Last year, during Australia’s stringent “lock-down” regime, a collective vision of the “public realm” was obscured. Viewed through windows, lens and screens, we were often greeted with stretches of emptied streets—with the occasional flashes of color and movement catching our eye. These flashes became amplified in the daily search for signs of activity outside our isolated bubbles. Color codes emerged that came to denote those select trades that were still permitted to move within a hastily redefined idea of “public” space.

In Melbourne, first there was the dark navy blue—somehow more metallic and sinister than ever before—that denoted the various forms of police, operating within an unfettered propagation of various departments and categories unified by this one color (the heavily armored “Riot Police” sent in to quell anti-lockdown protests being the most fear-inducing). Secondly, there was a vivid flash of Hi Vis emitted by the street and construction workers.

Not so long ago, both of these stubbornly hyper-masculine trades were identified by a synthesized ideal of the uniform that was utilitarian and almost universal. They both wore similar shades of blue (albeit in very different cuts and forms)—as did anyone donning serious workwear, such as your common, mass-produced overall or coverall.

This was eventually changed by the emerging proliferation of standards around workplace safety, which centered around the use of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) and high visibility-compliant garments. Initially, fluorescent, neon, Day-Glo and Hi Vis colours were sewn into straps and harnesses, then cut to form vests and tabards—until this color code completely replaced workwear’s previous swathes of blue. This change provided not only a neat visual separation between aforementioned trades, but also dramatically shifted perceptions around what a uniform or workwear could look like. While PPE’s origins lie in the realm of safety to avoid manual laborers and tradesmen getting injured, the developing trend also aimed to be fashionable in its own right.

Color-dyed Hi Vis garments provided a type of shorthand denoting a community of individuals who were certainly highly and confidently visible, but also afforded a type of invisibility when operating as a large group—as leveraged by Gilets jaunes protesters a few years ago (more about them later).

Stubborn trades & toxic masculinity

I mentioned earlier “stubbornly hyper-masculine trades.” Recent news events in Australia report some shockingly misogynistic behaviour taking place within Parliament House. These include the use of (formerly) safe spaces for hosting sex workers, the committing of lewid acts in workspaces, and rape within ministerial offices. In some fields, within Australian society, parity between binary genders has been achieved or surpassed, paving the way for the inclusion of definitions beyond established binaries. But in other places—as exemplified by these recent events—“parity” and “visibility” have started running in reverse, creating easily recognizable enclaves within the echelons of colonially constructed society.

In 1986, the Australian Government created the Workplace Gender Equality Agency in recognition of their (continuing) failure to address issues of inequality within many leading industries. It is no coincidence that their homepage features an image of a woman in Hi Vis on a construction site. In 2020, it was reported that the “Construction” sector had the second highest industry gender pay gap, and the second lowest percentage of women in their workforce (18.1% women to 81.9% men). Even within healthcare—an industry with the most visibility for non-men—they noted that the gender pay gap has barely shifted in three years, and that there was also little improvement in the representation of women on boards.

Mental health issues within some of these male-dominant industries is another cause for concern. The consolidating of hegemonic, toxic or hyper-masculine culture within certain trades—and therefore workplaces—has proven to be detrimental to workers, in particular within areas of the construction industry, and not just in Australia. This industry is known to have the highest number of suicides—notably, mostly by men—by profession throughout England. Britain’s biggest construction project since World War II is a nuclear power station near Bristol called Hinkley Point, which started in 2016 and is still under construction today. In 2019, a news report on Hinkley Point revealed a steeply climbing rate of absentees due to stress, anxiety, depression and suicide.

“Malcolm Davies, a civil convener for the U.K.’s main construction union, Unite, made a direct link between spaces identified as being “hyper-masculine” and the mental health of the men that inhabit these sites”

Reasons for this ranged from the isolated nature of the site—workers were away from family and the general public for prolonged periods—to the precarious nature of work contracts and terms that lead to job insecurity, bullying and peer pressure (sometimes compounded by drunkenness and gambling), and a lack of structure in reporting these issues. Many of these are tied statistically to overwhelmingly “male” environments. In a 2019 article, Malcolm Davies, a civil convener for the U.K.’s main construction union, Unite, made a direct link between spaces identified as being “hyper-masculine” and the mental health of the men that inhabit these sites, stating: “Construction is a very macho industry. [...] [I]f you’re the big bloke and you say you can’t cope or you are seen crying, you get ridiculed.” Since this report, many actions were taken to address these issues on the site and within the wider industry, but the image lingers of groups of men made anonymous by the Hi Vis garb they wear—the vibrance of the garments concealing a myriad of potentially dark thoughts and unhealthy behaviours.

Together alone

Part of Melbourne’s stringent lock-down regime included a 5km radius from your point of origin, within which you could walk—for around one or two hours—to buy necessities or to exercise. We realised most of the Central Business District was within our 5km zone, and bravely ventured into the center of the city. A smattering of fast-food outlets, food stores and supermarkets were open. There was a queue of students encircling a city block, each waiting patiently to collect a box of provisions from a city church that had taken up the slack after the state and federal governments refused to help support the vast international student population that was now stranded. Many shop fronts were papered over or left empty. Some had mannequins stacked up, undressed and leaning against shop window glasses. Billboards and screens were turned off or left empty. Public transport kept running in support of a mostly invisible fleet of “frontline workers,” although patronage was sparse. A largely empty tram rattled past with an ad for the local construction union on it, stark against the exodus of advertising and merchandising displays.

In this ad a group of seven, largely identical-looking men in Hi Vis stand atop a skyscraper, with the city—as a cold, dead, grey landscape—spread out behind them. Their arms are raised, with fists clenched in solidarity, as if having won a victory, reflecting the type of propagandistic World War-era graphic iconography often fetishized today. Text floating above them decrees: “Together we will lead the recovery of this nation.” “Together” appeared to denote the group in the ad, rather than any wider vision of a collective society—or maybe this was a new vision of a society, whereby any folks who didn’t identify with this hyper-masculine cohort were rendered colorless or invisible.

Without a diverse collective audience, Construction, Forestry, Mining and Energy Union (CFMEU)—notably, all categories often under scrutiny for their wantonly destructive behaviour, particularly towards land rights and Australian aboriginal people—was one of the few organizations happy to spend funds on a new outdoor advertising campaign. Possibly, they assumed it would be their members who would be most likely to see it (Hi Vis to Hi Vis).

In this case, Hi Vis now highlighted those with the privilege of continuing to earn a wage, and continue on as if nothing had changed. Indeed, construction seemed to go into overdrive during Melbourne’s lock-down, with the Victorian branch of the CFMEU arguing a case for defining construction workers as “frontline workers” and allowing sites to open 24/7—despite the disruption and effect on the mental health of those in the immediate environs—confined to their living spaces, with many facing uncertainty regarding their own ability to maintain an income.

While, of course, no industry should be devalued for fighting to protect the livelihood of their members, in this instance there were stark lines of privilege and visibility afforded to these hyper-masculine trades above others.

Diversity washing

Construction industry unions often seem to perpetuate a hyper-masculine, on-top-of-the-world, natural-leaders-of-a-(male)-realm—despite utilizing Hi Vis campaigns to encourage and celebrate diversity. In talks about gendered violence, the union defends: “Doesn’t matter if you’re male or female, black, white, green, gay, straight—whatever. That’s what we do. We look after workers.” However, it is evident that these groups are politically intertwined. The union harbours an extensive merchandising operation which, in turn, clothes members in various aspects of the union’s aims and imagined appeal. Their public-facing campaigns are largely exercises in “diversity washing,” with messages embedded into their merchandise that vary wildly in tone. These range from Union Pride t-shirts paraded at gay pride marches alongside images of “Rosie the Riveter” and “Unity in Strength. Solidary” t-shirts incorporating Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander flags, to the sort of purposefully inflammatory statements Union “boss” John Setka happily flaunts such as “Battles Solve Everything” and “If provoked, Will Strike” (alongside hyper-masculine symbols such as skulls and cobra snakes), to curiously blasphemous slogans such as “God Forgives, CFMEU doesn’t.”

“As much as the wearing of fluorescent yellow tabards acts to identify industries and groups, it also allows for a smudging of identity between groups and individuals.”

Gilets jaunes

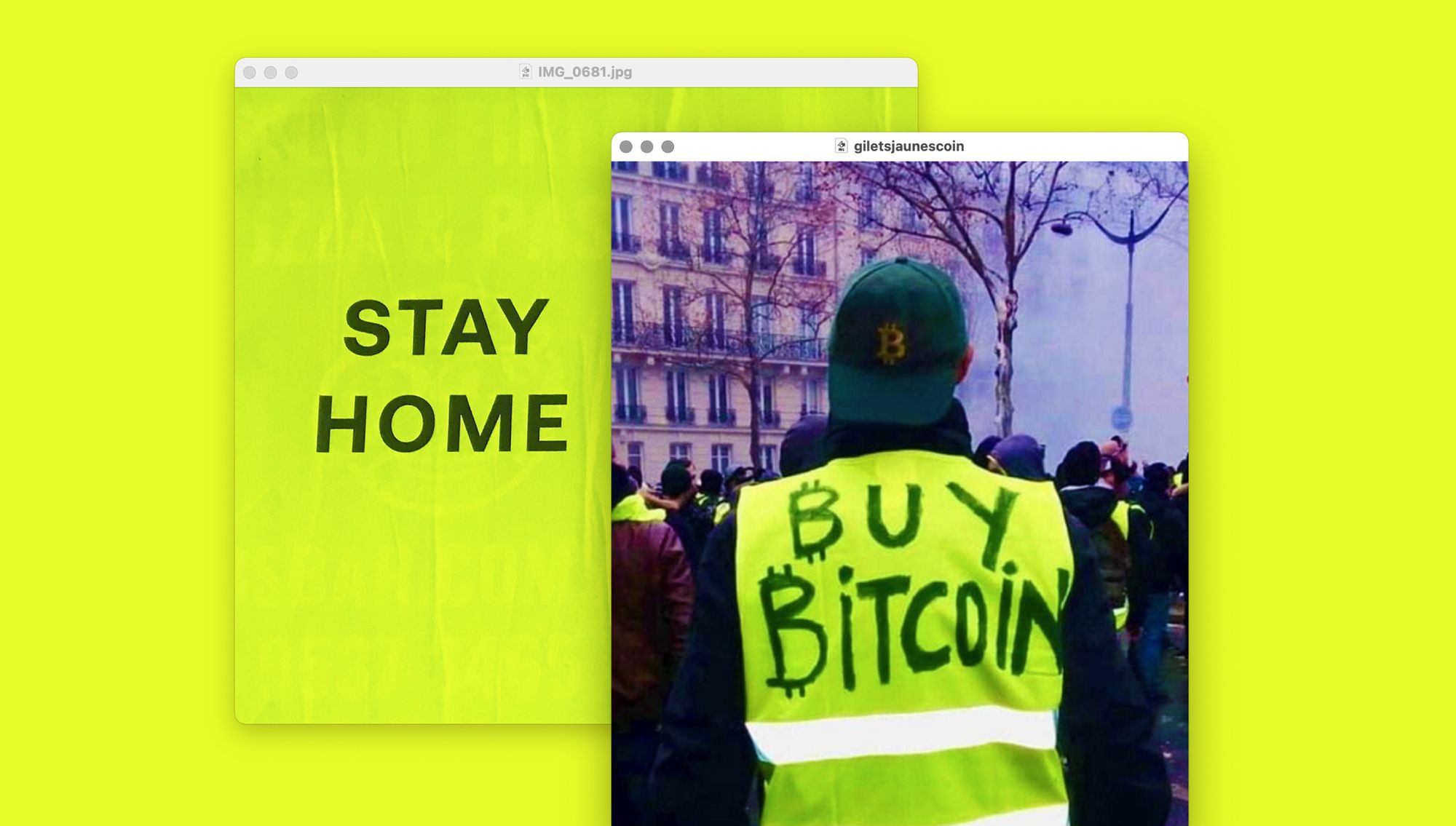

The flickering between personal and political life that Hi Vis affords is something the Gilets jaunes protesters exploited during a season of protests that erupted in 2018. These isolated pockets of protesters spread from their initial source, spilling across physical borders and ideological boundaries.

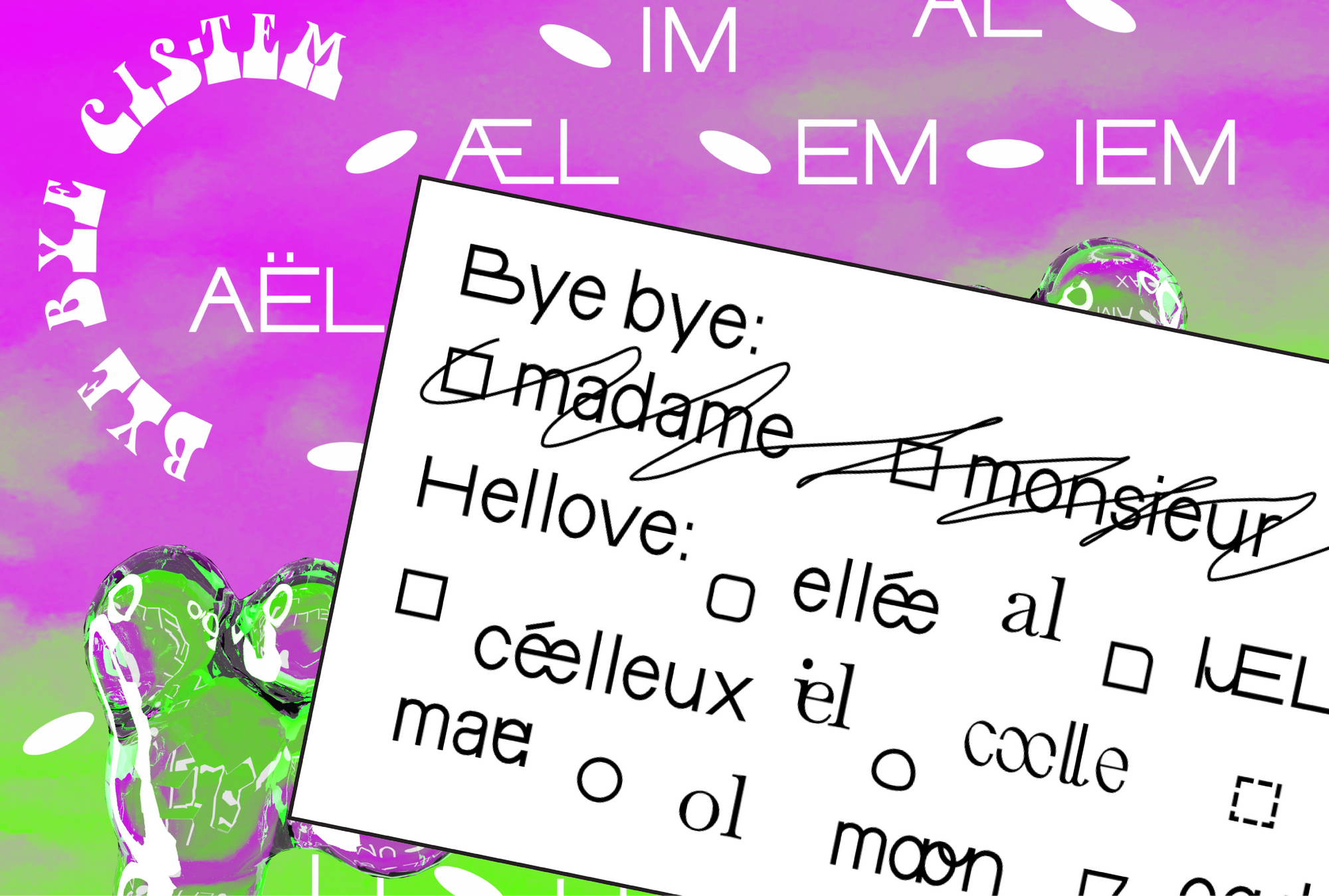

As much as the wearing of fluorescent yellow tabards acts to identify industries and groups, it also allows for a smudging of identity between groups and individuals. Initial Gilets jaunes protests were instigated by French (predominantly middle-class) citizens protesting tax rises on fuel—combined with an edict that decreed that drivers in France should carry at least one Hi Vis vest with them, in their cars, at all times. The ease of access to this vibrant symbology enabled other protesters to easily join in unison. Protests then spread swiftly around the country before jumping borders and channels into places outside of France, where the initial message was dispersed further, inviting an array of diverging concerns.

When Gilets jaunes protests moved across the channel to London, they were initially worn by pro-Brexiteers picketing Parliament House to push politicians to hurry up the process of leaving the EU. Pro-EU protesters started wearing them to counterbalance initial protests. Soon, anyone with access to a marker and a vest were making demands or fatuous statements in protest at all manner of things, such as the installation of 5G networks, or to urge others to buy bitcoin—not to mention its use in a new cryptocurrency named the giletjaunecoin (I kid you not).

Hi Vis as social consciousness

As much as Hi Vis has been used to voice antagonism via protest, it has also been deployed in the monitoring of the “right to free protest” by Legal Observers. In Victoria, Australia, Legal Observers have increased their presence in reaction to continuing legislation and policing behaviour aimed at quelling the right to protest. In doing so, they have separated themselves from Legal Observers in other places by choosing fluorescent pink. This has made the volunteers attending events less anonymous, but also easy targets.

For example, state-sanctioned police targeted a select group of housing commission towers, in order to enforce a stringent lock-down measure that included handing residents detention notices, without explaining how they would access supplies. Many of us looked on in sympathy and horror at their treatment through our screens, often viewed over the shoulder of a pink-vested Legal Observer, who risked illness and arrest to provide a watchful (recorded) eye over events to ensure the tower residents had a voice within the proceedings.

Their avid, and very welcome, monitoring of colonial policing strategies has been so effective and continuous that, since lock-down—when police and those donning Hi Vis were often the only ones visible in public—they found themselves the target of the sort of police behaviour they set out to monitor.

“Chainsaws tearing through (our) heart(s)”

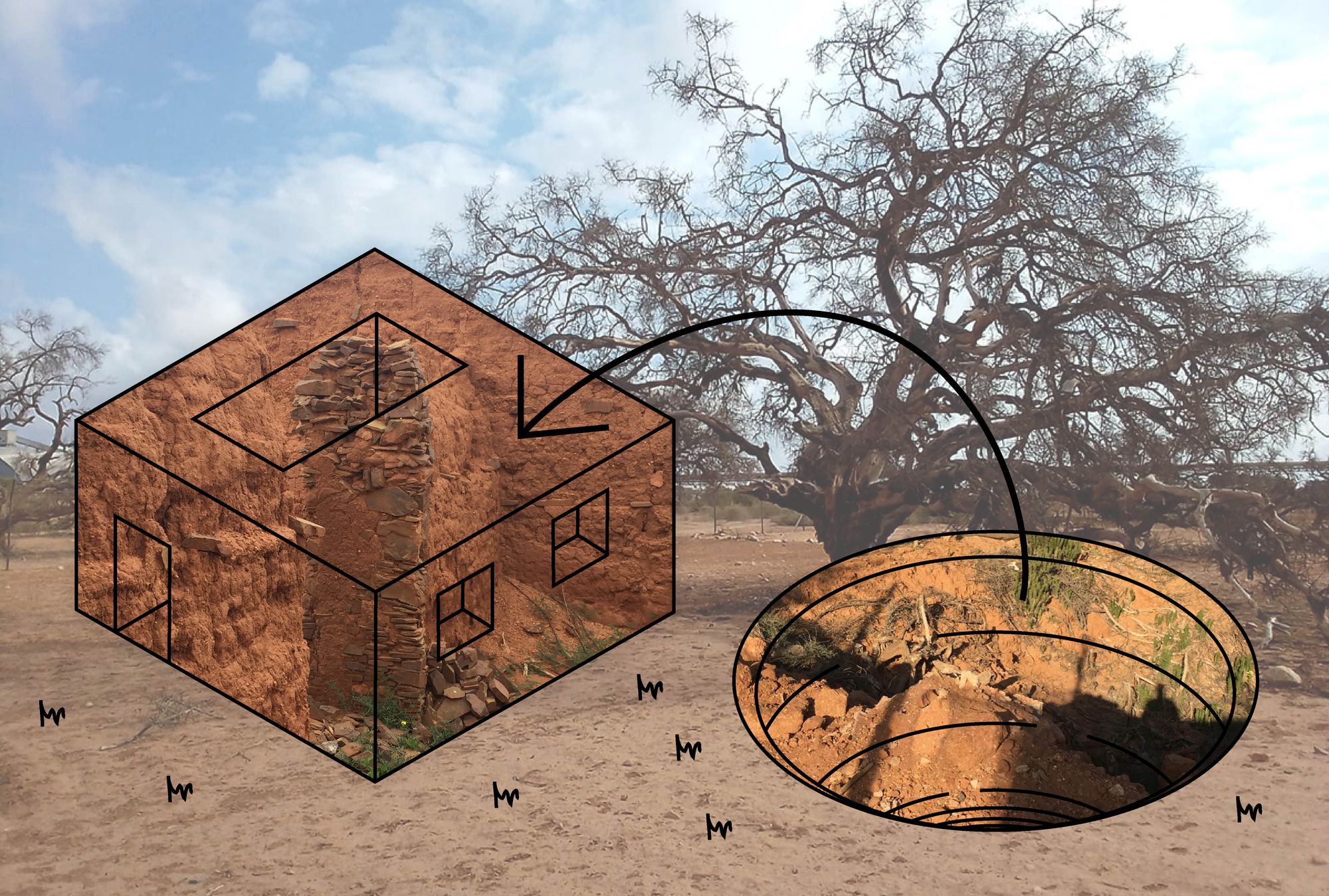

In one particularly distressing case, the local roads authority, VicRoads, took advantage of the relative invisibility “lock-down” afforded road construction workers to accelerate already highly destructive practices around the removal of ancient trees for highway widening and fire-clearing projects. A grove of around 3000 trees near a place called Ararat outside of Melbourne, Australia, had been earmarked by colonial authorities to be cleared. These were ancient trees of particular significance to local Aboriginal groups, including 800-year-old and 350-year-old trees believed to be sacred.

After continuous monitoring throughout lock-down, Nerita Waight, co-chair of National Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Legal Service, and CEO of Victorian Aboriginal Legal Service, released a statement indicating that police had blocked road access to the sacred Djap Wurrung trees, refusing access for lawyers as they were “non-essential workers.” The statement also noted the racial discrimination of policing, noting that at least 50 activists were arrested and fined.

As with any police action surrounding protest, Legal Observers were on site to monitor police behaviour, only this time—away from journalists, formal legal associates and a “general” public—the police in attendance saw the non-familiar flash of fluorescent pink that has proved significant in holding them to account for recent discriminative actions, and responded with arrests—and in some cases, with extensive violence despite the victims’ willingness to comply. As one legal observer noted: “I agreed to move on. They arrested me immediately despite my compliance. They walked me out, away from my position as a legal observer, holding both of my arms. I was wearing the clearly marked legal observer vest throughout the whole ordeal.”

An expanded vision of social acuity

Researching Hi Vis as a social phenomenon unravelled threads that lead to many urgent issues. Yet, the intent for which it is utilized and deployed often shifts dramatically. It is clear that Hi Vis has become a potent signifier, but also one with momentary allegiances. Hi Vis is a volatile substance. Impossible to ignore—even though it is often unclear. The more you search for specific meanings, triggers or connective tissue, the further dispersed this field becomes.

In the instances mentioned here, use of Hi Vis shifted from highlighting the pooling of mental health issues within toxic, hyper-masculine trades; to lack of income equality during Covid lock-downs; to diversity washing within the trade union movement; to its use in uniting divergent communities of protest via its use by Legal Observers as (previously) passive resistance to colonial systems of policing. These were only a few examples selected from a much wider research pool.

Hi Vis demands attention beyond the scope of a singular investigation, but maybe what this activity really pointed to was a type of “social acuity” design research (defined here as research undertaken by designers) not only affords, but in which it can excel. “Social Acuity” is just a starting point.

Savior Mode activated

Many encouraging conversations have arisen in very recent times around the role of design in societal terms, with both positive and negative impacts. At many times, this has encouraged designers to participate in a type of “savior mode”. The idea is that if the fine-tuned acuity of the designer to color, to form, to type, and to design is turned towards the many issues stemming from the human-designed world, then maybe we start fixing things—to redesign the world.

“‘Solutionism’ becomes a lofty goal assigned to designers that requires the type of future vision that working designers understand, but on which they may not necessarily have the capacity to work.”

This is a trap. For many, the acuity to see and clearly define a problem can be a long way from being able to “fix” said problem, with the tools and abilities with which designers associate. Fixing one issue can also generate a host of new issues, or defer a set of issues until a later date. Design’s “Savior mode” is a good look, and it’s been seen as “good for business,” but it also acts as a balm to designers’ insecurities relating to our role as producers, in a world weary under the weight of the evolution of industrial and cultural production. “Solutionism” becomes a lofty goal assigned to designers that requires the type of future vision that working designers understand, but on which they may not necessarily have the capacity to work.

In these cases, maybe it is our particular acuity that can be put to better use. There are already many examples of designers shifting their acuity from purely aesthetic concerns to wider, societal issues with the benefit of expanding their participation within many other diverse industries and fields. Designers are often in the position of intermediaries, incidentally giving us the perfect vantage point from which to practise “social acuity”—to highlight work that needs to be done, even if we are unable to do the work ourselves. When you start to follow the many threads that Hi Vis and the designed objects that use it weave together, this acuity becomes clear.

Michael Bojkowski (he/him) is a designer, writer and sessional lecturer at RMIT University in Melbourne, Australia. He is also a recent graduate of the Critical Inquiry Lab MA at Design Academy Eindhoven.

The Hi Vis Index is an emerging project seeking to document instances of the designed use of fluorescence and instances of social acuity connected to them through an “index” of case studies. If you’d like to contribute writing or research, please contact Michael via @research.catalogue or rescat.site

This text was produced as part of the Troublemakers Class of 2020 workshop.