Sandra Benites is an anthropologist, educator, and cultural advocate from the Guarani Nhandewa people of Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil. With a profound connection to her roots, Sandra works to amplify Indigenous voices, particularly those of women, in spaces often dominated by non-Indigenous narratives. Her work challenges the invisibility of women’s experiences and highlights the importance of including their perspectives in decision-making, storytelling, and education.

In the following text, originally published in Portuguese by the Brazilian magazine Piseagrama in 2020, Sandra Benites writes as a kunhã py’'a guasu—a woman with a feeling of courage. In her writing, Sandra introduces the concept of teko—a way of being and seeing the world that is dynamic, relational, and deeply tied to Guarani cosmology. Drawing on her grandmother’s teachings, she recounts how Guarani women navigate the challenges of preserving their traditions while engaging with the juruá (non-Indigenous) world, often in spaces that fail to recognize their needs, rhythms, and histories.

In her work, Sandra calls for an education and a world that would honor Indigenous knowledge systems, resisting the homogenization and silencing imposed by colonial structures. She shares her journey of becoming a bridge between worlds, speaking of the significance of collective care, and the importance of respecting diverse ways of being. Through her words, she reflects on the essential role of women's wisdom, care, and courage, positioning the female body as a site of knowledge, territory, and resistance.

Women cannot stay silent. If, among the Guarani people, stories are told mostly from a male perspective; I write to include women as protagonists in their decisions and demands. How can one move between the Guarani world and the non-Indigenous world without getting lost in both?

In our oral tradition, each narrative has to be told from the individual perspective of each teko. Teko is a way of being; a form of being in the world and of seeing it. The teko is created and transformed during one’s path. It is a process, always in movement, and its transformation is due to the life experiences of each of us, as well as our relationship with what is around us. There are women’s teko, and there are also teko specific to mothers, men, children, young people, older men, older women, women who have relationships with women, men who have relationships with men—these ways of seeing and being in the world are all different.

We, Guarani people, are always searching for teko porã, the well-being of all teko. If each teko does not have its own voice, they can be erased; they can suffer homogenization, as if they were all the same, or as if some were more important than others. The teko depends on the moment, and on who is speaking. There are two versions of the Guarani oral narrative: the men’s and the women’s. However, the women’s version has been disappearing; the men’s hasn’t. That happens because the men usually have more contact with non-Indigenous people, so they can narrate their ways of being.

In most cases, we only hear about the life of Guaranis through a generalized male perspective. Women end up invisible, their importance to society obscured. I write to include them as protagonists in their decisions and demands. I tell my story so that other women can recognize themselves in my journey—so that the executive, judicial and legislative authorities, as well as universities and researchers from different areas, recognize the importance of our protagonism.

I was born and raised in the village of Porto Lindo, in the state of Mato Grosso do Sul, where I started my school life. My extended family comes from the Porto Lindo tekoha, where they still live. In the Guarani language, tekoha means our territorial space. My aunts always wanted me to be a leader in caring for children and women’s health in the community. I stayed with my djaryi, as we call our grandmothers, in order to study while my parents worked on the farms.

My djaryi was fundamental for my reko—my consolidation, my being a woman, a mother, a student, and, today, my being a researcher. She went out of her way to show me that there are differences in body care practices between girls and boys. She also knew how to differentiate the specific moments of each stage of life, understanding how to deal with the structuring of the body over time: for boys, she emphasized the deepening of the voice; for girls, the first menstrual cycle. She spoke of kunhangue arandu, the wisdom of women; kunhangue reko, the women’s way of life; and kunhangue resãi rã, the good future of women’s health. As she was a midwife, she always paid more attention to the girls, guiding us on how to take care of our bodies.

At that time, my story began: I built myself as a kunhã py’a guasu—a woman with a feeling of courage—while accompanying my grandmother in her tasks. I went with her to the women’s homes every time she was called to deliver a child. And, during those journeys, she would tell me sad stories about her desires and her real difficulties. She told me, for example, about the difficulty of understanding what the group of missionaries told my grandfather when they arrived in the village. She only spoke Guarani language; she didn’t speak any Portuguese.

“The experiences lived individually are reflected in the collective; they are thrown into the collective, regardless of whether they are good or bad.”

In Guarani society, the body and tongue are the basis of wisdom. The construction of physical and symbolic bodies take place according to needs and environments, always considering cosmology and customs. The experiences lived individually are reflected in the collective; they are thrown into the collective, regardless of whether they are good or bad. I speak from the perspective of a Guarani Nhandewa woman. I talk as a sy—mother, and a djaryi—grandmother, when I narrate my grandmother's teachings.

We build ourselves as women from the first menstrual cycle and learn to take care of our bodies. During menstruation, we stay safe at home, avoid certain foods, stress, or excessive noise, and keep the body warm. We build our territory in our own way. I say “territory” because the functioning of our bodies and our way of being women are territories and identities; they relate to differences and specificities women face. Social rules are different for women, in order to meet their demands. From our identities, bodies, and needs, we can build our rights, as well as public policies for all women. That’s what I call “territory.” I realize that this discussion allowed me to better understand the term teko, our way of being. The tekoha is where this way of being is developed.

Each body is a territory. We always try to respect each other’s teko, even if we are not the same, in order to balance the flows and movements of the place in which we find ourselves. The place in which we move is moved by the people in it. If people are not in harmony with each other, the site will not be well either. For the Guarani, the tape porã, or good path, is always also related to others. For women, however, it is often difficult to reconcile their bodies with the environment in which they are. Therefore, I believe that the wisdom of the Guarani women must be told by the women themselves. The mythical story of Nhandesy is accountable for how the nhandereko, the Guarani way of life, is organized.

Arandu is the knowledge passed on through oral narratives, always mentioned in the story of Nhanderu Ete and Nhandesy Ete. My grandmother explained that these stories must be told to the next generation of boys and girls, so we don’t make the same mistake as Nhanderu Ete and Nhandesy Ete. Nhanderu created the Guarani woman, Nhandesy, and was supposed to create a man to live with her on Earth and populate the world. However, that was not what happened. Not resisting the charms of the woman he had created, Nhanderu himself became a man and came to live with her on Earth, even though he knew he couldn’t stay.

My grandmother used to say that Nhanderu is a spirit similar to air; he has no body and no fixed place, so we can’t see him or touch him—we just feel him. The woman is from the earth; she has a substantial body. Nhanderu then had to return to the divine place. Nhandesy, not understanding what had happened, started the Hete Omonhono—the path in search of her husband. Not being able to find Nhanderu, Nhandesy was very sad and frustrated, and overcome by grief, she got lost. That’s why my grandmother used to say that a real man is one who always tells the truth to his wife. Boys and men who disrespect a woman attack and deceive their own bodies.

“Women cannot take on all the responsibilities alone. Most of the time, there are excessive demands placed on women.”

Women need, first of all, to take care of themselves, as they are the “joy of the house,” as my uncles used to say. If the people around them are not patient, they will become angry, lost women, as happened to Nhandesy Ete because of Nhanderu. Those feelings can also infect the people around them. Women cannot take on all the responsibilities alone. Most of the time, there are excessive demands placed on women, and then they in turn have to put pressure on their children, their husbands, and their brothers. That is why a woman cannot be afraid or ashamed: if we do not teach our children, our brothers, and our husbands, there is a risk of joawy—imbalance. My grandmother used to say that if a woman becomes overwhelmed, she gets py’a tarowa—a feeling of dread—and she will take it out on the people around her.

In the Guarani culture, in general, the wellbeing of each one depends on the other. In order to avoid joawy, the imbalance, the communities must be joorãmi meme—equal. Guarani Arandu is the knowledge that teaches the importance of caring for the other. Taking good care of others means taking care of oneself. In a community, the action of an individual always reflects on others involuntarily. Each person’s actions are launched towards the collective so that the rhythm is that of the community. The suffering of someone is always linked to somebody else. Sometimes, for example, moving to another village can become necessary in order to avoid causing others suffering and pain. That’s why it is important to listen to everyone: if one fails, everyone suffers. There is no way to think about anything in individual terms. This practice occurs through listening.

When I heard the story of Nhandesy as told from the perspectives of men, I felt compelled to talk about our knowledge. The Nhandesy narrative holds power; it cannot be told only by men, because that would mean a kind of domination over women. The story is different when told from the perspective of women. The same thing happens in schools and universities.

When I went to the city, it was challenging to adjust. I had to understand the juruá reko—the behavior of non-Indigenous people—as well as my own boundaries in dealing with that other teko. That does not mean I became juruá, but I learned how far I can go. I can give up some things, but I cannot forget myself and act like the juruá women, running from one place to another, hiding their bodies, and acting like men—like they don’t exist in their own space.

The production of the body and of things is a complex process that requires several duties, distributed through the different stages of life. Each woman’s process is always based on the context in which she finds herself: whether she is pregnant, menstruating, studying, or working. Each moment of experience requires a type of arandu—knowledge. Our relationship with the land and territory and its resources is significant to maintain the arandu, including that of women.

The places that women occupy in juruá institutions and the places where they circulate in juruá society are not designed for the bodies of women. There is no concern among them to meet the demands of a specific body. Their systems are designed for men. Theirs are places designed for the body of men, as if all bodies were men’s bodies.

By occupying spaces outside the village, my py’apy—my apprehension—increased. I felt great uncertainty living among the juruá, who speak little or nothing about female issues such as menstruation, body care, and the protection of women. Juruá women do not do resguardos—ritual acts of protection, often involving isolation or dietary restrictions—like us Guarani women. How can we practice the relationship between the micro, individual teko, and the macro, collective teko in the tekoha of the juruá, in which the universe is so strong that it overlaps the women’s arandu? How to keep our microcosms, even away from our family groups; even without drinking chimarrão—an infused yerba mate drink—without cooking our own food around a campfire, without listening to life stories?

“Our body is our place of knowledge. Each body has its own reko—its own demands.”

It is outside the village, when working and studying, that the Guarani woman finds kuimba’e kuera pu’aka—“male domination”—since her arandu is neither recognized nor respected in a society that seems to be made for men. Women have always needed to take care of their children, the family routine, and themselves, and nowadays they need to work and study like non-Indigenous women. Thus, we, Guarani women, present ourselves in other spaces, adopting another image and adapting to it. This leads to violence against the Guarani female, who menstruates, becomes pregnant, gives birth, who is a mother, and who speaks as a woman.

Our body is our place of knowledge. Each body has its own reko—its own demands. Each moment in time has its own symbology and its spatial needs, whether we are referring to kunhã (women), kuimba’e (men), mitã (children), or kyringue and tudjakue (elderly men and women). People around should respect and contribute while women are building healthy bodies. The process of producing healthy bodies does not depend on one person; it depends on everyone. It mainly depends on men. Therefore, a woman cannot remain silent.

Nhandesy is concrete, practical, and lived. It is a body that occupies space, while Nhanderu is air. If men start disrespecting the land, it will be a high-impact disaster. The land must be well for us to step on it. The land is where we step, where the body lives. Therefore, greater and more concrete care is needed with Nhandesy’s body, so that women don’t get sick. “Not sick as in a sick body, but py’a tarowa—confused, terrified,” my grandmother would explain. If it is not disrespected, a woman’s body makes a better impact on the world. When Nhandesy gets angry, the world gets sick. If Nhandesy does not live in peace, the world will not live in peace, because she is the concrete land, she is Earth.

Understanding the meaning of arandu is also understanding our narratives, especially oreipyrã, which is the narrative of how the world came to be. With the Guarani understanding of the world’s origin, we share a collective memory, what we call a “collective education,” which allows our narrative to be incorporated. That is our way of telling others who we are. From this knowledge, new knowledge is built, such as Teko porã rã—our future well-being.

“I realized that school practices can cause perplexity, distress, and embarrassment to Indigenous children, who cannot understand the reasons why they are being disrespected.”

In my research, I try to report how I, as a Guarani woman, perceive the school system in the villages. School education is an external institution, accepted but not managed by the Guarani communities. Many memories of violence encouraged me to describe how children were treated when I was a student, and still are. Communities often complain about how the school institutions treat them. Since I was a child, I listened to and participated in the elders’ conversations about the nhandereko. I realized that school practices can cause perplexity, distress, and embarrassment to Indigenous children, who cannot understand the reasons why they are being disrespected. Mainly because they do not understand the language imposed on them and their kins, they find themselves sub-alternalized and dominated, unable to express themselves and live autonomously.

I remember when I started going to school. I was a child, I didn’t speak Portuguese, and I was scared. As it was mandatory, I had to be brave. I really wanted to learn how to read and write in order to show my parents and everyone else. I tried really hard, although I didn’t know any Portuguese. Today, I understand the anguish and the friction between Guarani education and school education. My hands would hurt from copying the whiteboard, but copying was not the worst part. The worst was not knowing what I was copying. We were monolingual children, who only spoke Guarani, copying useless words. These methods still endure in Guarani schools; they are still mondyi—scary.

Mbo’e—teaching and educating, is not only showing what is written on paper; teaching in Guarani means making together, and learning while practicing. The concept of mbo’e means to prepare for life by exploring the competencies of each individual’s teko, thus strengthening the knowledge the student brings to school. Children should not go to school to learn or to be guided, as if they were lost. They should go to school to reinforce their people’s knowledge, strengthen their cultural identity and mother tongue, and talk about their life experiences.

I agree that it is also important to know non-Indigenous history and to understand the juruá reko, but I realize that in the juruá perspective, “education” means something completely different than it means to us. The word comes from the Latin educere, which means literally “to conduct out,” or “to direct out.” The term in Latin is composed of the sum of the prefix ex which means “out” and the verb ducere, which means “conducting” or “guiding.” Even though we have some guaranteed rights, the school system in Brazil still amounts to a single system. Indigenous schools follow the same rules and precepts of the juruá schools, thus enhancing mechanisms that have for so long silenced us and distorted our traditions.

“The school can easily become one more instrument to deny us, if we don’t bother to say to the juruá that we exist.”

In 2004, I was invited to take on a mixed grade classroom in the Três Palmeiras village, in the state of Espírito Santo. In my opinion as a Guarani teacher, the school followed the Latin meaning of the word “education.” It is no accident that we are clashing with it. The school can easily become one more instrument to deny us, if we don’t bother to say to the juruá that we exist. We are making great efforts out of the fear of being excluded, rather than out of the hope of being included. We are surrounded by laws that try to protect us, but which also deny us.

When I was teaching, we had a very welcoming curriculum proposal, which allowed us to talk about our experience, our education methods, and whatever matters were important to us as Guarani people. In the mixed classroom in question, most of the girls were of menstruating age. For us, right after the first period, the girl needs to rest for at least three months—the rest time varies a lot from family to family. According to traditional Indigenous education, she must receive care from her family and take care of her own body during that period. This process is treated as a rite of passage. The girl rests her head and listens to her py’a—her feelings—so that her body and head will get used to being calm.

This special kind of treatment introduces a different kind of education. Even so, the teaching team questioned why the girls who were abiding by the ritual, and therefore were not present in class, were not being sent homework. I was outraged! That was when I understood how asymmetrical it all was. It was clear that they did not comprehend the young women’s resguardos—our costumes—as a form of education. However, they clearly thought that sending them random written homework was good teaching.

The different juruá knowledges are registered on paper; they are stationary, they are not following omyῐ wa’e (the flow) and guata (walking the path). For us Guarani, some school activities are not as important as the very significant period of the girls’ passage. What is on paper is not as important, because what has immediate effects on life are the day-to-day practices. We believe in our history because it teaches us to build teko porã, the “good living.” My grandmother used to say we should not believe in the world of paper, because writing has no feelings; it does not breathe, it is dead history. We have to be careful with paper, even though it is also part of our lives today.

All arandu—knowledge—regardless of where it comes from, holds fundamental values and ideas for each people or group and is important for a person’s formation. However, no knowledge should be treated as absolute, and no universalism should be imposed. There is not just one way of knowing, nor just one way of teaching and learning. The “truths” that juruá science claims to have discovered are reproduced in school, and students learn that they cannot be changed. This creates clashes, as for us the teko is dynamic. The collective wellbeing depends on each and everyone. As I understand it, teaching requires great effort in training the learner to deal with others and, often, to make sacrifices for others; this means loving oneself.

I challenged myself so that the wisdom of women would not fall into oblivion, moving them away from their teko. I challenged myself, even knowing that I would have to give up some of the customs of the Guarani women. It was necessary to direct myself to “cross the bridge.” Crossing demands greater attention, so as not to be deceived by the things on the other side, by the attractive images offered by the city and the many things that do not exist in the village. It is important to know the juruá codes, but it is even more important to strengthen oneself in the base so that we are not easily captured. Living and speaking the Guarani language is essential for keeping a path to return home, even if we must learn to speak another language along the way.

How to keep my roots, in a world of antennae? I remember these terms—“roots” and “antennae”—in the words of Professor José Ribamar Bessa, who taught at the Kuaa mbo’e training course for Mbya teachers. He used the image of a tree to talk about interculturality; about how it could be implemented in everyday life. The root would be our base, our origin. In my case, this is my traditional Guarani identity. My roots are in my grandmother’s memory, my parents’ knowledge, and what I kept with me. The antennae would be what comes from the outside, which is not part of the Guarani system.

“It is possible to keep our roots in place, even living in the city, despite the friction between worlds.”

In the journey between the roots and the antennae, it has not been easy to move from one culture to another. Thankfully, I have a firm, strong base, so I wouldn’t get lost easily between the two worlds. A strong identity at the root can overcome obstacles. Speaking of my trajectory, xerapixa kuery’i, from a woman to other women, I can contribute with other courageous py’a guasu women, so that we can continue achieving what we desire. It is possible to keep our roots in place, even living in the city, despite the friction between worlds. I seek strength in the words I heard from my djaryi.

This is how I introduce myself, as kunhã py’a guasu, a woman with a feeling of courage. My Guarani name is Ara Rete, “strength of the day/sky.” I am a person from the inside out, and sometimes from the outside in. Beauty is in my essence, in my language, driven by the memory of my grandmother. I believe in collective memory, not just my childhood memories. When I remember things, I do so in order to think. I am here, and I will live, fall, get back up, walk, and move on. I carry in me the strength of Nhandesy. Tomorrow, I’ll have reinvented myself.

I constantly reinvent myself when I encounter a different language, or a teko I don’t know. I lose myself; I find myself. A foreign language and a foreign teko ask a little more from me. Good thing I am complex, I am a mixture—a Guarani woman who sometimes looks like a juruá woman. It’s my form of resistance. I see myself as a bridge. I exist between the village and the city. This is not an easy task for me, but it is a way I find to be able to continue dialoguing with these two worlds. I use elements of the Portuguese language, but I do not lose my essence. My reinvention is an element of resistance that I use to strengthen myself and add to my experience.

“KUNHÃ PY’A GUASU” was originally published in Portuguese in December 2023 by the Brazilian publishing platform Piseagrama.

Sandra Ara Benites (she/her) is an anthropologist, educator, curator, and cultural advocate from the Brazilian Guarani Nhandewa indigenous group. She holds a Ph.D. in Social Anthropology from the Federal University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRJ), Brazil. She was an assistant curator at the São Paulo Museum of Art (MASP) and is currently the Director of Visual Arts at the National Arts Foundation (Funarte), Brazil.

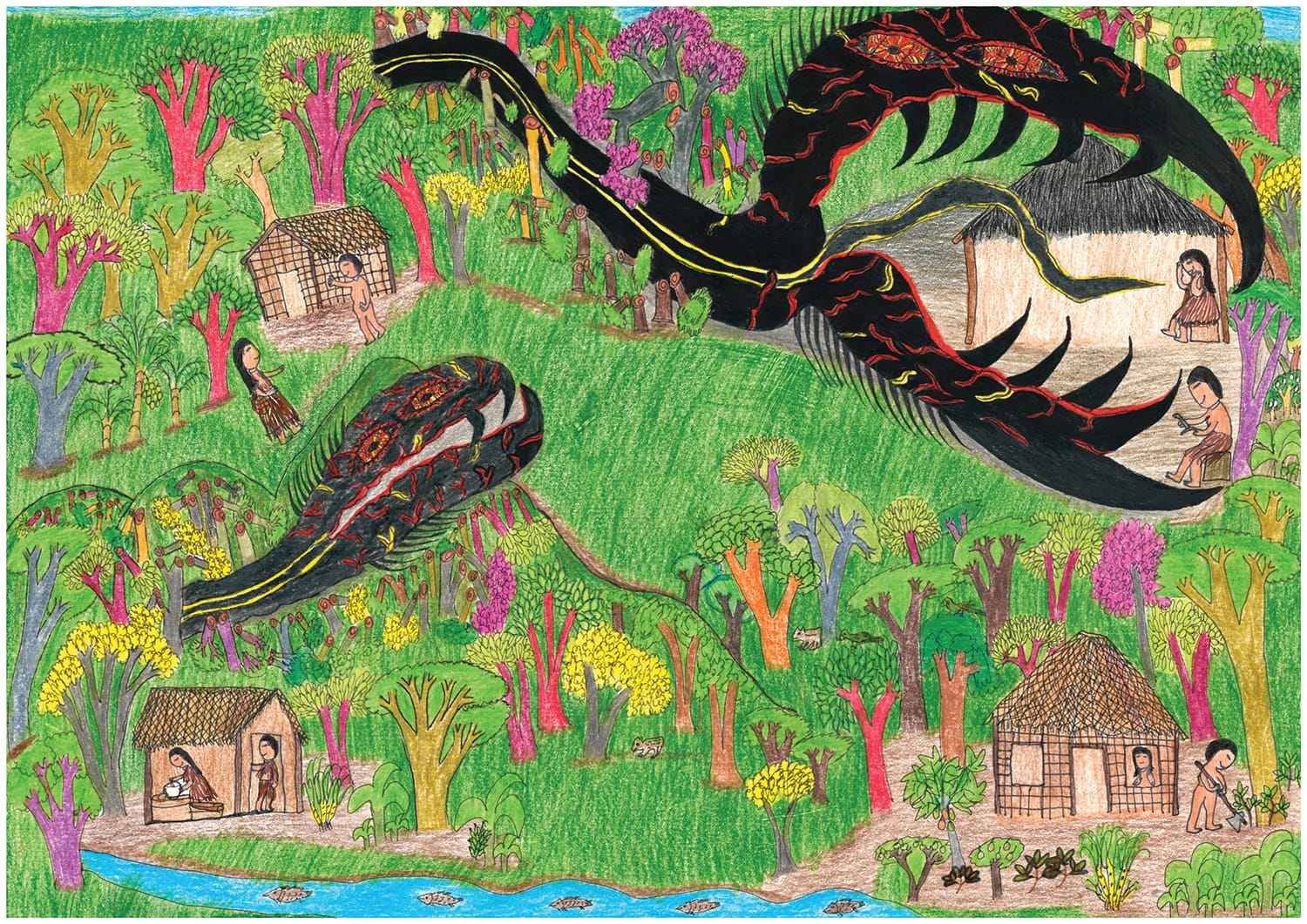

Title image: from the series Tehêy Sol, Vento, Chuva, Lua (Tehêy Sun, Wind, Rain, Moon) by Lica Pataxoop

Liça Pataxoop (she/her) is an artist and educator at the Muã Mimatxi Indigenous School, in Minas Gerais, Brazil. She belongs to the Brazilian Pataxoop Indigenous group.

Translation: Brena O’Dwyer.

Brena O’Dwyer (she/her) is a Brooklyn-based Brazilian professional with a multidisciplinary background. She holds a PhD in Anthropology and is the author of the poetry book As Ilhas. Brena was the editor of O’Cyano magazine and worked as a translator. Now in a new chapter of her life, she works as a software developer.

TRAVESSIAS— CROSSINGS is a collaboration with the Brazilian publishing platform Piseagrama, working together to translate into English a series of urgent Afro-Brazilian, indigenous and LGBTQIA+ voices, originally published in Portuguese by Piseagrama. The project aims to function as a transnational meeting point across cultural, geographical, cosmological, and linguistic borders.