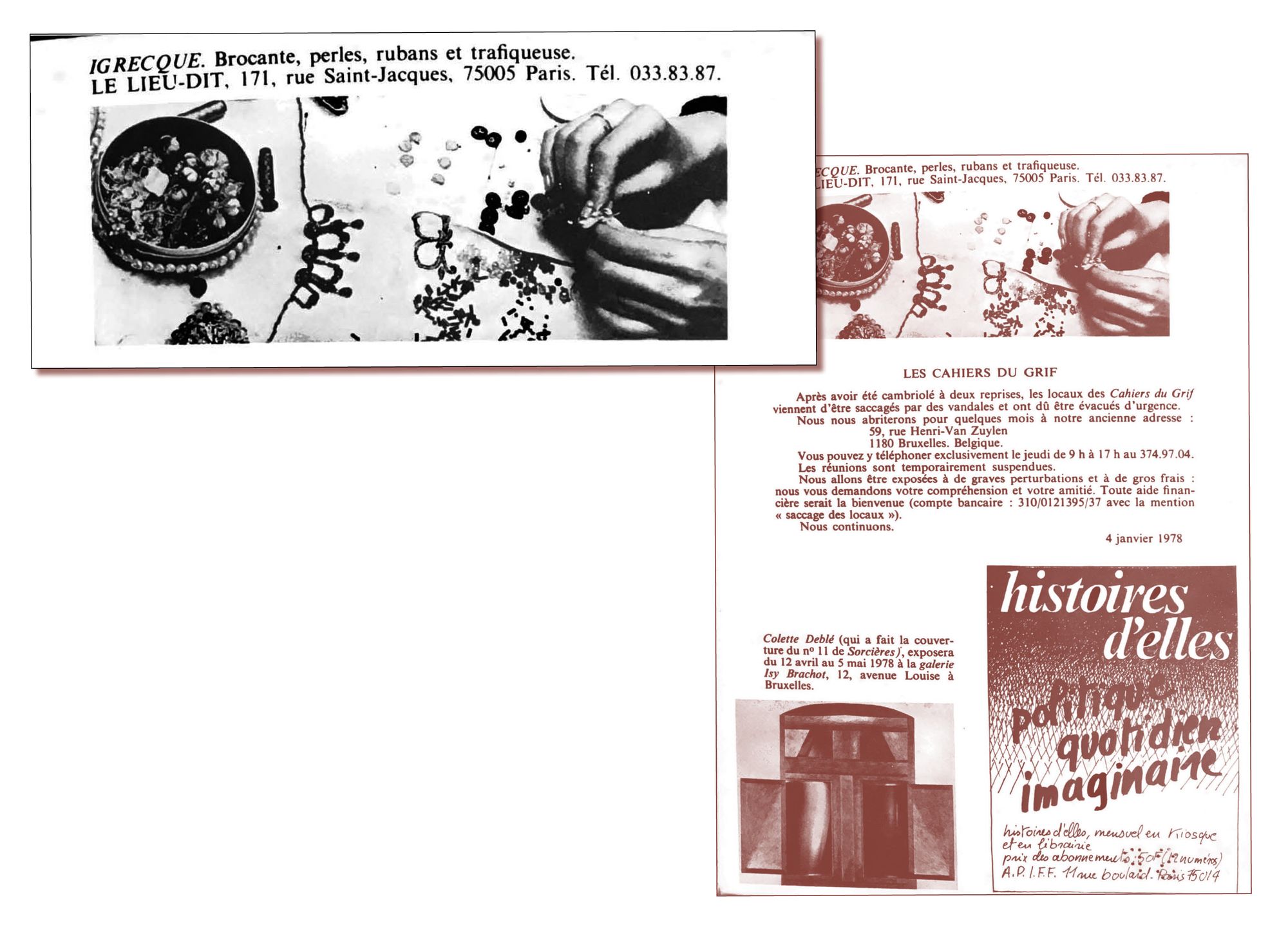

On the last page of the twelfth issue of the 70s French literary and feminist periodical Sorcières, there’s an advertisement for a feminist tearoom called Le Lieu-Dit. The word “lieu-dit” linguistically describes the name of a place that self-reflexively refers to some characteristic of that place. That vexing double-entendre in this tearoom’s name is in and of itself interesting. But it’s the advert’s caption —“Crafts, beads, ribbons, and a trafficker”—that really intrigues me. Who is the “trafficker”? What is she up to?

To “traffick” has two different meanings in French. First, like the English, it means to engage in illicit transactions—one could say, to participate in shady business—or to tamper with something. The second definition is harder to translate and has more “crafty” connotations; it refers to creating something in a bric-a-brac manner, for example, an art piece, especially one created at home. Le Lieu-Dit played with this double meaning: It was both a tearoom lined with traditionally feminine, domestic decor, and scrumptious cakes, and an underground literary and arts salon where women intellectuals dealt in subversive ideas and maybe even plotted some political acts.

“It was both a tearoom lined with traditionally feminine, domestic decor, and scrumptious cakes, and an underground literary and arts salon where women intellectuals dealt in subversive ideas and maybe even plotted some political acts.”

The charming yet mysterious tearoom opened its doors in 1976 at 171 rue Saint Jacques in Paris, close to the popular Sorbonne neighborhood. The former metal polishing workshop had been transformed by the feminist writer Yolaine Simha into a cozy café, library, gallery, and literary club dedicated to women and their artistic production. As Simha described in an interview for Le Monde, she filled the room with “tables strewn with flowers, tasty treats served in carefully selected dishes, and cultural activities.”

The advert for Le Lieu-Dit makes sense in Sorcières’ pages: It was a regular meeting-place for contributors to swap their ideas. Also, one of the magazine’s main contributors, known under the pseudonym Ygrecque, hosted regular readings and discussion groups at the tearoom—every day Tuesday through Saturday, in the afternoons and evenings. From 1978 onwards, Ygrecque also curated art exhibitions at Le Lieu-Dit. One of those exhibitions featured photographs of women diagnosed as hysterical in the nineteenth century. This was followed by an exhibition called Passeuses de Mémoire, in 1982, which centered on the relationships between grandmothers, mothers, and daughters. Simha archived the activities of her tearoom-meets-gallery in a “collaborative bookstore,” a.k.a. her slide library and collection of recordings of the events at the salon.

“Le Lieu-Dit is a place that has no official recognition but is known underground because it’s where something happens. This ‘something’ is an international network of women in the arts.”—Gloria Feman Orenstein

When art critic Gloria Feman Orenstein discovered the happenings taking place at Le Lieu-Dit in 1978, she enthusiastically described it to readers of the fifth issue of the Women Artists Newsletter: “Le Lieu-Dit is a place that has no official recognition but is known underground because it’s where something happens. This ‘something’ is an international network of women in the arts, whose Paris salon invites you to participate.”

The underground nature, which characterized Le Lieu-Dit, is inherent to the history of tearooms, an Anglo-Saxon tradition which, from the end of the nineteenth century onwards, enabled middle-class women to earn a living while gathering in spaces outside their homes. Sometimes, tearooms started in a house: Women began tearooms by “opening up a room in their home or setting up tables in their garden and offering tea and light meals,” as described by writer and former restaurant critic Cara Strickland in her article for JSTOR Daily, “The Top-Secret Feminist History of Tea Rooms.” In England, the suffragist movements of the early twentieth century had strong links to tearooms, which became, as Strickland writes, “hotbeds for women seeking systemic social change.” In Paris in the 70s, it was no different.

“[Simha] knowingly designed a homelike place, reproducing the codes of a reassuring and normalized femininity—food, flowers, and beads—in order to help finance her salon.”

Simha drew from the rich history of the tearoom. She knowingly designed a homelike place, reproducing the codes of a reassuring and normalized femininity—food, flowers, and beads—in order to help finance her salon. It was a place where ideas were trafficked. Where women’s artistic production was discussed, criticized, and taken seriously. Between “the carnations and the yoghurt,” as described in one 1982 Le Monde article on Le Lieu-Dit, this reconstituted domestic space allowed women to gather, to learn, to think, and to theorize. It was an artistic laboratory masking as—and making use of—domestic space, one featuring exhibitions, magazine meetings, and political readings, and one financed by the sale of pommes reinettes au yaourt et aux noix and tasty recipes for lemon curd brioche.

Fanny Maurel (she/her) is a designer with a master’s degree in design research from the University of Toulouse, Jean Jaurès in France. She’s interested in the power relations that make up and mesh the systems and objects of our society. She’s also interested in grimoires (a.k.a. spell books), speculums, bathroom scales, and diagrams.

This story is part of a project by Fanny Maurel that anaylzes the texts in the 1978 issue twelve of Sorcières, themed “Ranger/Déranger.”

This text was produced as part of the L.i.P. workshop, and has previously been published in the Feminist Findings zine.