As we navigate multiple and entangled crises, the drive to make fashion—one of the largest industrial sectors—sustainable gains more and more traction. By the time of writing this article, there are 11,579,883 posts on Instagram using the hashtag #sustainablefashion, with a less industry-specific #sustainability hashtag not far behind with 9,290,917 posts. Academics, industry experts, and the media are increasingly calling out the myth of “sustainable fashion”—driven by the blame over fast fashion and their consumers, and the related response of conscious consumerist practices that dominate the narratives around the industry. The Covid-19 pandemic has only been barely destabilizing for the industry and impacted mainly garment workers, who suffered the short-term consequences of the unforeseen sudden consumption break. Despite being significantly affected by the reduced demand, the largest fashion companies such as the H&M Group, LVMH, Inditex, and Nike still reported profits in the billions, and the size of the global apparel industry is still estimated to be worth 1.5 trillion U.S. dollars.

“The overall feeling is that there is little agreement on what ‘sustainable fashion’ actually is—or can be—as part of a cohesive ecological project.”

Still, the overall feeling is that there is little agreement on what “sustainable fashion” actually is—or can be—as part of a cohesive ecological project. At the same time, there is a clear communication strategy that delineates a clear set of aesthetics and practices that encompass the vision of a sustainable fashion future within the industry. According to cultural anthropologist Kendral Thomas, who analyzed the discourses and practices of sustainability within the fashion industry, there is a tendency to privilege short-term, measurable improvements in line with business logics, despite the fact that on an individual level, managers had a discourse that envisioned radical change. Thomas establishes that this view on sustainability, driven by an industry perspective of fashion, differs to the one of designers—who, when addressing sustainability, focus on the craft: the making and the artistic aspects of it. This points to the commodification, and the ways in which clothes are massively produced, as the key problems in the industry.

As a trained fashion designer myself, I not only see the basis for these arguments, but I also recognize them as a core motivation to conduct my PhD research around these topics. There is a drive as a designer to want the clothes you make to last and be meaningful. In the daily routine of commercial fashion design work, I found little joy in mechanically and repeatedly making minor changes such as wash, buttons and seam to the same model of a pair of jeans just to create a novel product, or making something you know will only be purchased for anything other than affection—whether because it’s cheap and disposable, or because it’s expensive and therefore holds some elitist social value. But while Thomas finds these stances fundamentally contradict each other, I find that precisely this tension and the impossibilities of change it creates are what maintain the system’s status quo, making sustainable fashion seemingly sustainable.

“Both business managers and designers cling to the small ways in which they can contribute to change. However, in both cases, the individuals who are either employed or running a small business are dependent on recurring income, and therefore their own value relies on performing this labor on a regular basis.”

According to Thomas’s interviews, when designers talk about sustainability, they mention careful selection of durable materials and an atemporal design, even though they create new designs daily. As individuals and actors within the industry, both business managers and designers cling to the small ways in which they can contribute to change. However, in both cases, the individuals who are either employed or running a small business are dependent on recurring income, and therefore their own value relies on performing this labor on a regular basis. Her article concludes by pointing out that the very definition of sustainability cannot be resolved by industry actors, who are stumbling with their own contradictions, leaving consumers to pick up the pieces and figure out how to enact sustainability similarly as individuals. Moreover, as all wearers of clothes are placed within this category of “consumers,” which defines the borders of their experience and participation in the system, it hinders the possibilities of including them as active actors in a broader cycle of sustainability with all stakeholders.

Sustainable Fashion looks like this (spoiler: it’s very basic)

A quick search through the trend forecasting company WGSN for the word sustainability gives a very clear picture of how sustainability looks, as well as how it can be applied to products and communicated by brands. A similar search on any image-focused social media such as Instagram, Pinterest or TikTok confirms that those practices are predominant in all sectors of the fashion industry.

There is a well-defined color palette adopted to communicate sustainability—composed of shades of brown, beige, blue, and green to establish a visual connection to nature by mimicking unbleached or naturally dyed fibers (see here and here). In the same line of having a trimmed color palette, from a formal perspective of garment designs, there is, as aforementioned in Thomas’s paper, a growing trend of favoring simple shapes and achieving an “atemporal design.” The same applies to materials as the narrative around them increasingly implies some inherent sustainable condition by pointing to a connection to nature, for plant-based or cellulosic fibers, or highlighting functionality, in the case of synthetic fibers. This minimalist trend is sustained by a discourse against the speed of constant new fashion trends, with the intention that the neutrality of their designs will outlive more fashionable and therefore ephemeral designs.

Again, as fashion workers (encompassing a variety of actors such as managers, fashion designers, pattern makers, garment workers etc.) rely on their labor, this intention doesn’t expressively translate into an actual change in the number of items designed or the speed of production, which culminates in a progression of these items, marketed as “elevated basics” or “bold minimal.” On the other end of the spectrum, there are many sustainable fashion tactics that have become popular amongst consumers that converse with the proposed neutrality of materials, colors and shapes by the industry, such as the capsule wardrobe or the 33 items challenge (which was later trademarked to Project 333). The general idea is to edit your wardrobe down to a minimalist selection of pieces, preferably the ones that resonate values such as quality over quantity, and invest in pieces that will last, which may lead to a reduced consumption, or periods of “shopping fasts.” The pieces should easily match each other and therefore the shapes, materials and the color palette must also follow those descriptors. These curated wardrobes are composed of pieces that are also described by consumers as “essentials,” “basics,” “classics” and “neutral,” reproducing the industry’s narrative.

The future is basic too

“Atemporality” means they can last forever, both in terms of material quality as well as a formal notion of style, indicating that there is a collective imaginary of what “the future” looks like in terms of clothing. There is an accepted notion that clothing has linearly developed over history to become more democratic and practical. People went from differentiating themselves from lower classes by wearing cage crinolines, to everyone being able to afford comfort in a black turtleneck, blue jeans and trainers, the discreet but powerful uniform worn daily by the late Apple co-founder, chairman, and CEO, Steve Jobs—now the ultimate dress code for success. Moreover, it is a common opinion that this development is a good thing. At a first glance, how could it not be? Fashion’s frivolous and ephemeral aesthetics are giving way to science-based, practical sustainable clothes, and, in any reasonable future, all of us—similar to Steve Jobs—simply won’t have to worry about it anymore.

“When looking into these [sci-fi film] productions, it is highly visible that only in depictions of extremely unequal societies at the brink of collapse, or in dystopian scenarios, there is a display of very ubiquitous and ornamental rich fashions.”

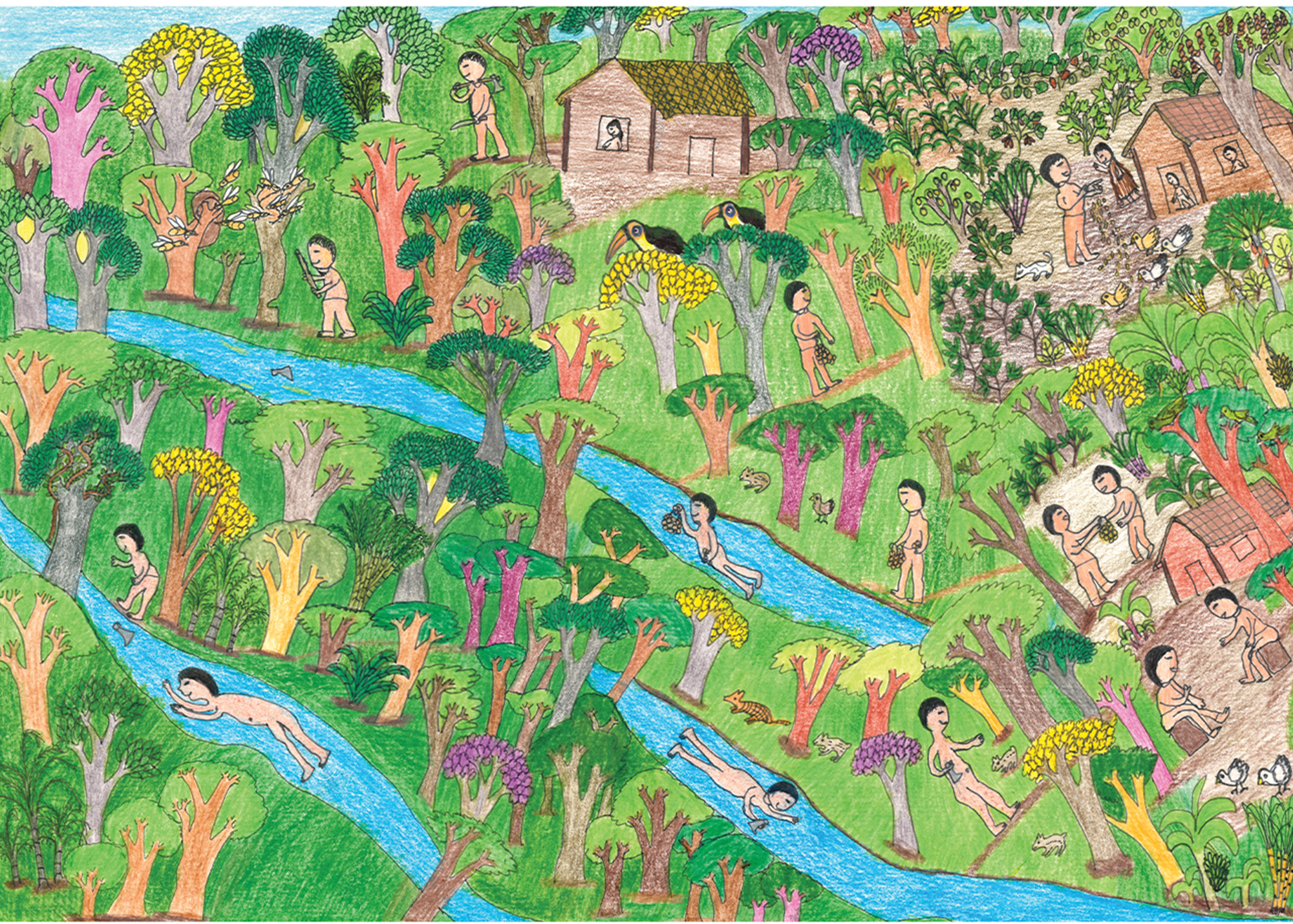

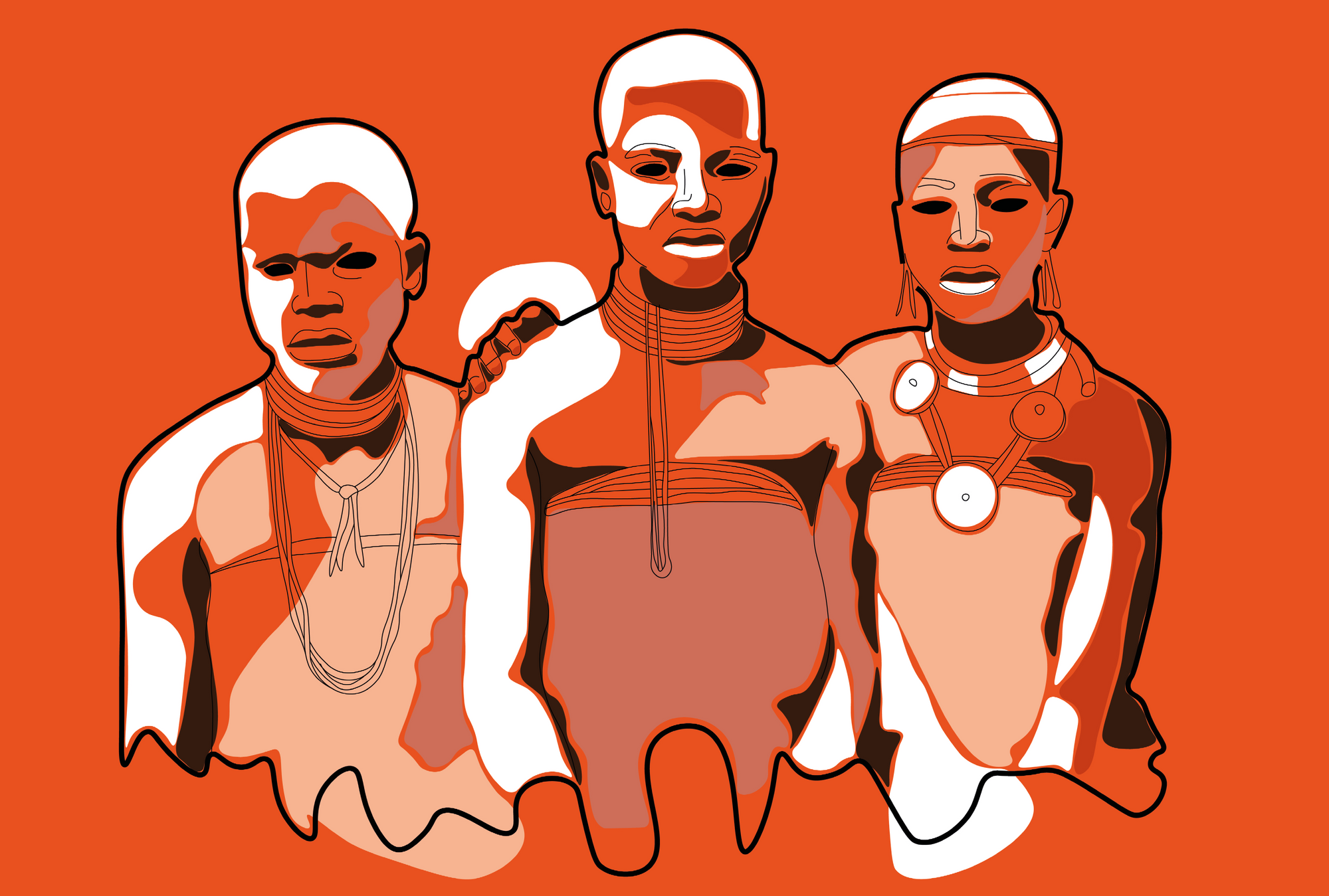

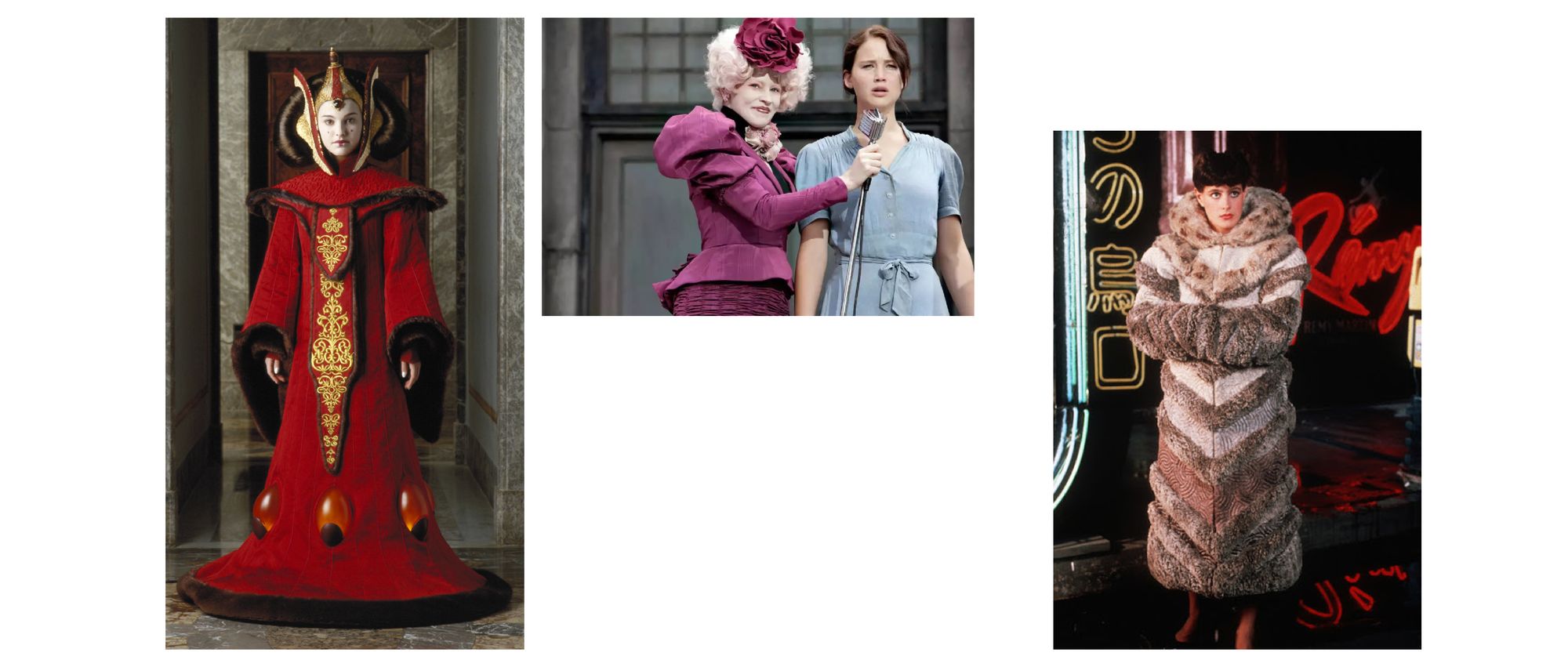

These notions are widely accepted, being reflected by and reproduced in sci-fi film productions which help to fuel the public imagination about the future of fashion. When looking into these productions, it is highly visible that only in depictions of extremely unequal societies at the brink of collapse, or in dystopian scenarios, there is a display of very ubiquitous and ornamental rich fashions. Additionally, more than often, this is done by appropriating non-Western and indigenous dress. For example, the gowns worn by princess Amidala in the Star Wars prequels—a direct reference to Mongolian royalty dress, which aligns well within the overall Orientalist look of the franchise—are used as a symbol of the frivolity and naivety of a character who is a female senator completely unaware of the harsh realities at the peripheries of the galaxy, and doesn’t foresee the imminent collapse of the republic she serves being orchestrated around her.

Another well known example is the Hunger Games trilogy, which portray the wealthy citizens of the fictional Capitol as an outlandish baroque-like caricature, dressed distinctively different from those who live in the other marginal districts, who dress more frugally and in washed-out colours to depict a dirty, downtrodden existence in which they have to make do with what they have. These serve to amplify the social relations of class and existing contradictions of fashion and “commodity fetishism” in our society today.

There are also interesting examples that portray the collapse of opulent, maximalist societies in mainstream sci-fi, particularly within the subgenre of cyberpunk, where the future portrays a combination of low-life and high-tech, drawing from narratives of post-apocalyptic dystopias. The main example of this genre is Blade Runner, which is set in a rundown, highly urban scenario, covered with neon signage in Asian alphabets and gritty alleys with noodle bars. The notion of “Cool Japan” and references to its fast technological developments in areas of robotics and cybernetics, coupled with a hyper-consumerist non-U.S. American capitalist society, are common motifs to build these dystopian, techno-orientalist worlds.

In futures presented as preferable, however, the aesthetics are very different. Uniforms or clothes that embody principles of uniformity with characteristics such as practicality, functionality, sobriety and rationality are a common choice of costume. Of course uniforms also evoke a strong sense of militarization and authoritarian futurism. In the original trilogy of Star Wars, the fascist empire that took the place of the former republic dressed everyone in monochromatic tones to show their lack of individuality—both that of their oppressed underclass, and of its military.

The theme of collective oppression is also well explored with the Star Trek Voyager character Seven of Nine. Seven was born human, but was transformed into a drone as a child when she was assimilated by the Borg, an antagonist alien society that embodies the very common trope of an all-conquering technological society that has evolved past the need for individuality and emotions. They forcibly assimilate other beings into their “Collective,” which strives for a continuous search for computationally calculated perfection. Seven of Nine is stripped of all her individuality and is dressed in a catsuit with cyborg implants, which is typical in depictions of female cyborgs.

Even though some depictions of uniforms carry a bad reputation, there is a tendency in sci-fi to depict a hope for synthesis, and a human collectivism which results from progress. According to Science Fiction scholar Darko Suvin, progress or evolution in these cases are distorted to mean “a condition of relative complexity to one of relative uniformity” instead of “a gradual change from a condition of relative uniformity to one of relative complexity” to favor a bourgeois liberal notion of progress. This more accepted notion of uniformity is seen in the many variations of the Star Trek United Federation of Planet uniforms, which are made to fit each crew member with a replicator—machines that are capable of fabricating anything from food to clothes and spaceship pieces from a molecular level, much like how we imagine the evolution of 3D printers.

Another classic example is, of course, Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey, which shows outfits that are pristine with perfectly sharp cuts, block colors, no buttons, and mostly composed of the (then recently invented) synthetic fibers.

The costumes of the 1968 sci-fi classic were designed by British designer Sir Hardy Amies, who was famously also at the time a Royal designer to Queen Elizabeth II. At first, it seems to be an odd choice to choose someone so tied to a very conservative institution such as the British monarchy to envision the fashions of an intergalactic future, but it is a strong symbolic choice that represents the development trajectories shaped by and after a Eurocentric understanding of modernity and its colonial project. Aimes is known for stating that women shouldn’t become designers because they lack objectivity and can only design clothes that fit themselves best, whereas men designers know what is best for everyone. In the same interview, he says he believed his elegant suits to be “very English.” This opinion is shared by Austrian architect Adolf Loos, who viewed English suits as a symbol of Western supremacy, indicating both distinction and belonging. Loos actively encouraged his Jewish clients to wear English suits as a way to better assimilate into Viennese society. He linked “ornaments”—not only in buildings, but also with regard to furniture and dress—to crime, degeneracy and femininity, adding that ornaments were something they have conquered and thus, have surpassed the need for decoration. Ultimately, he saw the removal of ornaments as a symbol of cultural evolution. Anthropologist Minh-Hà T. Phạm describes clothing as a technology that makes hierarchies visible, and states that it was fundamental to the development of human classification and Western epistemologies of race. Particularly tight clothing was a marker of hygiene and mental stability, whereas loose garments were an indication of madness and a key element in orientalist fantasies.

“Max Weber describes how decorative superfluities and ostentation were considered sinful, especially when it came to personal clothing, and that this value placed on uniformity was fundamental to standardization of industrial production in capitalist society.”

This thread between futurism, uniforms and uniformity is deeply connected to the understanding of the birth of fashion being tied to the industrial revolution. In his famous work The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Max Weber describes how decorative superfluities and ostentation were considered sinful, especially when it came to personal clothing, and that this value placed on uniformity was fundamental to standardization of industrial production in capitalist society.

The main modernist movements—Italian Futurism, French surrealism, Russian constructivism, and the German Bauhaus—also valued sleek minimal design and functionality. Later on, designer Dieter Rams consolidated these principles in his famous speech where he laid out 10 principles for good design. The book Fashion Victims by Alison Matthews David demonstrates how modernity was also characterized by stripping men’s fashions of any unnecessary adornment, and the use of dark sober colors and the lack of ornamentation made it a stronger marker for binary gender differences, Western democracy, rationality, and technological progress. In contrast, women (both consumers and garment workers) were placed as being naturally fashion victims, irrationally drawn to the frivolity of clothes. While men got to distance themselves from being the victims of fashion, they still owned and profited from its business by developing the materials and running the manufactories. To this day, the richest and most powerful people in the industry are men, but whenever we look at who is to blame for the unsustainability of the industry and what needs to be “fixed,” we find female consumers with their irrational desires for ornamental fashion.

Is fashion even a thing anymore?

This sleek future, with fashion being stripped of adornment and meaning, is a direction that has been exposed in 2015 when trend forecaster Li Edelkoort officially declared the end of fashion, giving way to an era and industry of “clothes” instead. According to her, her manifesto was positively received by industry actors and didn’t receive any strong criticism. Almost six years later, the statement seemingly hasn’t had any significant impacts in the industry either, and that might be precisely the point. It resonates directly with the famous statement by political economist Francis Fukuyama right after the fall of the Soviet Union, in which he announced the “end of history,” meaning that society was heading in the direction of a universal order of liberal capitalist ideology. This premise was never meant to be understood as the end of historical events, but of challenging ideas and alternatives. Similarly, when we reflect on Edelkoort’s manifesto, we see that the declaration of an “end” was more about continuity, rather than a disruption.

“From that perspective, the massive production of garments [...] and its distribution within a wide range of prices is fundamental to ensure that fashion is democratized, and that everyone can exercise their ever-evolving individuality [...]. This is where the main contradiction lies, as it is clear that mass production of clothes heavily depends on standardization.”

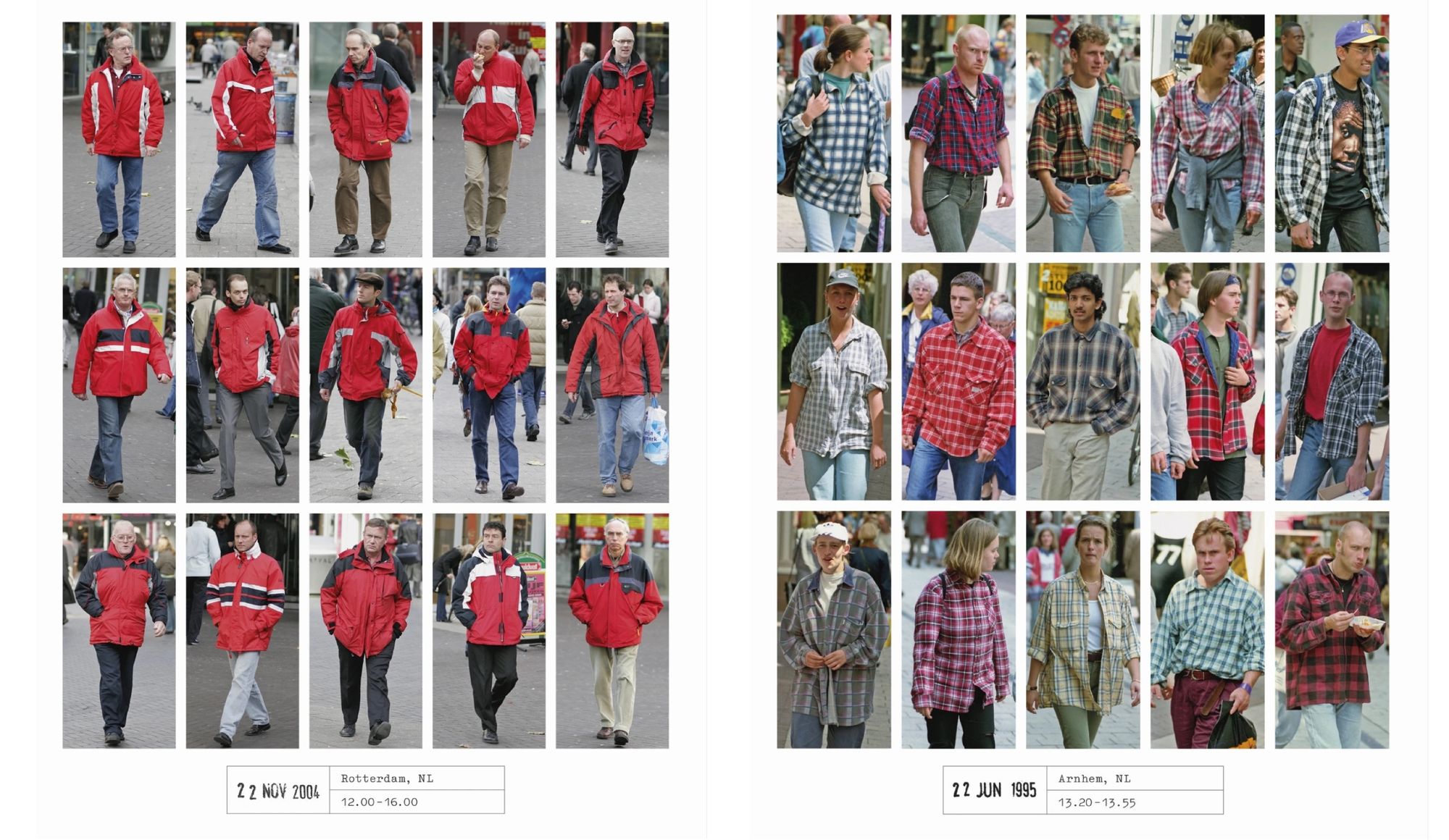

Mass industrial production of clothes continues to operate as usual, traditional fashion calendars remain intact, and it is unlikely that the system will fundamentally change from this point forward. Still, the fact that Edelkoort wasn’t criticized for her provocation does not mean that there is no resistance from sectors of industrial fashion or consumers. Another very common assumption is that sustainability practices or minimalism impose restraints on designers’ creative processes and consumers’ desires to differentiate themselves and feel unique. From that perspective, the massive production of garments made possible by the constant industrial production of clothes and its distribution within a wide range of prices is fundamental to ensure that fashion is democratized, and that everyone can exercise their ever-evolving individuality through readymade clothing. This is where the main contradiction lies, as it is clear that mass production of clothes heavily depends on standardization. This is well visually documented by photographer Hans Eijkelboom in his book People of the Twenty-First Century, which constructs a very insightful panorama of contemporary fashion consumer culture.

There is a distorted notion that style and individual adornments are the cause of what is costly to the planet, and that sacrificing meaningless ornaments is the way to tackle unsustainability. This conception of fashion is rooted in one of the earliest writings in fashion scholarship by sociologist Georg Simmel, who in 1905 observed the changing styles as a central feature of fashion, in contrast with “non-fashion” systems that were constrained by tradition. Anthropologist Sandra Niessen makes the argument that this definition of fashion supports the image of the European subject as one capable of evolving, and is an act of assimilation via a sartorial episteme. In that sense, we can conclude that as a hegemonic project, and with the support of modernist movements, fashion has been successful in its assimilation efforts and can finally now rest in peace. The overall vision of sustainable fashion further solidifies the requirements of fashion’s death as it presents a project of consistent improvements to the standardization methods of producing clothes (waste reduction, water usage, closing loops) and better clothes (with long lasting materials and trend-proof designs). Sleek and well-designed minimalism then comes dressed as a middle ground of aesthetic compromise, but ultimately this reduction of fashion into clothes, and materials into their technical properties, only produces what Paul Preciado calls a “prêt-à-porter solution.”

Still, while fashion is a technology that can be used to marginalize groups and individuals, stripping clothes of fashion, meaning and ornamentation as a principle is also undeniably rooted in supremacist, colonial and capitalist ideals—systems that are directly linked to the current ecological crisis. Hence, from a strategic perspective, neutralizing fashion cannot resolve the contradictions of the fashion system, and is not an effective solution to imagine better socio-ecological futures. Instead, we need to deconstruct this belief that in a future democratic and advanced society, there is no place for the superficial frivolities that fashion carries.

There is no are alternatives

But the question remains about what alternatives we have and how to create them, and the answers many times can evoke feelings of hopelessness, being impossible to imagine different futures. Brazilian educator and philosopher Paulo Freire thought that hope is an ontological necessity, and even dedicated an entire book to explore this, titled Pedagogy of Hope. In this book, Freire identifies hopelessness as something unnatural to human beings, being a designed authoritarian force that denies dreams and utopias, thus blocking the emergence of what he calls “untested feasibility” (inédito viável), a concept that embraces the belief in transformation. Hope, for Freire, can be learned and enacted through a process of critical conscientization. Hope is not static, it requires movement and action, being characterized by cognitive intentionality, ontological assertion and anticipatory consciousness—categories that affirm humans as historical beings and actors in the construction of realities and the forms of knowledge required for transformation. Such understanding of hope as a way to reflect on the concrete material conditions of reality is a way of inciting epistemological curiosity (another term borrowed from Freire), thus being a powerful tool in overcoming this imaginative block.

“A decolonial approach to sustainability is important to reclaim, imagine and establish a more relational connection to clothes, textiles, resources and even beauty.”

Decolonial fashion theories also help to bring out and examine these contradictions in order to challenge the limits of the hegemonic Western concept of “uni-versal” presenting a “pluri-versal” alternative to the former. Fashion scholar and educator Tanveer Ahmed uses the sari as a prop with her Fashion Design students at the Royal College or Art in London to disrupt the limits of the Western concept of fashion by proposing a theoretical-practical exercise that revealed different forms of material knowledge and ideation processes—thus foregrounding fashion as a pluriversal practice, “comprising multiple ways of dressing bodies.” In a similar manner, a decolonial approach to sustainability is important to reclaim, imagine and establish a more relational connection to clothes, textiles, resources and even beauty.

The contemporary reframing of minimalist fashion is, I believe, a symptom of the post-politics scenario in which we live. With the spirit of The End of the End of History, I wish to push for the end of the end of fashion as a way to bring meaning and therefore politics back into the materiality of our clothes, and seize the prospective possibilities of plural fashion futures. Instead of further detaching ourselves from material meaning in favor of universal technical functionality, this approach is one that values the generative potential of materialities. It can pose a different path to the degrowth of industrial fashion, and expand the limits of fashion consumption to emancipatory sartorial practices. I believe that we should focus on leveraging the effects, memories and experiences to create novel ways of accessing and engaging with tacit knowledge to actively participate in the construction of new fashion futures.

Carmem Saito (she/her) is a designer and researcher whose multidisciplinary practice engages fashion and UX/UI design. She is currently a PhD researcher at the Royal College of Art in London. Her ongoing work “Touch and Motion of Reality” examines online fashion shopping, aiming to redesign the technologies and apparatuses that currently support practices of consumerism by proposing a framework that centres tacit material knowledge to devise new ways of mediating touch and affect to avail more subjective aspects of textiles to be experienced digitally. Her interests are in exploring the complexities and contradictions of fashion in global and digital contexts, with a specific focus on the sensing body, touch and materiality. She holds a BA in Fashion Design from Faculdade Santa Marcelina, (São Paulo, Brazil), and an MA in Integrated Design from the Hochschule für Künste Bremen (Germany).

This text was produced as part of the Against the Grain workshop.