A conference on design and politics serving pork sandwiches during breaks. A summer school on design and democracy charging exorbitant participant fees. A symposium on race and technology featuring zero Black speakers. A design school announcing job offers that pay in “fame and honor.” An established scholar being offered a salary, while an emerging activist is expected to speak for free. An event on decolonization taking place without a single gender-neutral bathroom. A cancelled event on feminism refusing to pay its speakers booked long in advance. A symposium on unlearning design choosing an ableist title. A journal about design and care initially being pitched with a one-month deadline.

Why is the design industry suddenly interested in care? Is “care” the new buzzword on the cusp of becoming a metaphor, like “decolonization?” Are we contorting design into this new shape because capitalism has found a way to monetize care? Is there a correlation between care becoming more prominent within design discourse, and the growing number of womxn and non-binary people entering the field? Is design now seen as a band-aid for the open sores of white supremacy, ableism, homomisia, transmisia, xenomisia and other forms of oppression?

“Care has remained surprisingly and revealingly absent from design. In this strange field we claim our own, the prevailing idea is that ‘care’ is reserved for those who are unable to care for themselves”

Critical thinking around care has a long feminist tradition. Almost forty years ago, psychologist Carol Gilligan formulated her famous and controversial notion of an “ethics of care” in women’s moral reasoning. Since then, many thinkers have joined the discussion, including Nel Noddings, Joan Tronto, Donna Haraway, Joanna Latimer, and others. All in all, care has been mobilized in many fields within the social sciences and humanities, as well as in other areas of intersection such as critical psychology, political theory, justice, citizenship, migration studies, business and economics, development, science and technology studies, disability studies, food politics, farming, and care for more than human worlds. But that care has remained surprisingly and revealingly absent from design. In this strange field we claim our own, the prevailing idea is that “care” is reserved for those who are unable to care for themselves: the infirm, the elderly, and children. At the same time, the limits of design’s imagination around care can be summed up in the recurring ideology of care as “women’s work”—echoed even in the original curatorial framework of the 2021 Porto Design Biennale.

“As a Black designer from Trinidad and Tobago and a white-passing Brazilian living in Switzerland, we constantly enact care when addressing certain seemingly polarizing topics such as ‘appropriation,’ ‘history,’ and ‘ignorance’—while being ‘mindful’ not to antagonize our often fragile, yet vocal white male European interlocutors.”

In their recent book The Care Manifesto, the London-based Care Collective exposes our unsettling “careless world” and “uncaring communities” to advocate the need for politics that prioritize care. They highlight how, historically, care and care work have been undermined and devalued, due largely to being associated with women, the feminine, and what was deemed “unproductive” care professions. As women, we have always been expected to perform acts of care for our families, partners, siblings, friends, and classmates—not to mention for random strangers commenting on our dress codes, or our expanding bodies during pregnancy. As a Black designer from Trinidad and Tobago and a white-passing Brazilian living in Switzerland, we constantly enact care when addressing certain seemingly polarizing topics such as “appropriation,” “history,” and “ignorance”—while being “mindful” not to antagonize our often fragile, yet vocal white male European interlocutors. Furthermore, throughout our education and careers, with few exceptions, care has materialized through a spectrum of carelessness and neglect. We’re exhausted by this rudimentary conjecture, but we know that we are not alone. Echoing the Care Collective, we believe care should be seen as a “social capacity and activity involving the nurturing of all that is necessary for the welfare and flourishing of life.” This means understanding our own vulnerabilities, and above all “recognizing and embracing our interdependencies.”

But has capitalism already found a way to profit from our interdependencies? “The system of care needs the receiver to stay at the receiving end, and the giver at the giving end,” explains Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung in his recent book The Delusions of Care. This gap in power and privilege is needed to maintain the status quo of capitalism and white supremacy, which thrives on individualism, thus simultaneously replacing our sense of community. Our neo-liberal societies now fail to care for each other—the poor, vulnerable and the weak. Governments and large corporations have opted for undermining care through austerity measures and prioritizing profits over people, resulting in the commodification of care. Covid-19 radically accentuated all preexisting inequalities and carelessness within existing structures, prompting a surge in literature around care during the last twelve months. Maybe this is also why design suddenly cares about care?

“Due to their Western modernist lineage, design institutions (as well as industries) have inherited practices, systems, knowledge and ways of knowing that are structurally violent and oppressive to many historically marginalized groups. To reclaim care, we believe that first and foremost, design needs to challenge its own violent past.”

In an interview with Cura magazine, Swiss artist Ramaya Tegegne speaks about institutions as “caretakers” that can provide care or harm, willingly or unwittingly. Due to their Western modernist lineage, design institutions (as well as industries) have inherited practices, systems, knowledge and ways of knowing that are structurally violent and oppressive to many historically marginalized groups. To reclaim care, we believe that first and foremost, design needs to challenge its own violent past. This would require, as Maria Puíg de la Bellacasa states in Matters of Care, “acknowledging poisons in the grounds that we inhabit, rather than expecting to find an outside alternative, untouched by trouble.” As explained by archaeologist Uzma Rizvi in her essay Decolonization as Care, once we recognize that we are placed in various systems in ways to keep us in place, “we stop and then slowly realign our ways of experience, our praxis experiences radical change.”

We started this article by listing a short compilation of recent lived situations and experiences of members of the Futuress community, including our own. They detail how design institutions such as museums, galleries, biennials, studios and schools attempt to tackle political topics such as feminism or decolonization—while systematically failing to do the work. We can’t help but feel a bit jaded: there seems to be a disconnect between the desire to publicly talk about equality and justice, and the ability to see how these issues materialize in the structures and practices we create as a design community. Due to precarious working conditions, lack of time, resources, infrastructure, payment inequality, lack of transparency, accountability, and overall epistemic ignorance so prevalent in the field, design sometimes inflicts more harm to the communities it wishes to elevate under the banner of “care.”

Let us be clear: care is not a magic pill that would heal the ills of design. Care is not a process to be developed, a method to be enacted, or a theory to be adapted, adopted or co-opted. Care is not a word that can be interjected as the next savior for the design field in the continued pursuit of capitalist dreams and ideals. We’ve killed all of our saviors, so let’s not kill care too. Instead, let’s look at care as an embodied experience, a continuous commitment and journey, one that should be frequently reviewed, revised and renewed to adjust to the needs of our changing communities and ecosystems. As positioned by Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung, care should “not just be a figure of speech, not just a metaphor nor analogy, but an undertaking.” In other words, care is what we actually do.

“Care is contracts signed and honored, fees paid on time, inclusive codes of conduct, complaint systems that work, acknowledgement of harm, genuine apologies and reparations.”

Care is consent, credit, and compensation. Care is contracts signed and honored, fees paid on time, inclusive codes of conduct, complaint systems that work, acknowledgement of harm, genuine apologies and reparations. Care is who we cite and who we refuse to cite. Care is refusal, and disengagement from toxicity. Care is also taking time off. Most of all, care is the willingness to do the work, and to do it better each time. Working with care therefore requires us to unpack what is actually done under the blanket category of care. We need to ask, on all levels of our practice: Who are we, and who do we care for? How do we create frameworks for care to thrive? How do we actually listen to those who have historically been silenced? How do we take them seriously, while accepting accountability and being the change we want to see in the world?

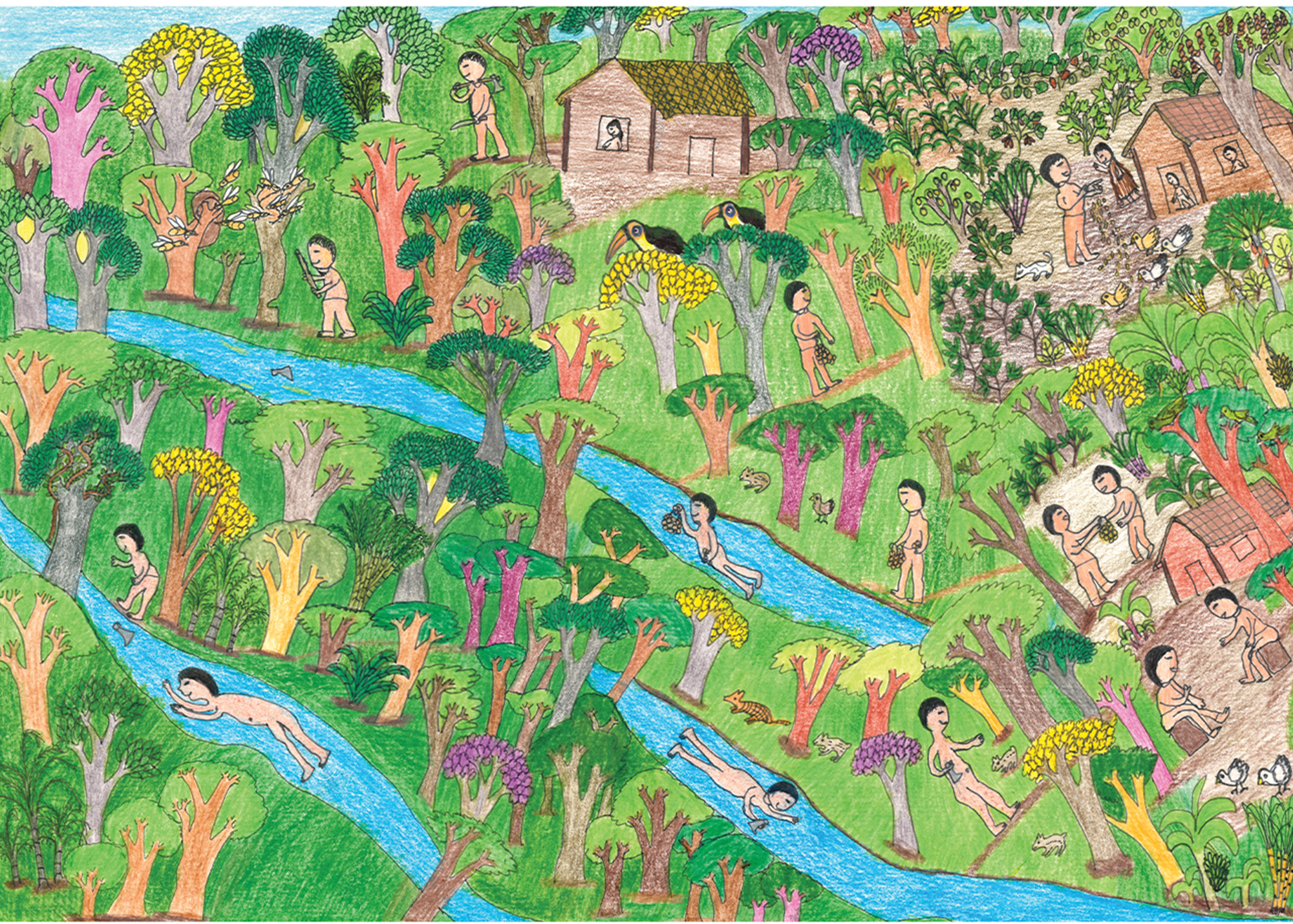

Most importantly, this burden of asking critical questions cannot solely be the responsibility of those who have been historically othered and sidelined, nor can it be the task of those who are relegated to do care work. To embrace care as an organizing principle in every part of life, we must do so collectively—as poignantly put by the Care Collective, to “elaborate a feminist, queer, antiracist and eco-socialist perspective, where care and care practices are understood as broadly as possible.” Care means learning from the knowledge that has been placed below the line of worthiness, and the groups that have been placed on the periphery of the global neocolonial capitalist agenda. It means elevating and amplifying the voices of the communities where care has been practiced and done, rather than only discussed or theorized.

Does design care? Maybe. Maybe design wants to care, but maybe it doesn’t yet know how. We are resolute in our stance that care cannot be a topic, nor can it be stabilized. As Maria Puíg de la Bellacasa says, we must resist categorizing care and instead “seek to emphasize its potential to disrupt the status quo.” Let us disrupt what care has traditionally been assigned to within design, and let care emerge better than how we found it. Let us embody care in design but also—and mostly—throughout our journeys in life.

Nina Paim (she/her) is a Brazilian designer, curator, and editor based in Porto. Her work spans exhibitions, workshops, and events, including Escola Aberta (Rio de Janeiro, 2012), Beyond Change (Basel, 2018), Department of Non-Binaries (Sharjah, 2018), Feminist Findings (Berlin, 2020), and, most recently, Etceteras: Feminist Festival of Publishing and Design (Porto, 2023). She has co-edited Taking a Line for a Walk (Spector Books, 2016), Design Struggles (Valiz, 2021), and Alter-Care (Esad-Idea, 2021). A three-time Swiss Design Award recipient, Nina has lectured internationally and her writing has been published by Occasional Papers (UK), Les Presses du Réel (FR), and the Korea Society of Typography (KR). In 2020, she co-founded the feminist platform Futuress.org, which she co-directed until 2023, when she launched Bikini Books, an independent publisher for design. In 2024, Nina was awarded an honorary doctorate from the London College of Communication at the University of the Arts London.

Cherrypye (she/her), a designer, writer, and marketing strategist from the Caribbean twin island of Trinidad and Tobago. A success story from a marginalized and impoverished community, her drive is to inspire other young people, especially girls, to achieve their dreams. Dearly departed from the corporate world of advertising, she is now flexing her design muscle as a visual communications specialist by combining artistic practice, business acumen, and storytelling traditions. A common thread in her design practice is creating Caribbean stories in an authentic Caribbean voice, respecting the past while looking to the future to sustain our stories, and using accessible formats to share these stories.

This text was originally written for the bilingual journal Alter-Care, edited by Futuress (Cherrypye and Nina Paim), on behalf of the Porto Design Biennale in cooperation with ESAD–IDEA. The 2021 edition of the Porto Design Biennale was titled Alter Realities: Designing the Present, and curated by Alastair-Fuad-Luke. Contributors to Alter-Care include Zoy Anastassakis, Marcos Martins, Keyna Eleison and Denilson Baniwa.

The title of this vertical, Complaint Collective, is an homage to Sara Ahmed, whose ideas have been and continue to be extremely influential to Futuress. In killjoy solidarity, we stand!