In 2018, Gucci caused a massive media uproar across the fashion industry. The luxury Italian brand’s Autumn/Winter collection presented several items on the runway that were exact copies of Sikh religious head coverings—available to purchase for $790. Despite cultural appropriation being called out continuously across news outlets and social media, not much seems to change. Reflecting on the Gucci controversy, creative strategist Anu Lingala asks: is it true ignorance, or is there more to it? She highlights a design practice that may be partly responsible for such a lack of cultural sensitivity: the mood board.

Making a mood board is a widespread practice to start off a design process. You want to figure out the visual language and conceptual inspiration for a new project, so you pull a few images from online searches, art magazines, and specialized archives. As you play around, arranging images next to each other, you start getting a sense of the project’s possible direction—whether it’s a lamp, a fashion campaign, or a book. As a digital or physical document with little to no words, the mood board can contain photographs, patterns, color swatches, and material samples. It is often used as a visual proposal in response to a design brief and serves as a point of reference for members of a design team, their clients, and the project’s stakeholders to support the development of ideas through a continuous process of selecting, collecting, and juxtaposing. However, as Lingala argues, by assembling visual references in this way, the mood board divorces an image from its context and, thus, its cultural meaning.

“Mood boards are susceptible to cultural appropriation, co-option, plagiarism, and the reproduction of oppression.”

The shifting of contexts and meaning is inherent in mood boards. In the process of combining references from the past—near or distant—to develop upcoming projects, this shift can happen through extractive processes such as using images without acknowledging their cultural context, a lack of heterogeneous references, and the absence of analysis. Because of its omnipresence, creative practitioners and design educators often overlook the mood board’s significance to design projects. This negligence undermines responsibilities in appropriately sourcing, crediting, and recontextualizing visual references that inspire the creation of new products. Consequently, mood boards are susceptible to cultural appropriation, co-option, plagiarism, and the reproduction of oppression.

However, if done in a sensitive way to account for the designer’s positionality and biases, as well as hierarchies between dominant and marginalized viewpoints, there lies a subversive power in the creation of mood boards. When used in this way, they can challenge the reproduction of past and present oppressive systems through providing paths to reflect on whose needs are addressed, whose futures are built, and whose perspectives could be brought to the process through collaboration. Reflecting on what needs to be changed in design practices, Lingala asks: “Should mood boards include citations or references to ensure meanings don’t get lost?”

Mood Boards and the Politics of Citation

Just like the use of citations with academic writing, a mood board weaves together references from various historical backgrounds in the proposal of a new idea. In her blog post “Making Feminist Points” and her book Living a Feminist Life, feminist theorist Sara Ahmed discusses the politics of citation in academia. She highlights how academic disciplines revolve around a citational structure that reproduces white patriarchy. Researchers tend to repeatedly cite the dominant voices in their fields—often white, cis-male scholars in well-established academic institutions. Perpetuating a hierarchy of certain viewpoints over others, what Ahmed discusses as a “citational chain” roots the making of new ideas in the institution of white maleness.

Similar citational structures can be found in design processes. This encourages design students and professionals to develop their practice in reference to a limited canon—a canon that is reproduced in theoretical texts, but also across different visual communication tools such as mood boards. To Ahmed, such citational structures work as a selection technique that determines who will—and who won’t—be visible and recognized as valuable references to future projects. Following Ahmed’s argument, as design practitioners, we should also question how we search, select, and use past images to inspire our developing creative ideas. Thus, when working with visual tools like a mood board, the designer is accountable for considering how it projects, acknowledges, and contextualizes diverse cultural histories into the future.

The key concern with mood boards is that they allow designers to present existing images in new combinations as innovative ideas without necessarily engaging with the visual references’ original contexts. In fact, it is common practice to feature images on a mood board without crediting their sources. This not only obscures the histories and cultural meanings of visual references, but it also reinforces domination over the source of inspiration. By recontextualizing Sikh head coverings into a new design by Gucci, the mood board can reassert the power of a multi-billion dollar European luxury brand to profit from extracting cultural resources—with no credit or redistribution of the benefits gained.

“Key to the designer’s creativity is the heterogeneity of the visual references and thus the originality of the connections made.”

The main issue with Gucci’s product is that it is a mere reproduction of Sikh head coverings rather than a culturally informed and power-sensitive use of the references. Lingala accuses the mood board because it is where sources of inspiration are generated. However, the academic literature on mood boards argues that a specificity of the mood board practice is to combine references from different disciplines, cultures, and points in history to offer original creative ideas. Images from 10 years ago meet 100-year-old images; images from East Asia land next to South American images; images of jewelry enter in conversation with images of pastries. Therefore, key to the designer’s creativity is the heterogeneity of the visual references and thus the originality of the connections made. In this sense, a mood board opens a conversation between images that may initially seem unrelated.

With regard to the politics of use, however, this means questioning how and why these references are employed. Who feels entitled to use another culture as inspiration and reconfigure it? What are the power dynamics at play here?

Controversy and Creative Secrecy

What has possibly been missing on Gucci’s mood board is further consideration of the references’ original context in relation to the intended end product and its use. In academic writing, citations situate one’s ideas in conversation with previously published ideas. However, in the creative industries, for the sake of creative authorship, there is frequently a lack of recognition given to the works that inspire new ideas. Essentially, we may never know what exactly was on Gucci’s mood board—or any other brand’s— because mood boards are rarely shared publicly, and are usually discarded once a project is over. This is rarely a matter of storage. Rather, since a mood board documents the visual research that influenced an idea’s development, it bears evidence of its originality (or lack thereof)—evidence that many may prefer to keep private. In a way, discarding a mood board after a project’s production is akin to deleting a bibliography when publishing an essay; nevertheless, the design industry largely considers mood boards to be confidential—a creative secrecy that only further obscures its politics of use.

“Where does authorship begin? Is a bibliography—or a set of visual references—intellectual property? ”

There are, however, a few instances when a mood board may be circulated publicly. In 2019, stylist and creative director Kyo Jino sued over an intellectual property claim concerning pop singer Aya Nakamura’s music video “Pookie.” He had initially pitched his ideas for the video with a mood board but was not hired for the job, and later claimed that his ideas had been used although he was not part of the video’s production. Jino lost the trial—the court concluded that even though there are similarities, the final styling is different from the images on the mood board. Yet a mood board juxtaposes images to engage in a creative analysis of existing references—not a reproduction of the original images. This is similar to someone pitching an academic paper with a bibliography to reviewers; then, after the pitch isn’t approved, another paper is later published by one of the reviewers using the exact same references. This raises the question: where does authorship begin? Is a bibliography—or a set of visual references—intellectual property? The crux of the issue is not about how something is cited, but about to whom the citation belongs.

Another well-known controversy is the leaked mood board for Ariana Grande’s costumes for her 2019 tour, intersecting accusations of both appropriation and plagiarism. Journalists and fashion bloggers who accessed the document noted that among the references used for Ariana’s style, a vast majority were images of Rihanna and other women of color, thus accusing the creative team of “blackfishing.” Another costume from the tour was a near copy of work by Chinese-American designer Creepy Yeha, whose images were heavily featured on the mood board though she was not involved in the design of the costume. Once again, the lack of heterogeneity in the mood board resulted in copied looks.

This highlights the responsibilities in recontextualising visual references. A mood board must take into account the context of the project, its end product, and its user. Imagine a scenario whereby a white academic refers mostly to ideas from authors of color—but doesn’t credit them. In this case, the way they draw on other people’s work can be confused for their own ideas, and a lack of reflection on the author’s positionality raises questions regarding their understanding of power relations in the field.

The examples from Gucci’s cultural appropriation, Kyo Jino’s court case, and Ariana Grande’s tour costumes highlight the politics at play when working with mood boards. Mood boards are not hermetic to oppressive systems, and are responsible for the reproduction of “White-Supremacist Capitalist Patriarchal” power dynamics—to use bell hooks’ term. The role of mood boards must therefore be seriously reconsidered, as it bears significant influence on design education and the creative industries.

I’ve been researching the politics of referencing in mood boards over the past three years, doing workshops across universities and cultural institutions in the UK and Western Europe. I always start my workshops by asking participants if they know what a mood board is—most often, they all do. Then I ask if they had ever been given guidance during their previous education on how to make a mood board and what it means to do so—usually, there are barely two or three hands up.

“If we approach the mood board as a citational practice, we can review how we cite and engage with our visual references.”

Beyond a method for inspiration, the mood board should support creatives to rework references of the past, conventions of the present, and ways of orienting ourselves towards the future. If we approach the mood board as a citational practice, we can review how we cite and engage with our visual references. To challenge traditions of citational structures, Sara Ahmed suggests a feminist practice of citation—a practice of feminist memory that uses citations to make the works of those who came before us known. In a similar vein, a feminist citational practice can be applied to mood boards as well. This could consist of implementing a more in-depth research process, the reflective analysis of biases and limitations in our image collections, the consideration of positionality and the context in which the project’s outcome will be used, and transparent image citations with coherent referencing systems.

Suggestions for feminist citational practices in mood boards

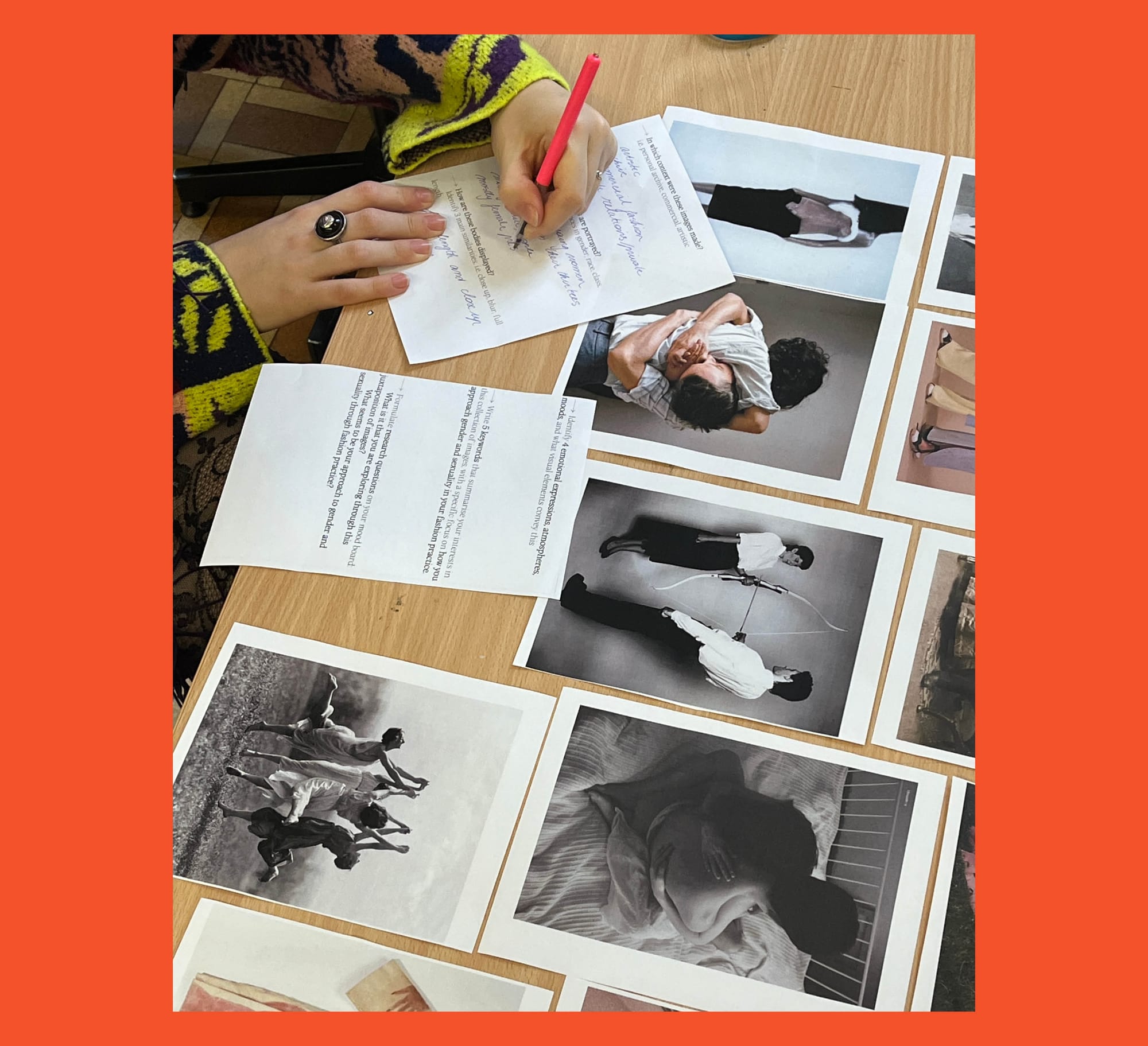

Throughout my workshops, I started testing feminist citational practices with mood boards. Although rather centered around the classroom, all approaches can be applied to professional practice and the making of a mood board in any creative context.

Expanding: Beyond your search engines’ first and easy finds

A feminist practice of visual referencing seeks to center works beyond the superstar white cisgender men designers. If looking for graphic design references, it will be easy to find out about modernist big shots like Swiss designers Joseph Müller-Brockmann and Armin Hoffman. Another thirty minutes of research could get you to women designers such as Rosemarie Tissi and Helene Haasbauer-Wallrath. Maybe you could then further explore how graphic design has been reworked since. What are the critiques of modernist design? How did designers from other cultural backgrounds and movements beyond Modernism approach visual expression?

Even though mood boarding is often considered to be a concise task, it’s crucial to expand your scope of research beyond the first few results shown on search engines. To create feminist paths, challenge the bias of the archives and platforms through which you collect images. This will also expand your own design knowledge and aesthetics.

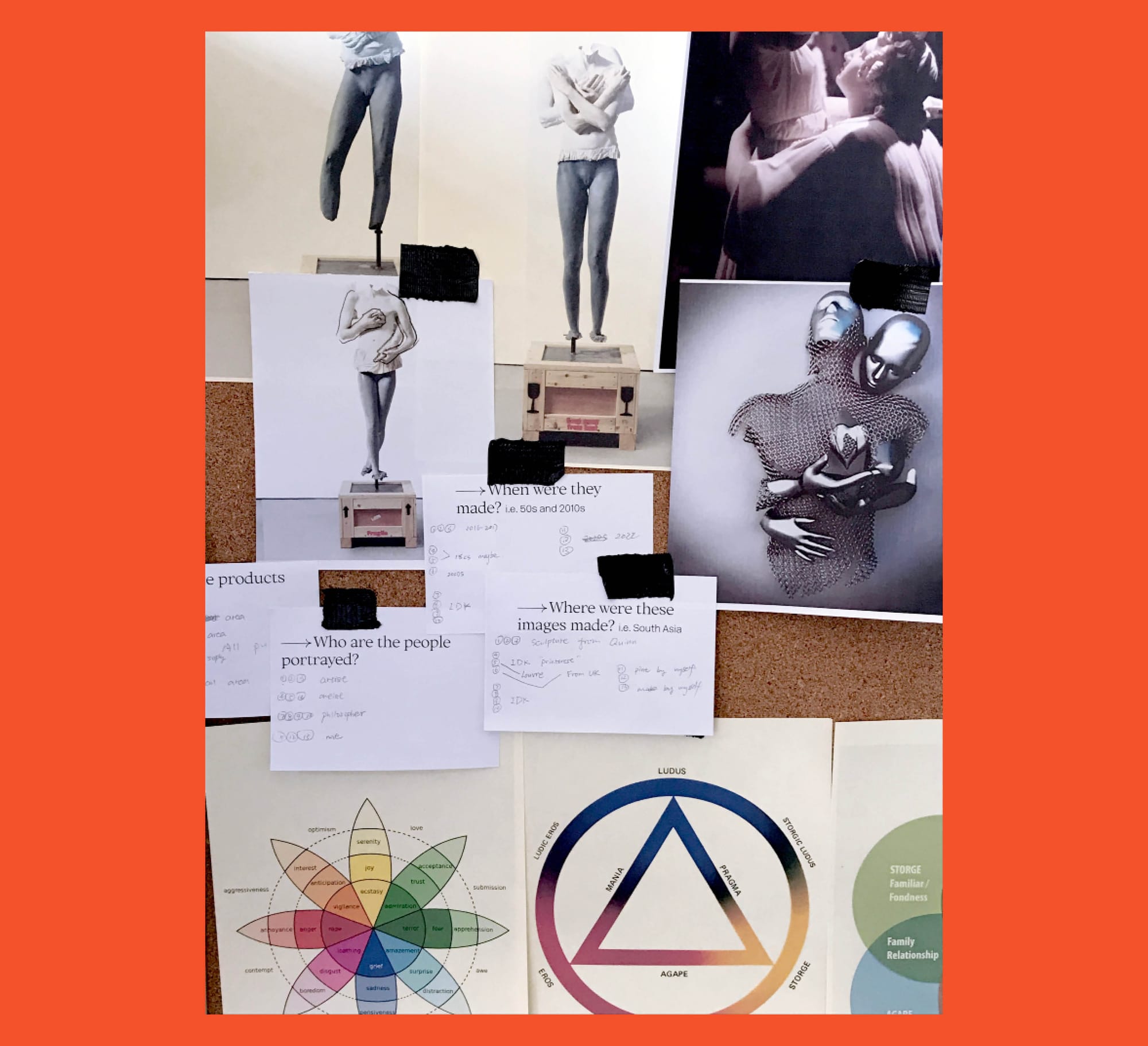

Analyzing: What is present and what is absent?

Midway through making your mood board, take a break for a visual analysis. This consists of examining the sources of your image collection, reflecting on what it includes and what it misses. Ask yourself:

- By whom were these images made?

- When were these images made?

- Where?

- In which context were they produced: commercial, artistic, institutional, or personal archives?

- What social demographics are represented (class, gender, sexuality, race, disability)?

- What are the main events and actions represented?

- What are the main emotions and atmospheres conveyed?

This exercise is an opportunity to recognize what is present and absent in the world you are building for your project. The midway analysis encourages reflection to approach the next steps of your research with more precision and purpose. For instance, you might have started a mood board on feminist art. This analysis could, perhaps, have you notice a focus on the visual languages of anger in feminist performance art. You also realize that your mood board contains a large majority of references from white cis-gender women and that most references are from the 1960s and 1970s. You can then continue looking specifically for works by women of color, trans women, and gender nonconforming people, as well as more contemporary works to explore their contrasts with the second wave of feminism.

Self-Reflecting: How does your positionality inform your choice of references?

The mood board also has the potential as self-reflective practice. Your image selection probably reflects what inspires you, your fascinations, and aspirations. Emotions and affect are key to the process of selecting images. As you collect images, reflect on how your positionality informs your choices and how your creative practice relates to this existing body of work. This will help you articulate more precisely what worlds you are bringing into conversations on your mood board and why. A practice that will also be beneficial is writing texts such as essays, personal statements, or project outlines. Alongside the midway visual analysis, this reflection can highlight limitations which, eventually, will inspire collaborations and further research.

Contextualizing: What future are you building?

The images on your mood board inform the creation of an upcoming product. Use the making of the mood board to explore scenarios of how this product will exist in the world. Respond to these questions by drawing and/or writing possible scenarios:

- Who is the end product user?

- In which context will the end product be used?

- Who is involved in the project and its production?

- Who is this project benefitting?

Use these scenarios to question the relationship of what you bring into conversation, and if it is relevant and appropriate in the context of your project.

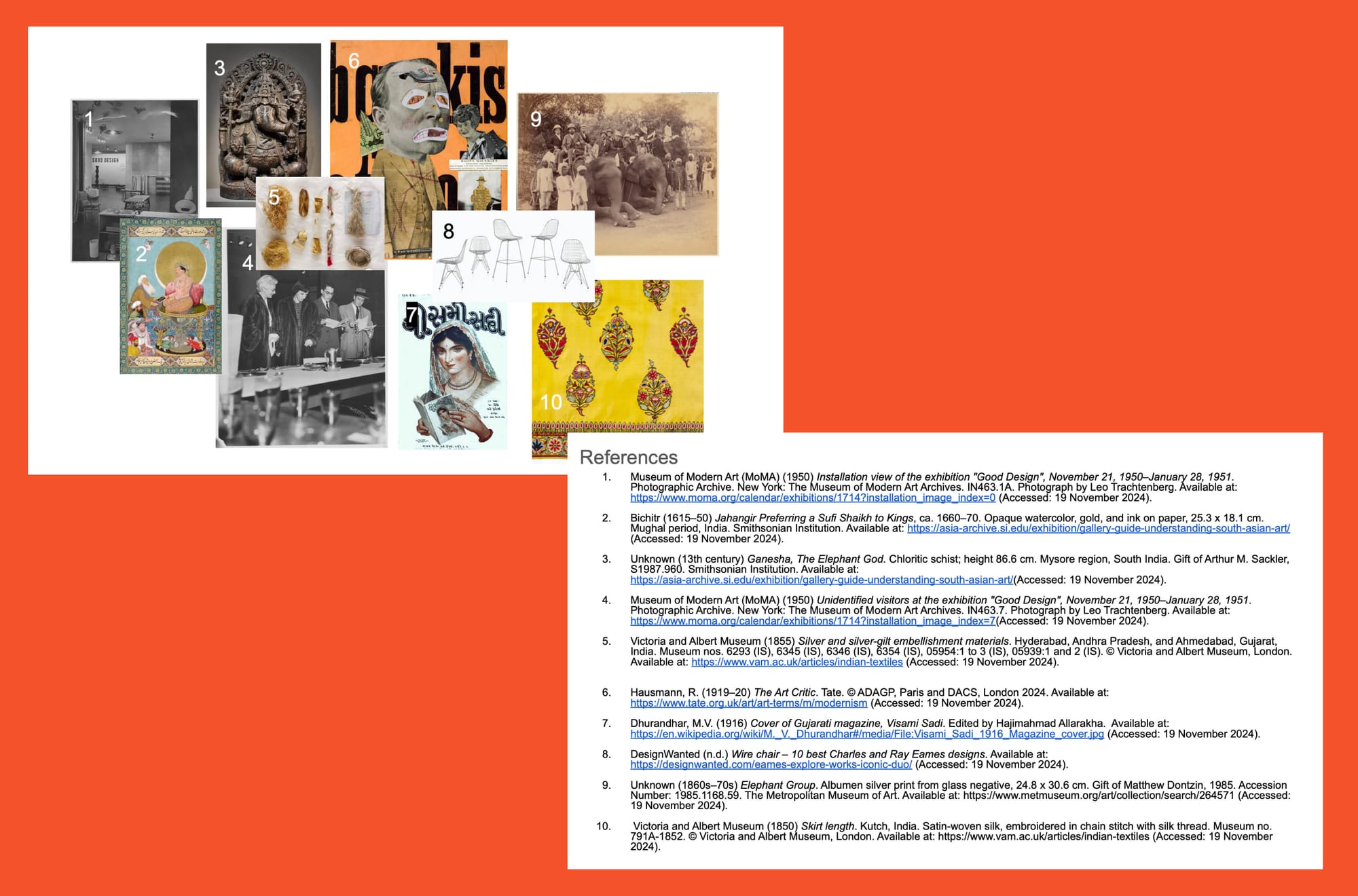

Including sources and credits

It is crucial to thoroughly keep track of all the sources of the materials included in your mood boards. This seems evident, but it is rarely expected when working with mood boards in educational settings and even less so in professional ones. In today’s digital culture, finding the original source of an image is increasingly hard. Credits are often lost as an image circulates across platforms. In this case, I encourage you to write “unknown source” to acknowledge that the source couldn’t be identified despite searching for it.

There is a lot of potential in reconsidering referencing systems for mood boards. Whereas essays use quotes and paraphrasing with standardized citation, the mood board compiles images from various authors but rarely uses a referencing system. And no, including credits does not prevent a pretty and moody board. Working with groups of students, I explored ways to credit and cite references that don’t “kill the mood” of their board, yet still clearly communicate the context of images. It is a matter of including your references in a user-friendly way, connecting each image to its source through captions, and possibly numbering while experimenting with typography and layout.

The juxtaposition of images in a mood board is a juxtaposition of histories. Researching and communicating about the context of images is a way to acknowledge the particular histories that come into conversation on your mood board. Including sources helps the users of the mood board (yourself, a colleague, or a client) to know about the stories of the images you brought together. It makes the process of re-contextualizing images both transparent and visible. The viewer of your mood board can then understand the variety of worlds you juxtapose to direct your creative process.

These suggestions might not be conventional practices in the industry. In a fast-paced professional environment, mood boards are briefly put together and are scarcely concerned with avoiding plagiarism or cultural appropriation. What I’m suggesting is definitely not a way to make your work easier. Rather, my propositions here demand more time and effort in making mood boards. It does take more work to find references beyond White men when researching design—and this isn’t limited to mood boards, but can be expanded also to sketchbooks, decks, treatments, and other visual documents. It takes effort to research the context in which each image was produced, and write down the sources in captions. They are not easier paths to take, but from our studios and classrooms we can—and should—develop more responsible citational practices.

Through the selection of which histories and perspectives we include in our references, we can challenge the reproduction of a design field centered on white men’s legacy and heteronormative, ableist, racist and colonialist oppressive systems. As Ahmed stresses in Living a Feminist Life, “You have to do more not to reproduce whiteness than not to intend to reproduce whiteness.” In this vein, our mood boards can carry out feminist memory through visual references and the care we put in the recontextualisation of feminist, anti-racist, queer, and crip legacies. Our mood board can be a practice with which we can nourish conversations with who we believe should contribute to envisioning our future, and insist on how we can build this future together.

Floriane Fo Misslin (they/them) is a researcher and design educator. They are a lecturer at London College of Communication and a doctoral researcher in Visual Sociology at Goldsmiths University of London in the UK, and a tutor at Design Academy Eindhoven in the Netherlands. Fo’s research examines how representations of gender nonconformity and queer sexualities are negotiated in processes of fashion production. Working with professionals and students in the creative industries, they develop participatory and visual research methods expanding the use of mood boards and diagrams.

Title image taken by Floriane Fo Misslin of Annabelle Willemsens’ mood board during a workshop at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts (KASK) in Ghent, Belgium, 2024.