You can’t know the full joy of serendipity unless you first seek it out. I discovered this recently, when digging in online archives led me not only on a journey far away into the depths of Swiss feminist history, but also back to my own neighborhood, and finally to conversations with four women behind a certain magazine.

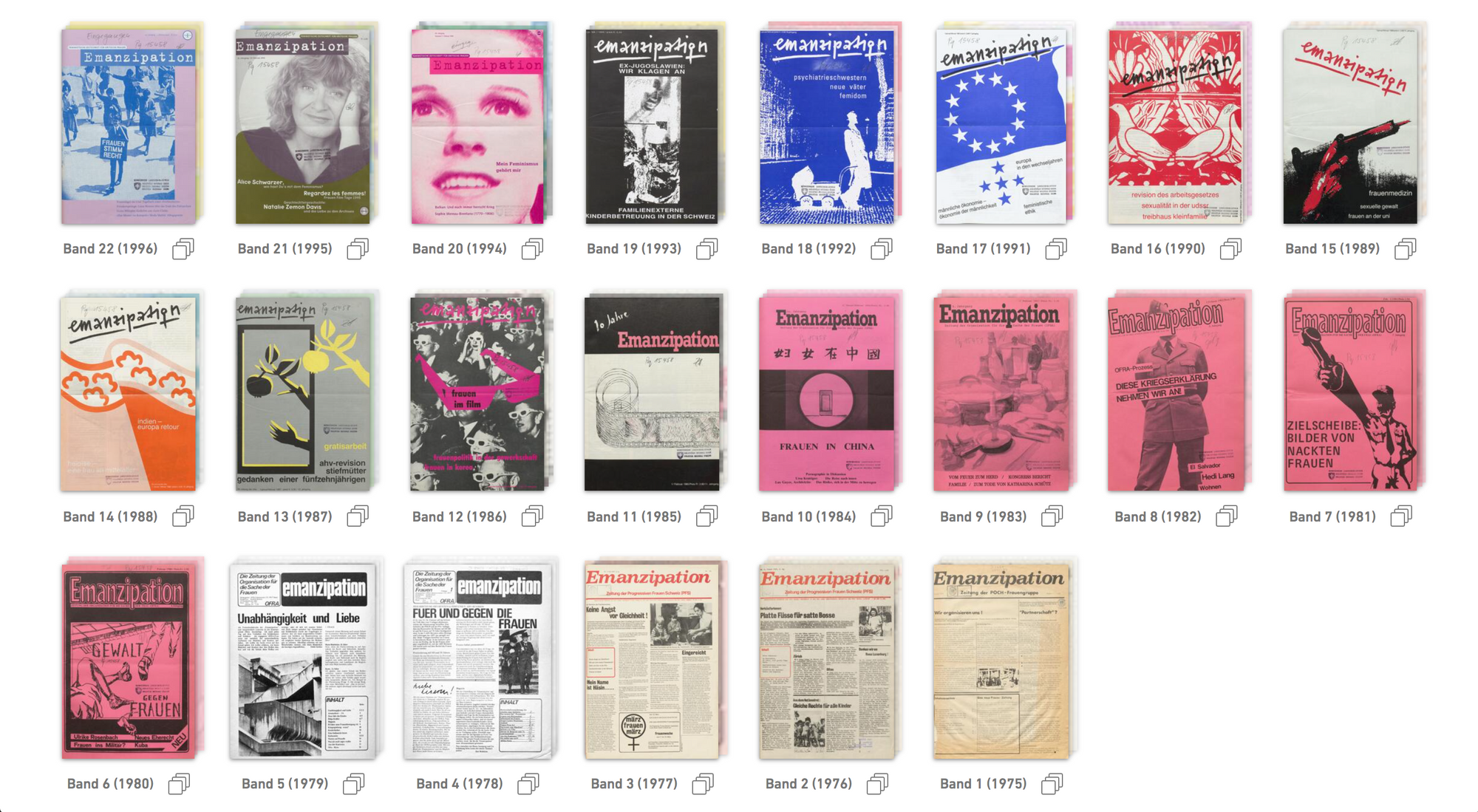

I first discovered the magazine Emanzipation (the German word for “emancipation”) on the web, while looking more generally for feminist periodicals online. This one was fully digitized. It was made in Basel between 1975 and 1996, where I live and study as a graphic designer at the moment. I tried to find information about the magazine, but I could only find a short text about it on the e-periodica.ch platform, where I found all the issues. The same platform informed me that Emanzipation was published by the Organisation for the Cause of Women (OFRA)—one of the most important organizations in the Swiss women’s liberation movement.

I started taking a closer look at the covers of the magazine, early examples of which are flooded by a distinctive pink, and I noticed how the design systems behind the covers changed three times over its twenty-year history. I read the Emanzipation’s imprints and editorials, which were filled with information and anecdotes about the work that went into the magazine. I found out that the OFRA was only created in 1977, and that the magazine was originally founded by a women’s group called the Progressive Organizations of Switzerland (POCH). Emanzipation became OFRA’s in-house magazine only in the year 1978. In the contributor lists, I also began to read the names of the various women involved over time.

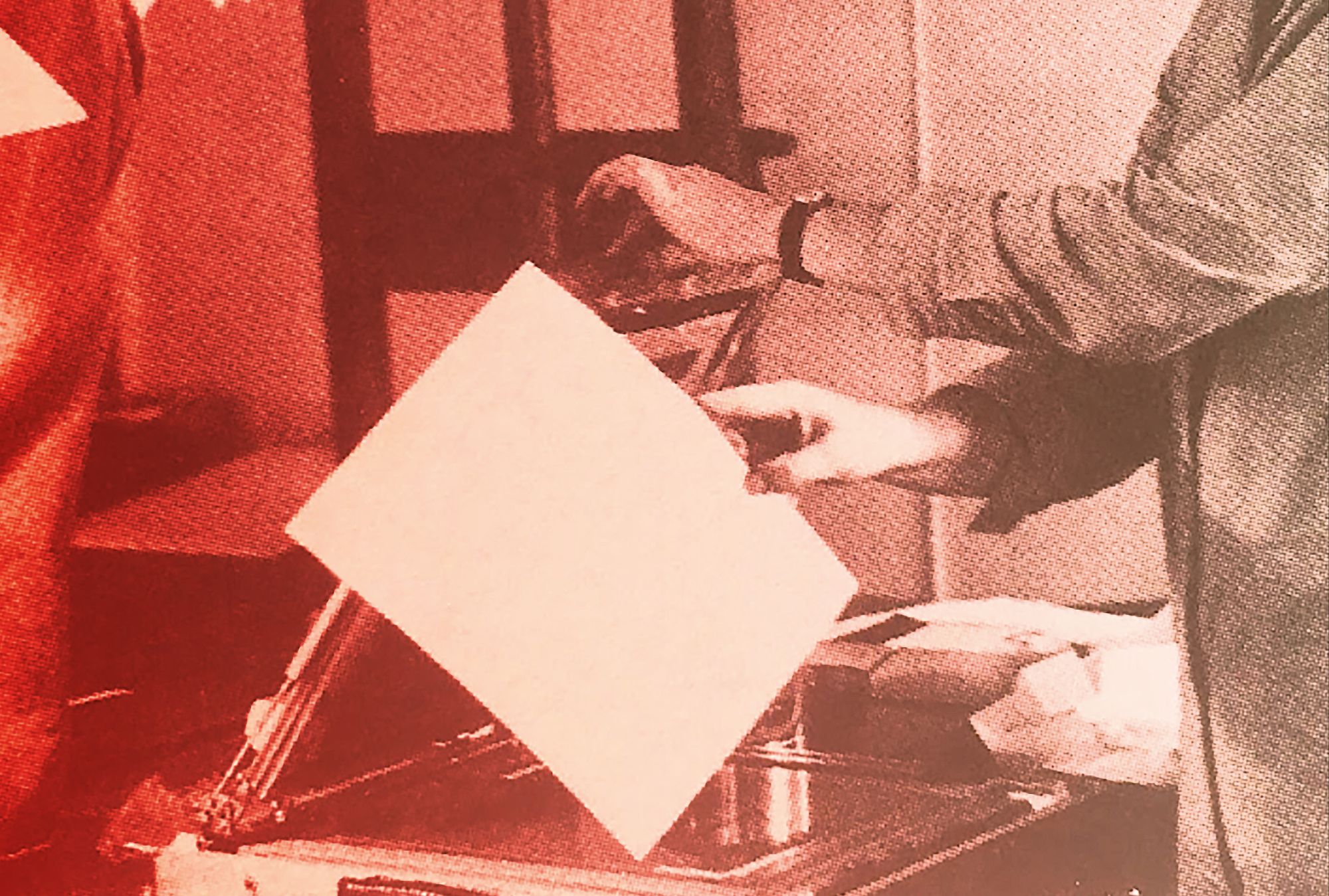

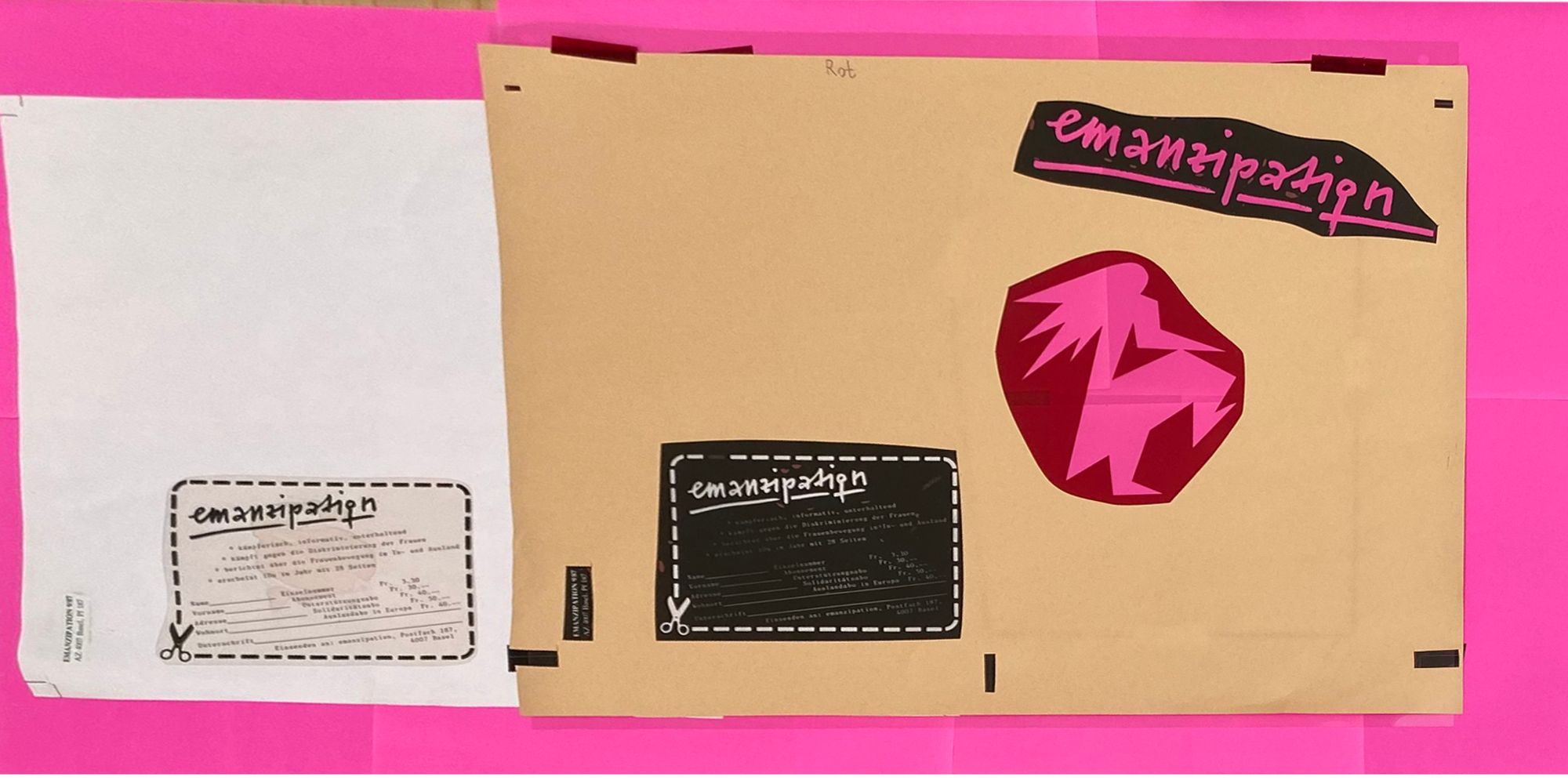

According to its editorials, Emanzipation was a collective endeavor, produced by volunteers. These volunteers also did the layout together until 1993, and from 1993 to 1996, the magazine had its own paid, external graphic designer. In 1980, a first change in the layout marked the editorial team’s aim to expand the magazine’s growth and sell it on newsstands: This is when the cover’s distinctive hot pink appeared—a strategy to grab a potential consumer’s eye. At this point, the team was publishing ten issues a year. I read on, learning about their annual team weekend, how they needed to raise the price of the magazine over time to keep going, about how they would have loved to make the magazine more professionally. Because of time restrictions and the voluntary basis of the work, the team’s possibilities were limited.

I started to imagine how it must have been back then. I thought about how I would love to talk to women who were part of Emanzipation. I wanted to sit with them and hear what it was like to create a magazine as a collective. Then during one spout of reading, I recognized a name on the contributor list. It was the name of a professor that many of my friends that study history in Basel work with. I contacted this professor, Caroline Arni, who then gave me the contact details of a “Caroline Bühler,” who had been part of Emanzipation’s editorial team.

The two Carolines studied together in Bern in the 90s, and it was Bühler who originally asked Arni to start writing for Emanzipation. While speaking with my mom, who’s of the same generation as the first contributors, she asked me whether the former National Counsellor and Councillor of States, Anita Fetz, couldn’t also have played a part? Turns out my mom was right: Fetz was part of the editorial team in the early years of Emanzipation and an active member of OFRA. I began to see how I might reach out to Fetz.

Before I connected with Fetz, another name had caught my eye on a contributor page, too: Anna Häberli Dysli. She was described as the specialist for the design in one editorial, which piqued my interest, especially as I was curious about the magazine’s collective design process. Thanks to a call for layout helpers in one issue, I came across an address for Dysli. I couldn’t believe it as I read the address. Can that really be?

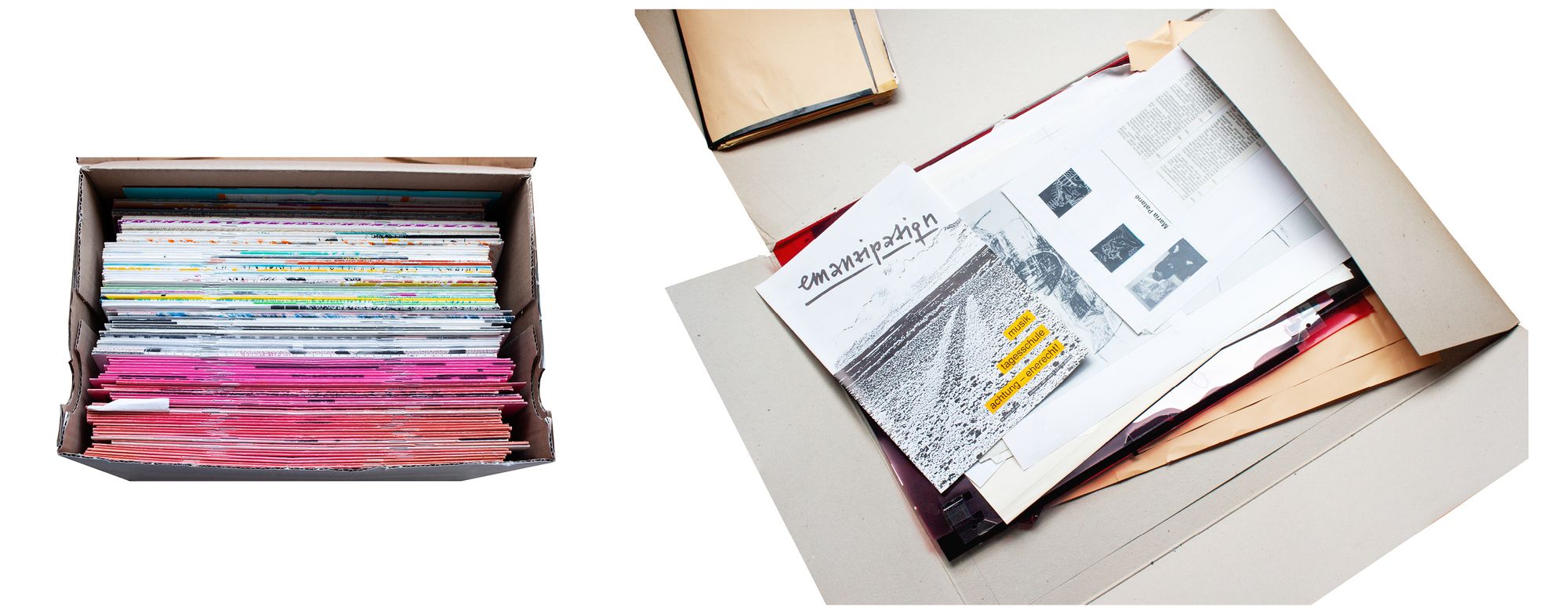

A look into the telephone book and a short, intriguing phone call later it was confirmed: Dysli still lives only one street away from me. A few days later, we met at her place and she told me that she had been taking courses at the Basel School of Design when she became part of the design team of Emanzipation. She told me about how the women created the layout for the magazine together in just one or two days, and how she would visit different women artists to ask them to publish their work. She told me about the feminist book club they had, and the annual OFRA party, which lasted two days—one day was only for women, and on the second day male partners were invited as well. At the end of our conversation, we both walked back to my apartment with a box full of issues that she entrusted me with, along with various originals from the layout room. An hour later, I was talking to Arni about her memories at Emanzipation. Then Fetz and Bühler over the next few days.

I now have in my possession an important personal archive, and around four hours of interview recordings. I’m sitting here, writing, and thinking about ways to share all of this and expand the research further. I took the time to pause, search, and discover. Now, I want to make this story accessible to others and contribute it to a history of Swiss graphic design, one sorely lacking in feminist threads and through-lines.

Noemi Parisi (she/her) is a Swiss-Italian designer and researcher based in Basel. In her current practice she explores topics of language, public space and discourse, archiving, and Swiss history from a feminist perspective.

This text was produced as part of the L.i.P. workshop, and has previously been published in the Feminist Findings zine.