This text was originally published on Pride Day 2019. It was translated into English, edited, and expanded to be republished on International Trans Day of Remembrance and Black Awareness Day in Brazil 2020.

Narrative disputes. Misconceptions. Misunderstandings. A lack of historical records. Continual erasure. History is designed by the people that tell it, and timelines represent only one strand of a story—too often they favor the same one, over and over. When only one story is repeated, stereotypes are perpetuated, forming an incomplete picture of a history that’s far more complex and nuanced. In Brazil, a timeline that frequently gets forgotten and suppressed is that of the LGBTQIA+ movement—and within that it is especially the perspective of trans people that goes missing. For this to change, we need to shape our own histories into existence. We need to create our own timelines.

Although pioneers in the fight for LGBTQIA+ rights, trans people have always suffered from historical erasure. One of the most prominent examples of this are Marsha P. Johnson, Sylvia Rivera, and others who were central to the uprising that erupted out of a police raid of New York’s Stonewall Inn in 1969. While not the first of its kind in the United States, the Stonewall revolt became a catalyst for an intensifed LGBT organizing at the time, often referred to as the gay liberation movement, and a beacon of pride for the wider and still diversifying LGBTQIA+ political efforts of today. However, even now, after the event’s 50th anniversary has passed, media outlets and historical accounts often fail to contextualize trans people’s vital role in this momentous event and the movement in general. Similarly in Brazil, I witness this historical erasure of trans people all around.

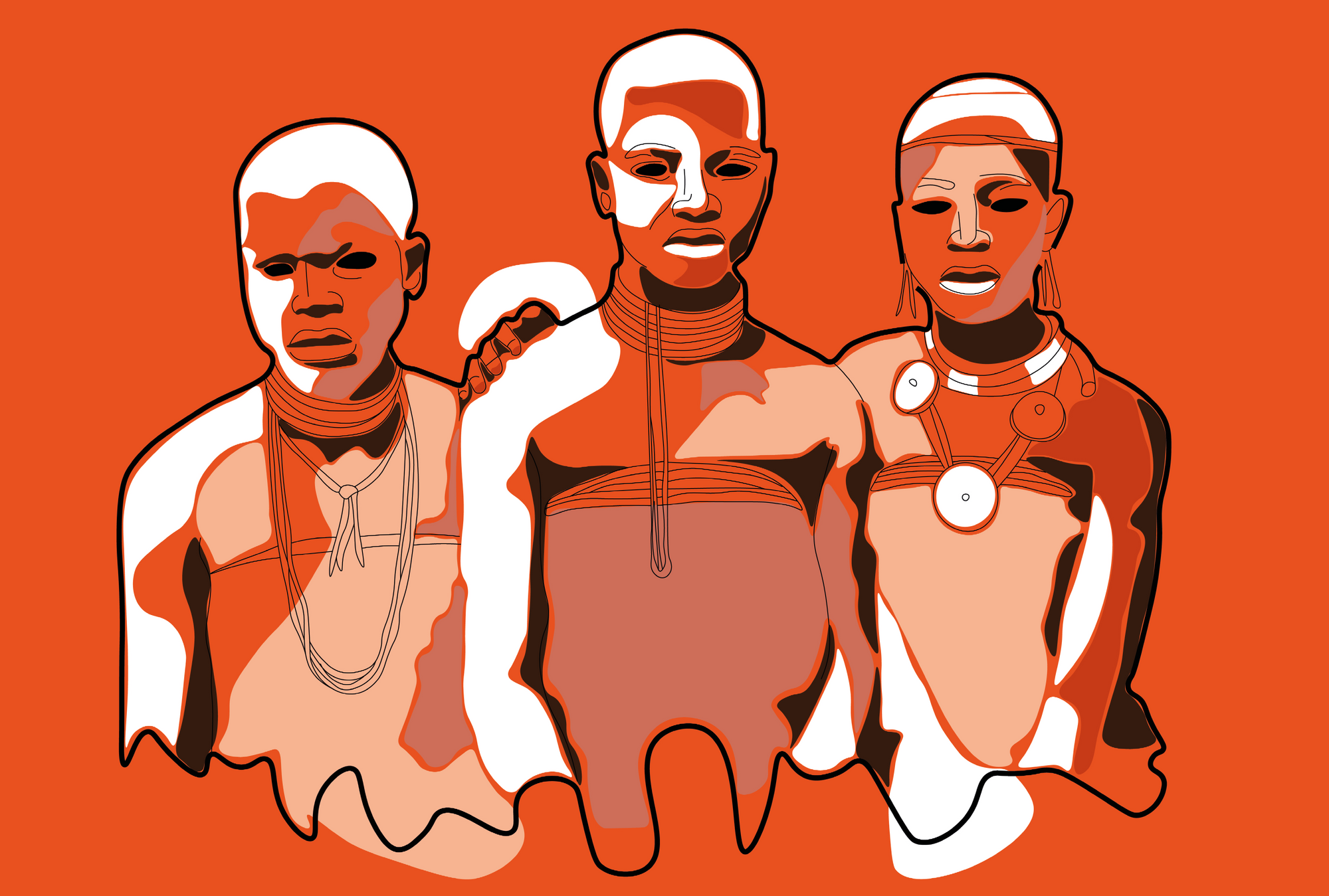

What you are reading here started last year, when I decided to organize and design a timeline of important events for the community that places trans people—and the unique gender identity of travestis—at the center of the story. Travesti is a spectrum of gender identities historically and culturally rooted in Brazil and Latin America, for which no direct translation can be found. As with other non-Western gender identities, travestis do not easily fit into a Western taxonomy that separates between biological sex and social gender. Travestis continue to be one of the most marginalized and vulnerable groups in Brazilian society.

On the occasion of the International Trans Day of Remembrance (TDoR), held every year on 20 November, the Transrespect versus Transphobia Worldwide (TvT) research project publishes updated data gathered through the Trans Murder Monitoring (TMM). This year, the project reports a total of 350 trans and gender-diverse people murdered between 1 October 2019 and 30 September 2020 worldwide, representing a 6% increase in reported murders from last year. The number of cases of lethal violence may be even higher, due to the high rate of underreporting and difficulties in data collection. Of the known murders, the majority, 43% to be precise, occurred in Brazil—a percentage that hasn’t changed much over the past decade. According to ANTRA, the National Association of Travestis and Transsexuals of Brazil, the average age of those murdered in Brazil is 26 years old, and the chance of a transgender person being murdered in Brazil is 9 times greater than in the United States. Data from recent years further showed that 82% of the trans population murdered in Brazil is Black. Now more than ever, we need to continue the effort of rebuilding our own history and bring attention to our lives. There really is no time to lose.

A lot has, however, already been lost to time. There is one small historical trace that would allow us to begin a timeline of trans and travestis history in Brazil as early as 1591, when the first known travesti person in the country’s history passed away, an enslaved woman from West Africa called Xica Manicongo. In Brazil, she was the property of a shoemaker in the city of São Salvador, today Salvador, the capital of Bahia. Under the Portuguese law of colonized Brazil at the time, social rules of dress were strict, as was the forbidding of an “inversion” of gender. Sodomy was deemed a crime against the crown, and those found guilty were burned in a public square. Xica was accused of sodomy, and forced to give up her gender identity and sexual orientation. Her history is one of gaps and silences—the narrative of her life and death is in constant dispute.

Another known central figure is that of Madame Satã (1900-1976), considered the first travesti artist in Brazilian history. Despite reserving moments of femininity for the stage, Madame Satã’s self-identity has been described by historians as ambiguous and fluid. Born twelve years after abolition in Brazil, a descendent of slaves, Madame Satã was exchanged for a mare at age seven. Madame Satã ran away to Rio de Janeiro at age 13, finding work as a security guard, waiter, cook, and more while discovering an outlet in cabaret. Offensively referred to as a “doll” and “faggot,” Madame Satã conjured the courage to appropriate those terms and wear them with pride while defending those who needed it. Madame Satã took care of prostitutes, queer people, and kids from the Lapa region, which is the bohemian center of Rio. This desire to protect would stay with Madame Satã until their end. Between their 26 prison trials that resulted in a total of almost 28 years in jail, Madame Satã adopted five children.

The following timeline starts in the 1950s and is just one way of looking at a history that certainly has other lenses to peer through. Everything mentioned was considered from the perspective of the struggle of trans and travesti people—a struggle that is still ongoing, in Brazil and beyond.

1959: The first gender confirmation surgery in the country took place in Itajaí, Santa Catarina, in the South of Brazil. The story of Mário da Silva, an intersex trans man, became widely known through the magazine O Cruzeiro. 28 years prior, in pre-WWII Germany, Lili Elbe was the first known person in the world to undergo gender confirmation surgery.

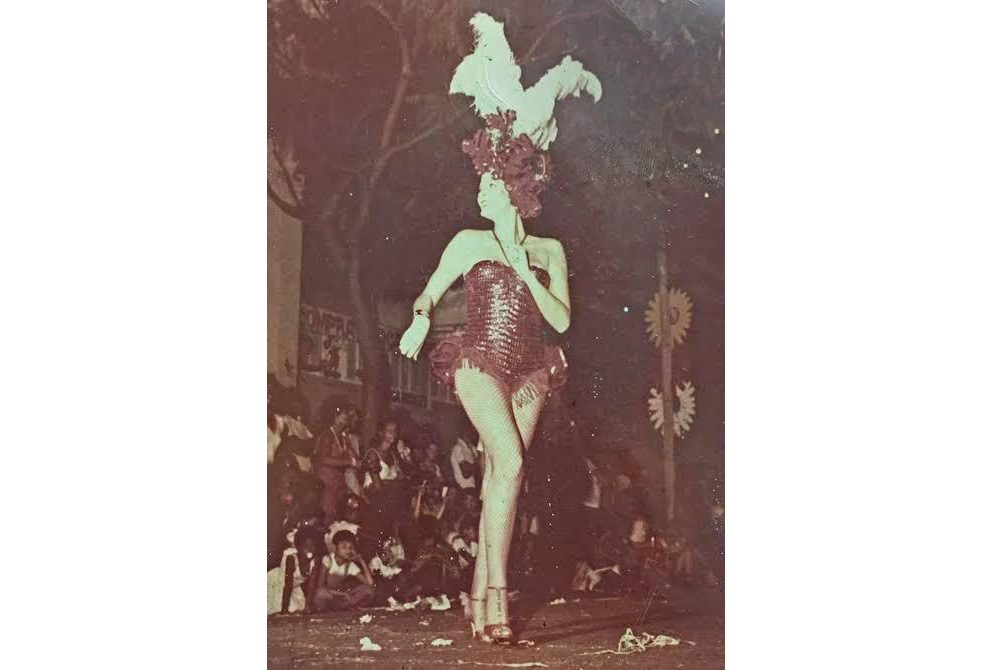

1960s: The Divinas Divas were a group of travestis that performed in plays and musicals, as composed by Rogéria, Jane Di Castro, Divina Valéria, Camille K, Fujika de Halliday, Eloína dos Leopardos, Brigitte de Búzios, Marquesa, among others. Famous travestis ever since the 60s, their story became a documentary film in 2016.

1962: Turma OK, the first registered LGBT group in Brazilian history, was founded in the city of Rio de Janeiro, led by Agildo Bezerra Guimarães. The social club still exists today—one of the oldest LGBTQ+ clubs in the world—and it maintains its ballroom traditions.

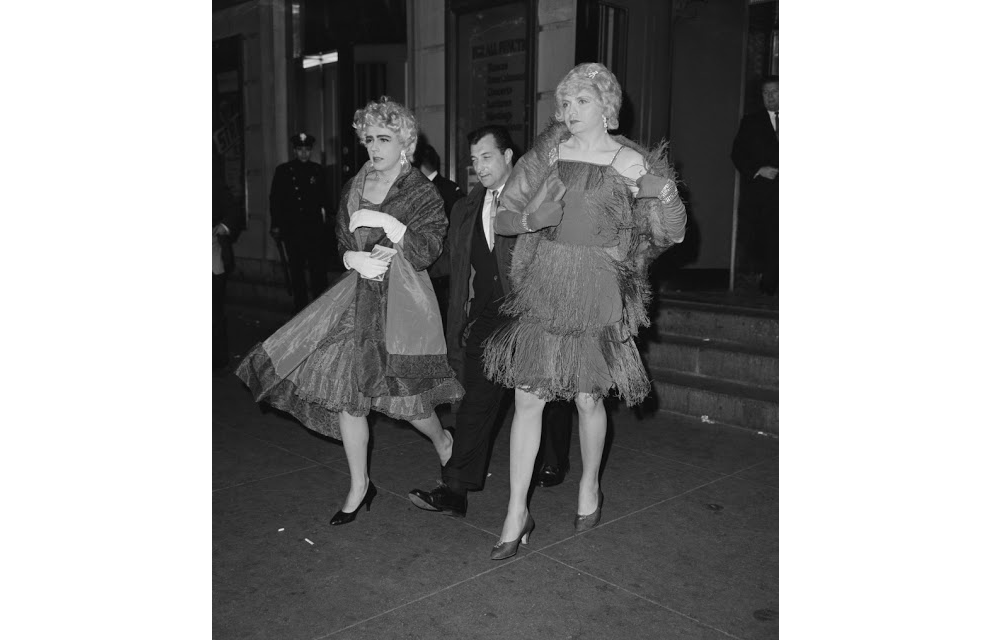

1970s: After seizing power in 1964, the country’s military dictatorship hardened after 1968. The LGBTQ+ community was deemed “perverted,” becoming the target of government repression and persecution (as was the also the case for the Black community).

1971: The first gender confirmation surgery of a trans woman, named Waldirene, was performed at Hospital Oswaldo Cruz, in São Paulo. The doctor who conducted the operation, Roberto Farina—at that time one of the most important plastic surgeons in the country—was convicted by the Federal Council of Medicine for “bodily injury.” At the time, surgeries of this type were prohibited.

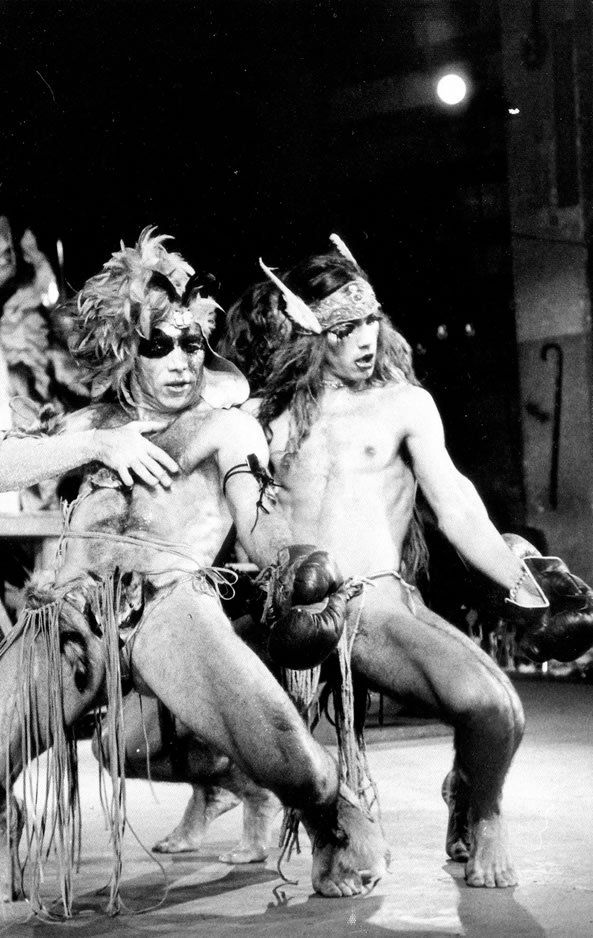

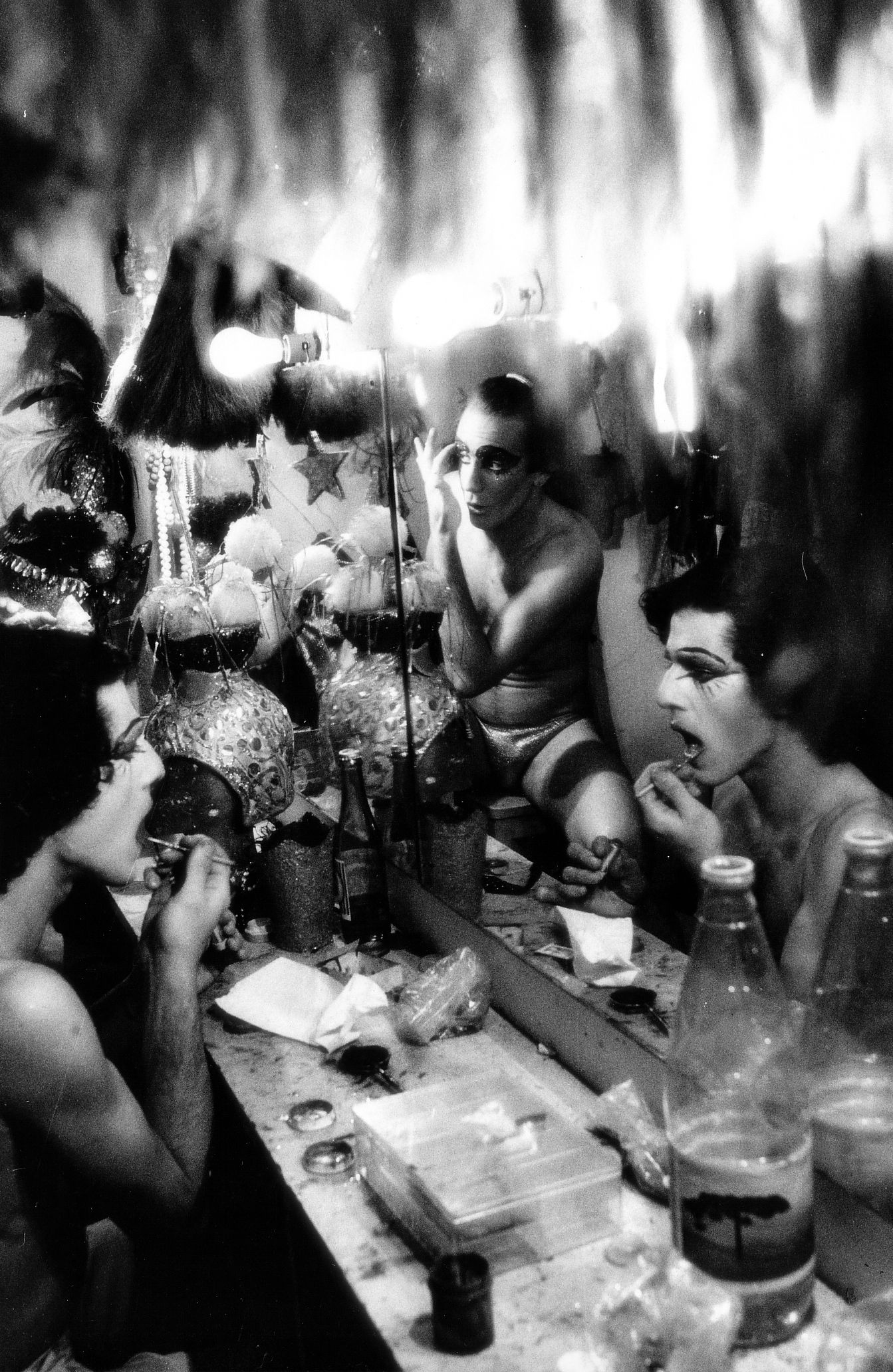

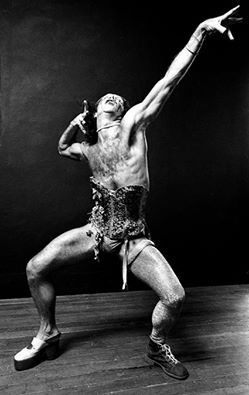

1972: Dzi Croquettes formed, an irreverent theater and dance group from Rio de Janeiro, dedicated to the collective creation process and experiential theater. The group stood out for their exuberant look—heavy makeup, high-heeled shoes, and feminine clothing—paired with purposefully hairy legs and beards. Their androgyny shocked the military regime and the group was censored. But Dzi Croquettes became a symbol of the counterculture, of social transformation, and breaking taboos.

1976: From 1976 onwards, the São Paulo police began to systematically persecute trans people and travestis. The officer Guido Fonseca was responsible for the criminology research that informed persecution policies: He determined that every travesti should be taken to the police station, registered, and photographed, “so that judges can assess their dangerousness.”

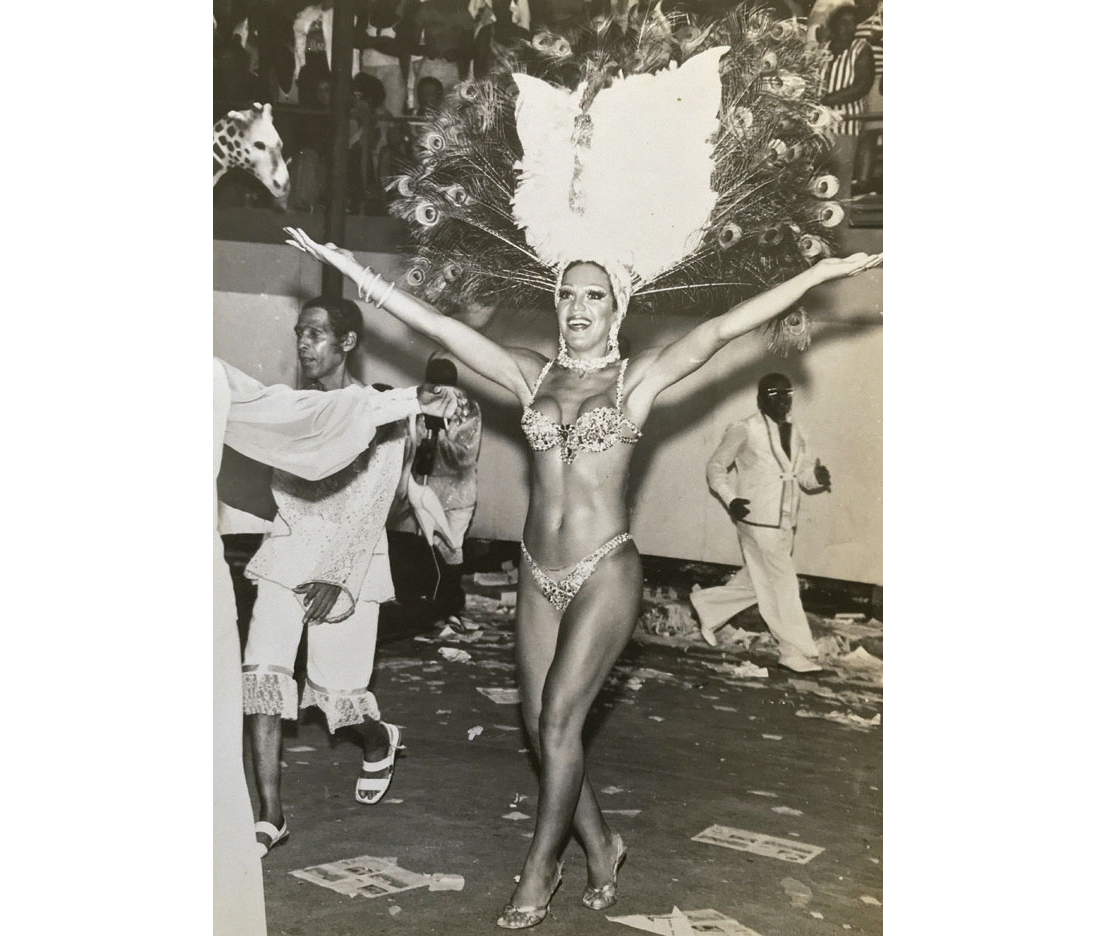

1976: At the invitation of “carnavalesco” Joãozinho Trinta—the organizer of the samba school Beija Flor’s samba parade—the travesti Eloina dos Leopardos became the first woman in the country ever to hold the position of “Queen of Drums.” She paraded in the carnival of Rio de Janeiro until 1978.

1977: Claudia Celeste (1952–2018) was announced as the first travesti to act in a Brazilian soap opera. Born in Rio de Janeiro, Celeste began her acting career in the 1970s, after working as a hairdresser. Her participation in the show was canceled though, after the press had already celebrated her as the first travesti on TV. Ten years later, Celeste was cast in Olho por Olho on the former TV network Manchete, finally becoming the first travesti to act in a soap opera.

1978: SOMOS, a Homosexual Affirmation Group, formed, constituting the first Brazilian group to defend LGBT rights.

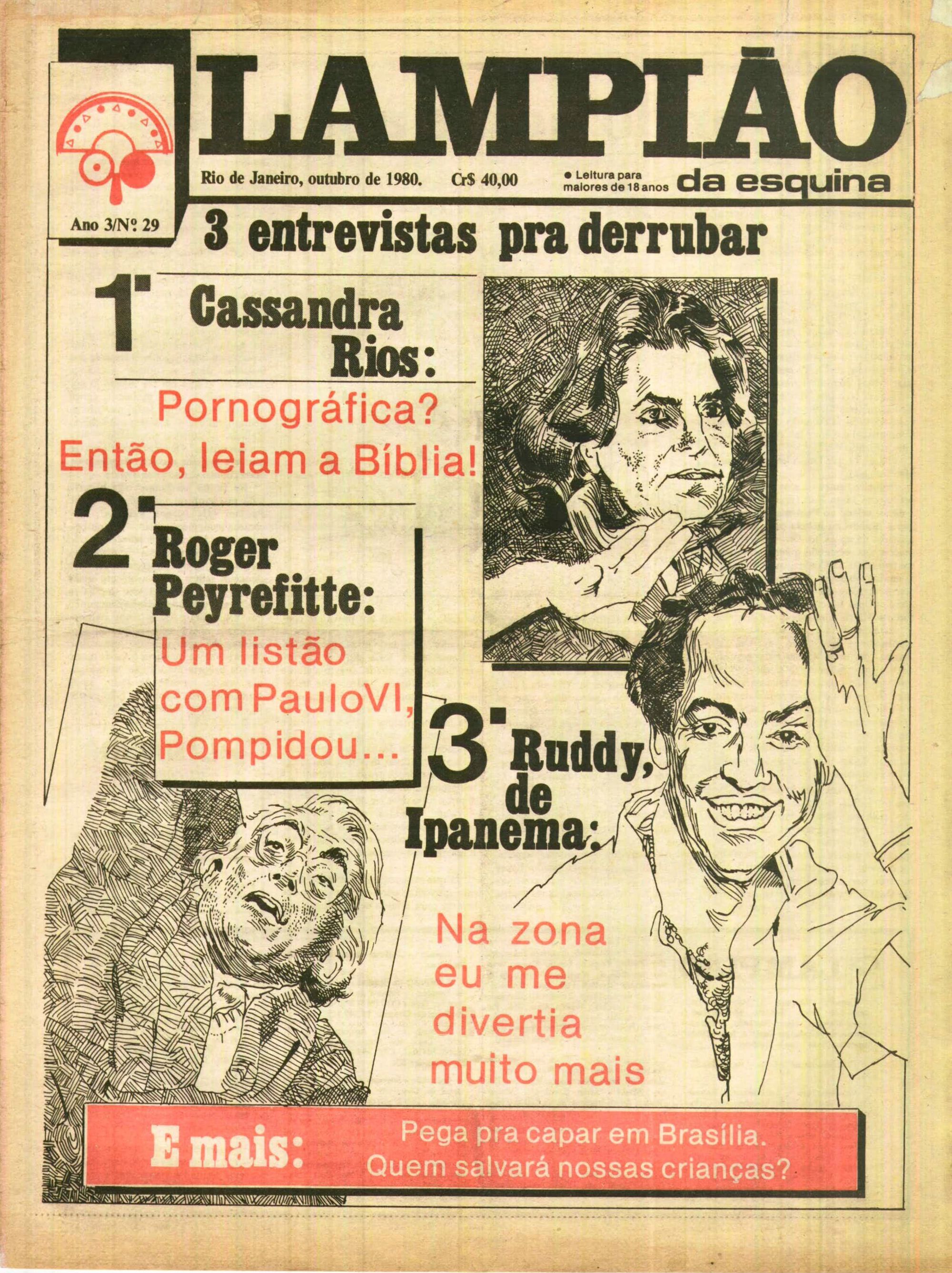

1978: Lampião da Esquina was launched, a homosexual newspaper born out of the context of the alternative press. It emerged during the years that the censorship of the military dictatorship had begun to ease and circulated until 1981.

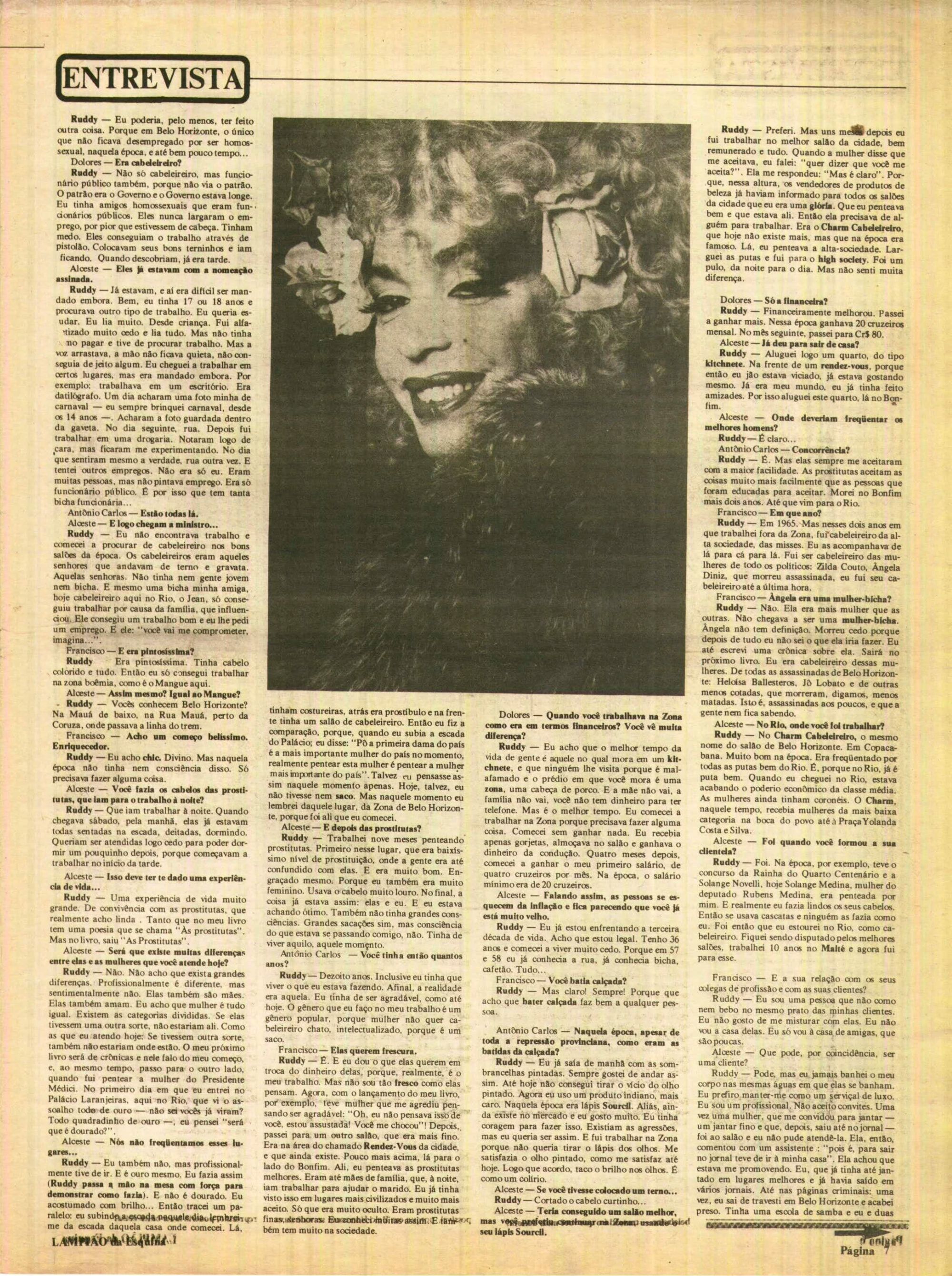

1980: Eu, Ruddy (I, Ruddy) was published, the first book written by a trans person in Brazil. Ruddy Pinho was one of the most prestigious hairdressers in the country, and has now published seven books to date and collaborated on two more.

1981: The pamphlet Chana com Chana was launched, as produced by the Lesbian-Feminist Action Group (GALF), and often sold at a bar named Farro’s. While the bar was often frequented by lesbians, the owner decided to ban the pamphlet’s sale. On August 19, 1983, the bar was occupied by LGBT groups, femininsts, and political activists, who revolted against discrimination. The bar publicly apologized. Chana com Chana then circulated until 1987.

1982: The first HIV case in Brazil was officially diagnosed and recorded in São Paulo. The phrase “Disease of the 5H” was temporarily adopted by officials in reference to HIV; the five “H’s” standing for homosexuals, hemophiliacs, haitians, heroinologists (users of injectable heroin), and hookers.

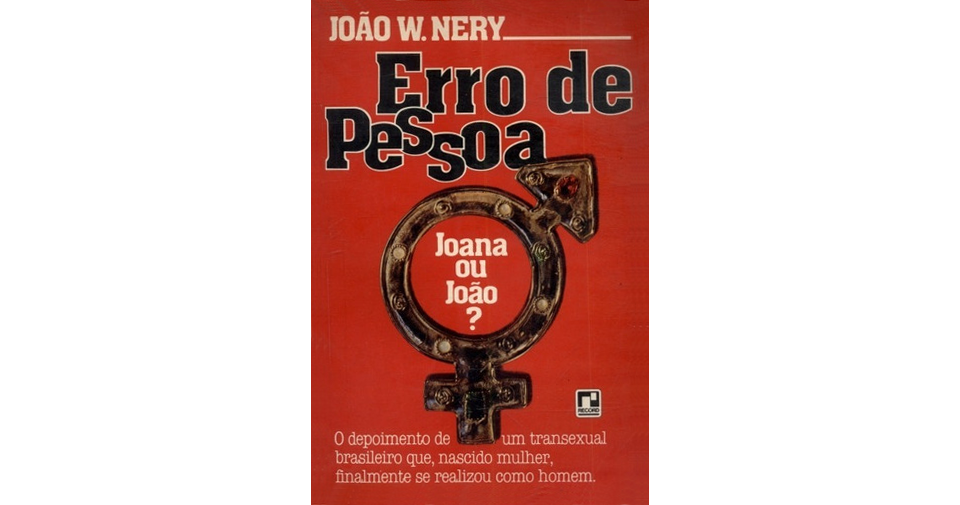

1984: Erro de Pessoa (Human Error) was published, the autobiography of João W. Nery (1950–2018), and the first book written by a trans man in Brazil. The book spoke about his life, and it later served as a source for his famous memoir, Viagem Solitária (Solitary Voyage), which was published in 2011.

1984: Roberta Close (1964–), a pioneer trans women who spoke openly about her gender confirmation surgery, was elected the most beautiful woman in Brazil. She was also the first trans model to pose for the Brazilian edition of Playboy magazine, appearing in its May 1984 issue, which sold 200k copies in three days—an unprecedented feat for the publication.

1985: The Federal Council of Medicine de-pathologized homosexuality in Brazil. This was five years before the international de-pathologization from the World Health Organization, which took place on May 17, 1990.

1985-86: The Ministry of Health created a national STD and AIDS program in response to the AIDS epidemic. This happened shortly after the country returned from military dictatorship to democracy. Only four cases of AIDS had been registered.

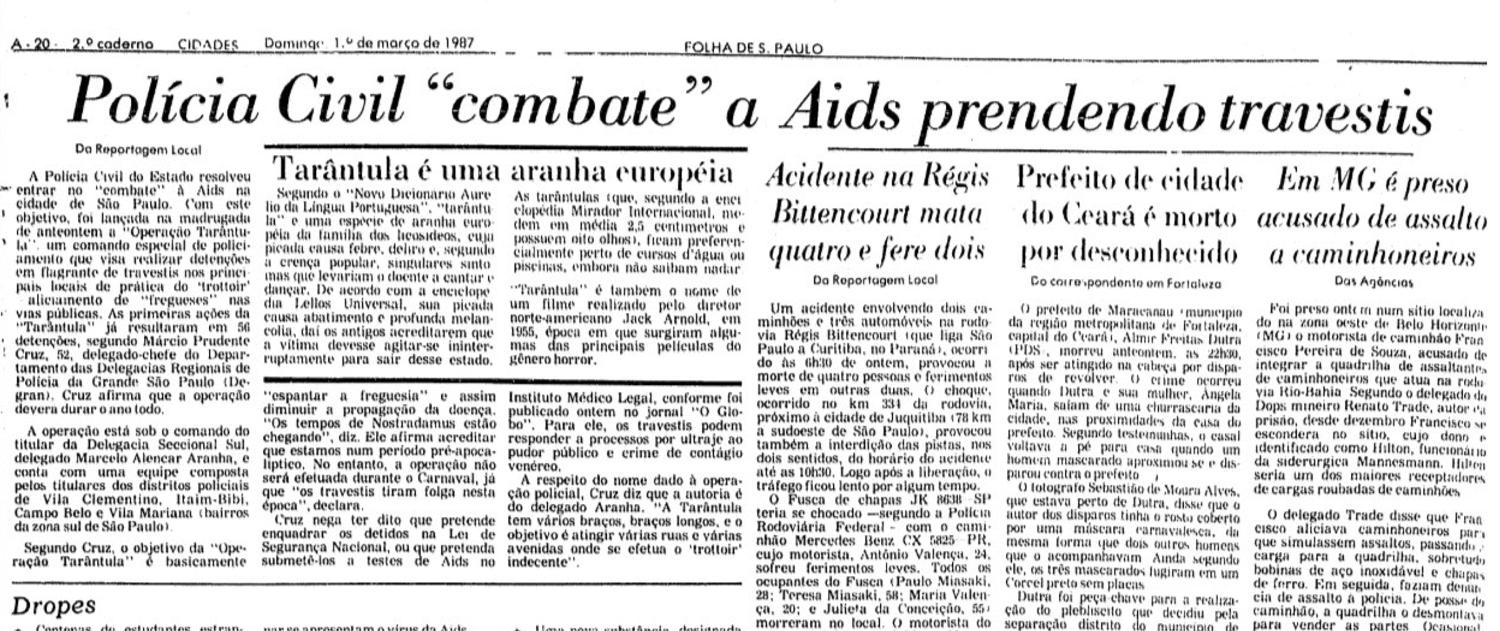

1987: The São Paulo police started “Operation Tarantula,” with the goal of arresting travestis sex workers on the streets of the city. On its first day, 56 people were arrested in order to, as newspaper headlines described, “combat AIDS.” Márcio Cruz, the chief delegate at the time, said that the city was experiencing “a pre-apocalyptic period” and that travestis were an “outrage in public modesty,” responsible for a “crime of venereal contagion.” The name of the operation was chosen because, like a spider, it would have “several arms, long arms.” More information about the events be found in the (Trigger Warning! discrimination, violence) documentary Hunting Season. The operation was quickly suspended thanks to the efforts of a female city councillor. However, this police action spurred anti-trans and anti-gay violence throughout the nation. After the operation, the number of murders of travestis spiked.

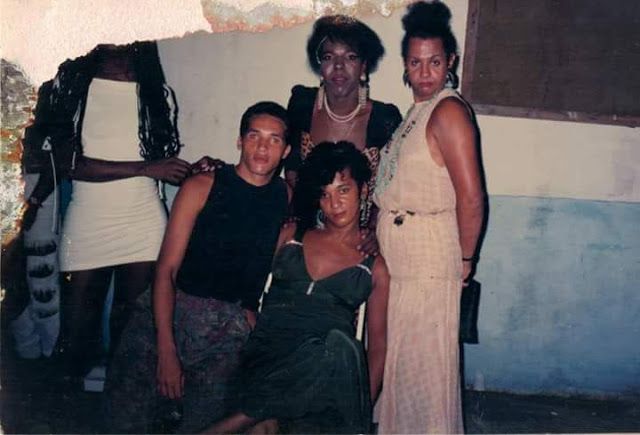

1992: ASTRAL, the Associação das Travestis e Liberados, was founded, the first institution focusing on trans rights in the country. Created by Jovanna Baby, Elza Lobão, Josy Silva, Beatriz Senegal, Monique do Bavieur, and Claudia Pierry France, ASTRAL was born from the need to organize trans people and travestis in response to the lack of access to health services, and to combat police violence. The latter was especially important for those in the traditional places of sex work in Rio de Janeiro.

1992: Katia Tapety was the first transgender person to become an elected official in Brazil. A resident of the municipality of Colônia do Piauí, in the northeast of the country, Tapety was elected city councilor three times. She was president of the city council between 2001–2002, and in 2004 she was elected vice-mayor.

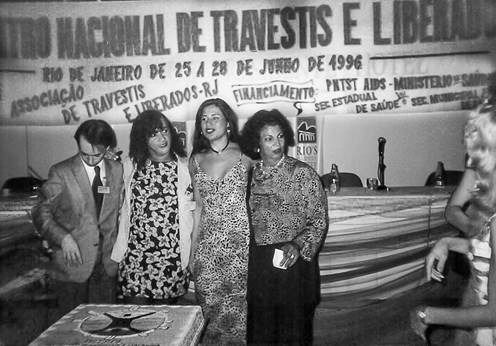

1993: The First National Meeting of Travestis e Liberados ENTLAIDS, which worked in AIDS prevention, was held in the city of Rio de Janeiro, and organized by ASTRAL. It was especially important due to its involvement of representatives from several states.

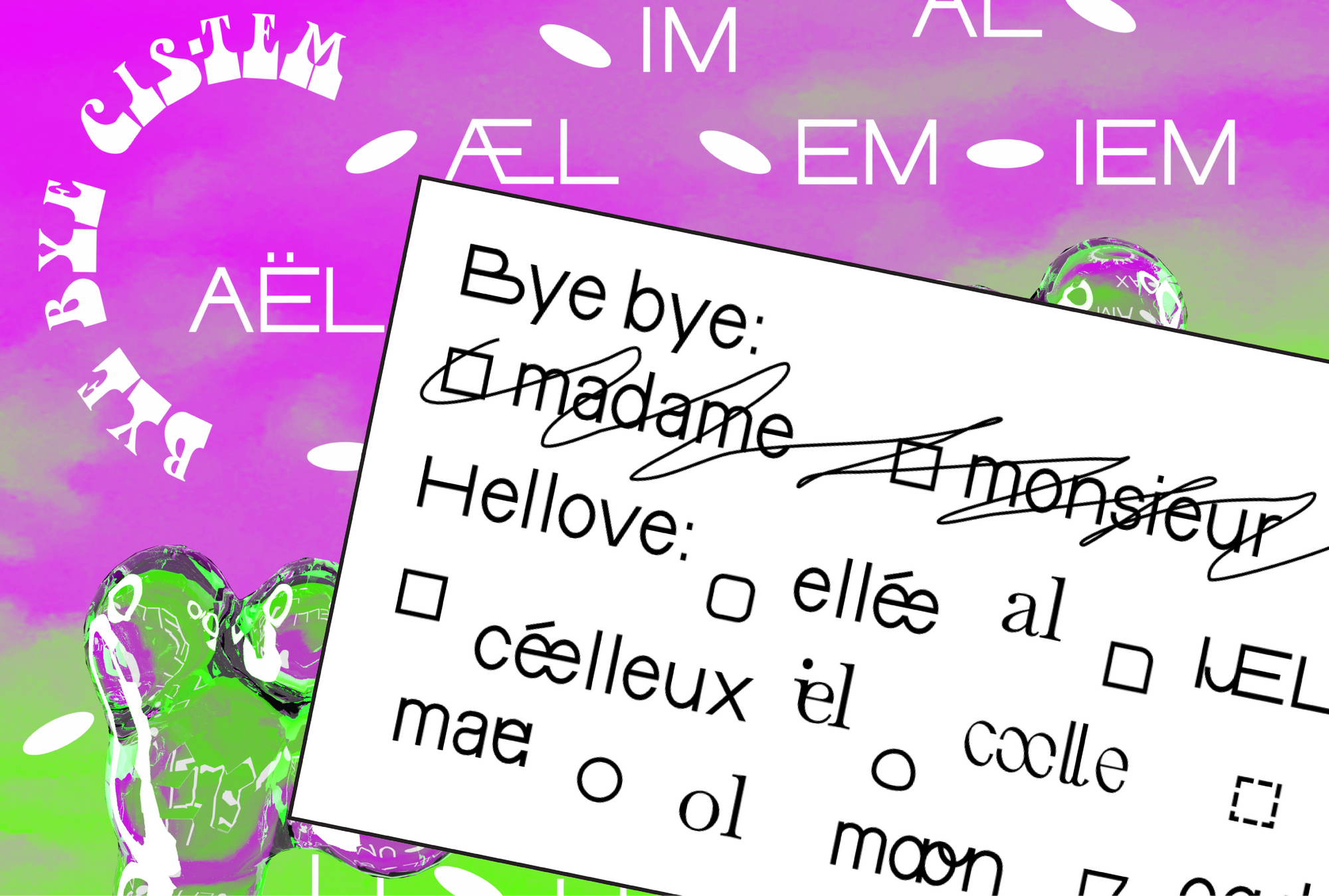

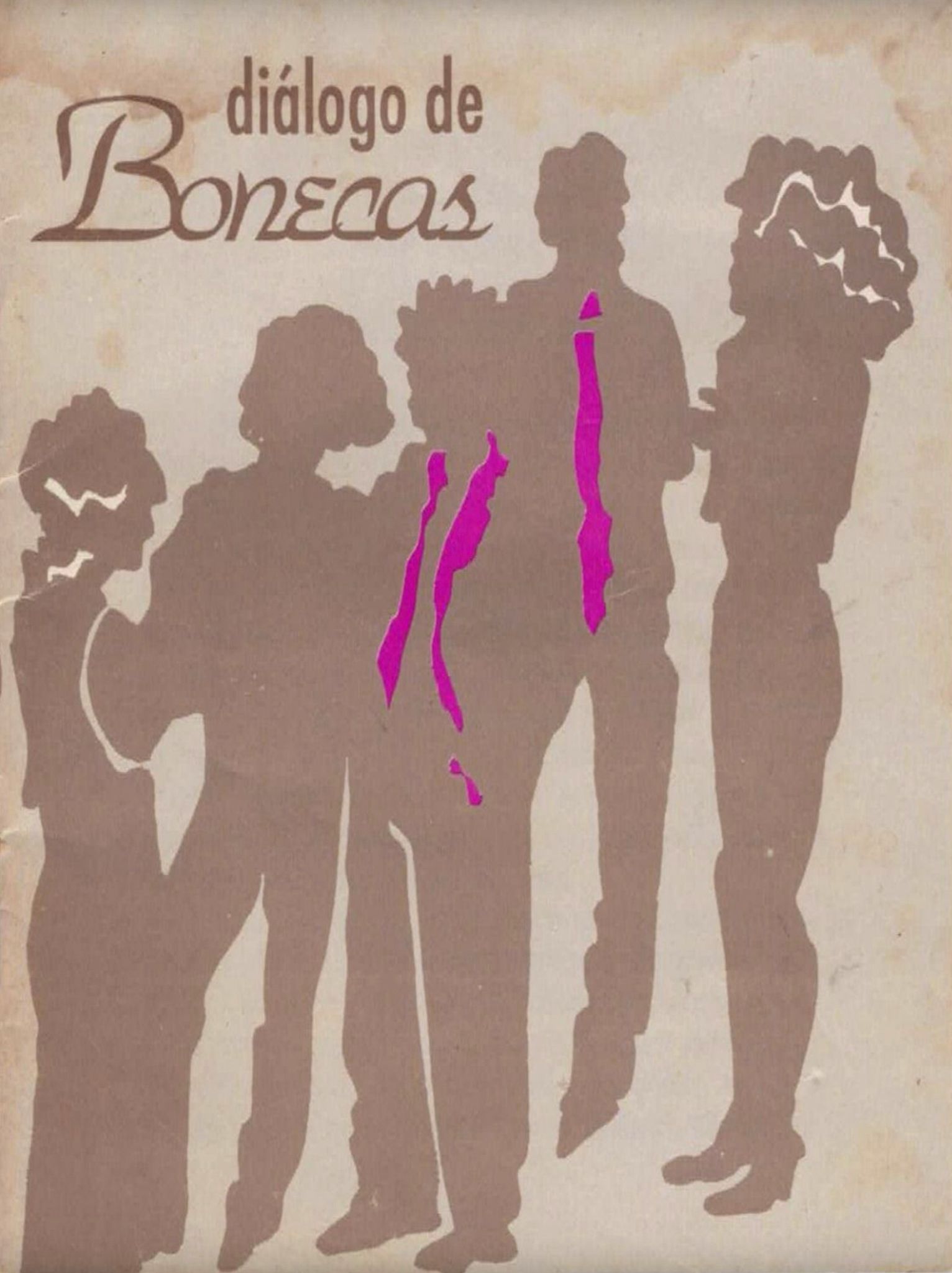

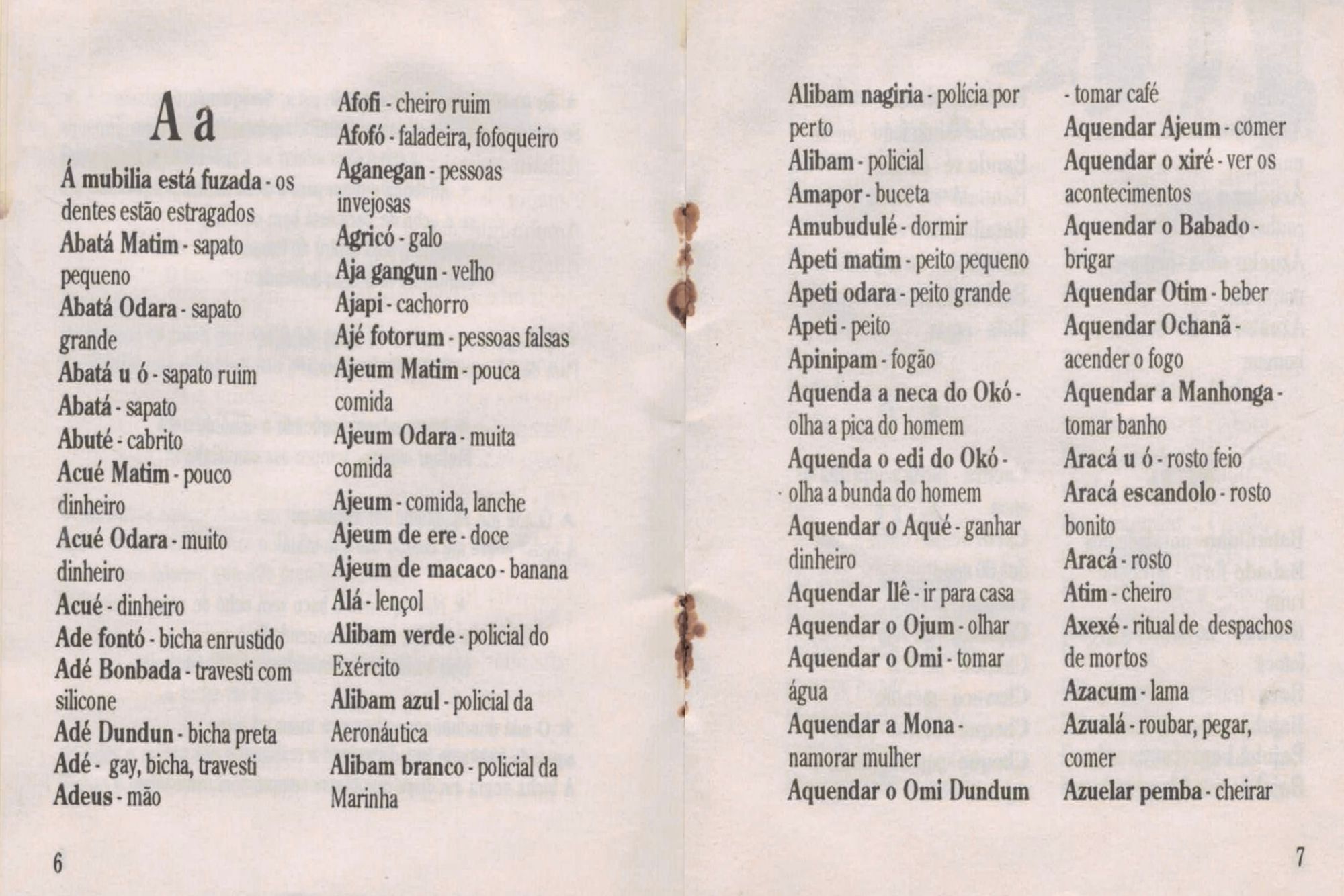

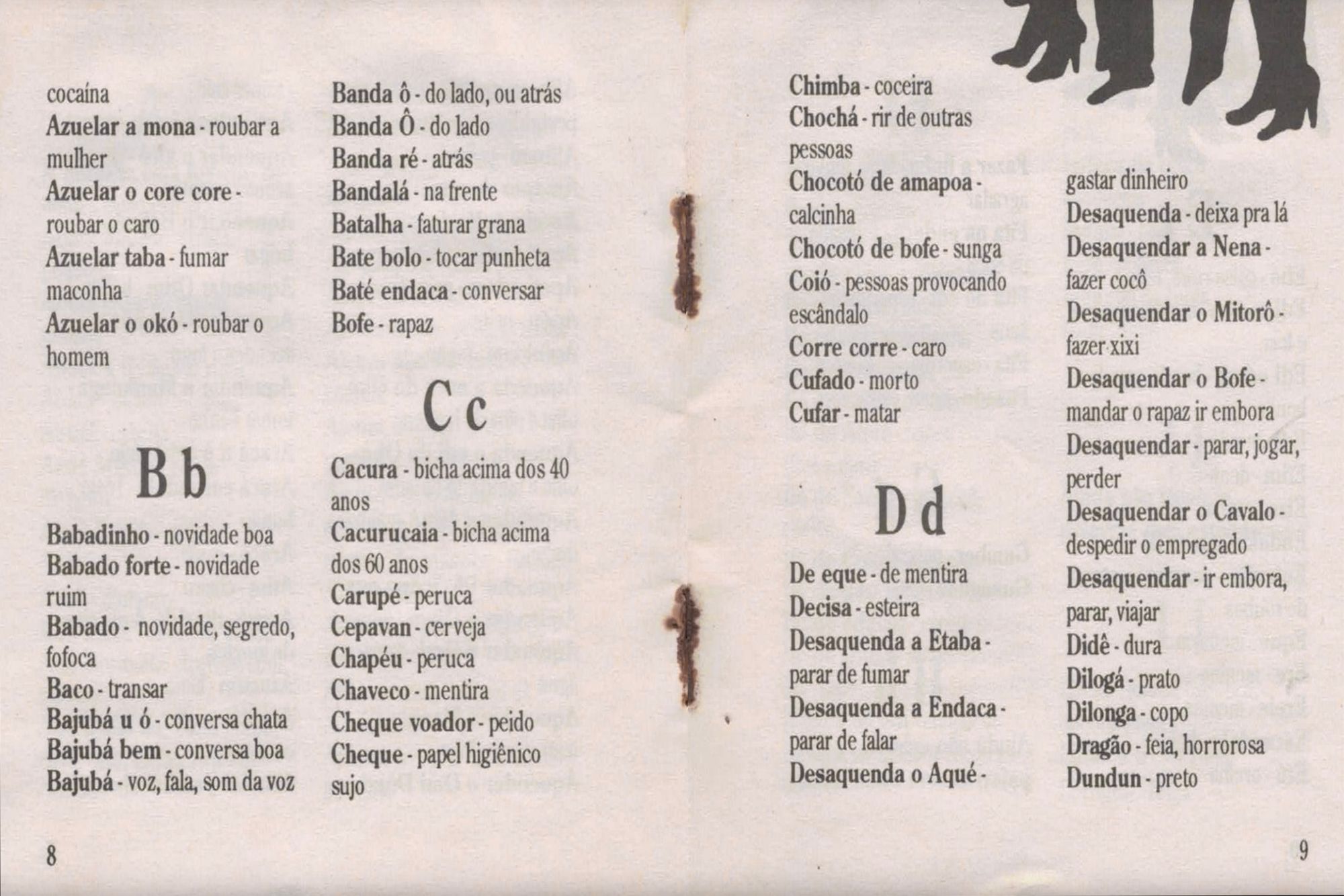

1995: The first Trans-Pajubá dictionary was published. Pajubá is a Brazilian cryptolect, or secret language, that integrates words from West African languages into Portuguese. It was used by the LGBT community during the country’s military dictatorship, as a code for safer communication. Entitled Diálogo de Bonecas (The Dialogue of the Dools), the dictionary of pajubá was specific to travestis; a language for women who lived from night prostitution, and used to defend themselves from attacks from the society and police.

1995: The first LGBTI+ Pride Parade in Brazil took place on June 25, 1995, in Rio de Janeiro, on the occasion of the 17th International LGBTI+ Association World Conference. Held in a hotel in Copacabana, the conference was attended by 1,800 representatives from 40 countries. The following Pride Parade was organized by Grupo Arco-Íris with Grupo Atobá, 28th June, Faces and Crowns, DELLAS Movement, United Astral Group, Triangulo Rosa Group, and NOSS among others. It brought together Brazilian people from all across the country, as well as international activists, culminating in 3,000 people celebrating on the streets.

1995: The organization RENATA/ RENTRAL was founded, which would later become ANTRA—the first national network of travestis and trans people in Brazil.

1997: The Federal Council of Medicine authorizes, on an experimental basis, the performance of gender confirmation surgeries, specifically vulvoplasty, phaloplasty, and/or complementary procedures on gonads and secondary sex characteristics. SUS, Brazil’s publicly funded, universal free health care system, starts to offer gender reassignment surgeries.

2002: TULIPA, which stands for “Trans Women United in the Relentless Fight for AIDS Prevention” was launched, a national project that championed the political formation of travestis and trans women. The program sought to identify and train new leaders to help guarantee rights for travestis and trans people. Several key institutions and activists emerged from the TULIPA project.

2004: For the first time in history, travestis and members of the trans community discussed with the federal government the creation of a national campaign to fight their discrimination. The National STD/AIDS Program was co-created with ANTRA and launched in the National Congress with the campaign “Travesti and Respect: it is time for the two to be seen together” on January 29, 2004. That date was later decreed by the board as the National Day of Trans Visibility.

2004: The program “Brasil Sem HOMOFOBIA” (Brazil Without Homophobia) was launched, based on a series of discussions between the Federal Government and civil society (non-governmental organizations, among others). Its objective was to promote citizenship and human rights for lesbians, gays, bisexuals, travestis and trans people.

2008: The Ministry of Health incorporated gender confirmation procedures for transgender women into the SUS, the Brazilian Unified Health System. The measure was significant for the trans population, as it recognized bodily transformations as a health need.

2008: The first National LGBT Conference took place, a historical landmark in the fight for citizenship and human rights for the LGBTQIA+ population. It was themed “Human Rights and Public Policies: the way to guarantee citizenship of Gays, Lesbians, Bisexuals, Travestis and Trans people.” This event was preceded by numerous state conferences and countless preparatory meetings at the municipal and regional levels.

2009: The SUS, Brazilian Unified Health System, allowed patients to use their social name. A social name is the name which travestis and trans people want to be known as, in contrast to their officially registered name, which does not reflect their gender identity. Through having social names respected in this way, more trans people started to access the health system.

2010: The Federal Council of Medicine removed the classification of “mutilation” from gender confirmation surgeries.

2010: The Federal Government, then presided by Luís Inácio Lula da Silva, created the National Council to Combat Discrimination and Promote the Rights of Lesbians, Gays, Bisexuals, Travestis, and Transsexuals (CNCD/LGBT).

2011: Brazil’s Federal Supreme Court recognized civil unions for homosexual couples—years before most European countries and also the USA. In a unanimous decision, the justices stated that long-standing homosexual couples merit the same rights and obligations that Brazilian legislation grants to heterosexual couples.

2012: Luma Nogueira de Andrade becomes the first travesti in Brazil to receive a doctoral degree, with a dissertation titled “Travestis at school: subjection or resistance to the normative order” and defended at the State University of Ceará. Luma also became the first travesti to get a permanent professorship at a public university. She’s currently a professor at UNILAB, the University of International Integration of Afro-Brazilian Lusophony.

2013: The Ministry of Health expanded the SUS “Transsexualizing Process”—what the Brazilian government calls the medical transition and gender confirmation process—to include travestis and trans men in the health services offered.

2013: The Brazilian Institute of Transmasculinities (IBRAT) is founded, with the goal to defend the rights of and promote the quality of life of trans men, as well as transmasculine non-binary people.

2013: The Ministry of Health presented a comprehensive National Policy for Integral Health for Lesbians, Gays, Bisexuals, Travestis and Transsexuals.

2013: Keila Simpson became the first trans person to receive the Human Rights Award from the Presidency of the Republic, awarded by then President Dilma Rousseff.

2013: The Gender Identity Bill—known as the João W. Nery Bill—was filed by congressman Jean Wyllys. This law proposes that every person has the right to recognize their own gender identity, live their lives accordingly, and be treated and identified accordingly—in particular in regards to the usage of their names, pronouns, and other forms of identification. After several back and fourths in the Federal Congress, the bill was last archived in 2019.

2014: In November 2014, the Federal Council of Psychology initiated a campaign for de-pathologizing of travesti and trans identities, an action in which psychology professionals, researchers and researchers, activists, transgender and travestis were invited to join the debate.

2014: CNCD/LGBT published a joint resolution with the National Council for Criminal and Penitentiary Policy establishing new guidelines for the carceral treatment of the LGBT population in Brazil. The resolution determined that travestis and trans inmates have the right to be called by their social names, as well as to dress and fashion their hair according to their gender identity. It also acknowledges that travestis and gay men in male prisons are especially vulnerable, and that "specific living spaces should be offered” to guarantee their safety. According to the resolution, male and female transgender people should be sent to female prison units. The state should also ensure equal treatment for trans and cis women in jail.

2014: The National Forum of Black and Black Travestis and Transsexuals (FONATRANS) is founded.

2014: Enem, the National High School Exam, allowed candidates to use their social name. This became an important tool for helping trans people and travestis access higher education. From this moment onwards, other actions started to emerge, such as affirmative policies and quota reservations for trans people in universities.

2014: The first Trans March in São Paulo was held during the IV Southeast Meeting of Travestis and Transsexuals.

2015: The First National Meeting of Trans Men took place at University of São Paulo.

2015: A case on transgender access to toilets began to be judged by the Brazilian Supreme Court (STF). The lawsuit came to the Supreme Court through the hands of Ama Santos Fialho, a transgender woman who in 2008 was forcibly removed by security guards from the women’s bathroom of a mall in Florianópolis.

2015: The Mayor of São Paulo, Fernando Haddad, launched Transcidadania (“Transcitizenship”), a program that promotes the social reintegration of travestis and trans people in vulnerable situations. Beneficiaries are given a two-year grant to complete their studies, take vocational courses, while also receiving medical, psychological, pedagogical, and legal support. In 2019, after four years of processing and political struggle, Transcidadania was ratified by law as a policy for the city of São Paulo.

2016: Dilma Rouseff, then president, by decree, asserted the right to a social name and the recognition of trans people’s gender identity in the federal public sphere. Federal agencies and entities must adopt the social name of the travesti or trans person. Pejorative and discriminatory expressions are forbidden to refer to travestis or trans people.

2017: After 25 years of activity, the ABGLT—the Brazilian Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Travesti, Transgender and Intersex Association—elected its first trans president, Symmy Larrat. Born in Belém do Pará, Larrat is the first trans person to be general coordinator for the Promotion of LGBT Rights of the Human Rights Secretariat of the Presidency of the Republic during the government of then president Dilma Rousseff. Larrat also coordinated the Trans Cidadania program, under Fernando Haddad, which was the largest program in Latin America specifically for travestis and trans people.

2018: Seeking to foster respect, and minimize violence and school dropout rate due to bullying, harassment, embarrassment, and prejudice, the Ministry of Education authorized travestis and trans people to use their social names in school records.

2018: The Federal Council of Psychology published a resolution that guides psychology professionals to de-pathologize travestism and transgenderism in order to contribute to the elimination of anti-trans hatred and discrimination. Since then, the Federal Council of Psychology has been persecuted by religious, fundamentalist, and conservative groups.

2018: The Federal Supreme Court (STF) allowed for the change of name and gender in the civil registry to be done by self-determination alone, and directly at the civil registry offices without the need of gender reassignment procedures, or medical reports or diagnoses.

2018: The Legislative Assembly of the state of São Paulo elected Erica Malunguinho, the first trans woman to be state representative. That same year, Robeyoncé Lima and Erika Hilton were both elected co-state representatives, respectively for the states of Pernambuco and São Paulo, through collective candidacies. In a collective candidacy, members of the same party mobilize to obtain votes together. If the main representative is elected, the entire group will have unofficial participation in the political discussions and debates that permeate the chamber.

2019: President Jair Bolsonaro extinguished the National Council to Combat Discrimination and Promote the Rights of Lesbians, Gays, Bisexuals, Travestis, and Transsexuals (CNCD/LGBT), a huge stepback for the movement

2019: By eight votes to three, the Federal Supreme Court recognized “LGBTphobia” as a crime of racism. With this decision, anti-homo/bisexual and anti-trans discrimination became a crime subject to 1-3 years of imprisonment, in addition to a fine.

2020: The Federal Council of Medicine updated its resolution concerning access to care for the trans and travesti community, addressing issues such as puberty blockers, which are still considered experimental. It also established better safety procedures for hormone replacement therapy and gender confirming surgeries.

2020: The Supreme Court ended restrictions on blood donations by LGBTQI+ people. Until the beginning of May 2020, blood centers were forbidden from collecting blood from men who had had sex with other men 12 months prior to their donation. This restriction applied to the whole LGBTQI+ population. However, on May 8 of this year, the Federal Supreme Court (STF) lifted the restriction, considering the measure unconstitutional and discriminatory. In addition to being a victory for the LGBTQIA+ population’s struggles, the STF’s decision comes at an important moment. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, blood centers are low on blood supplies—and solidarity is welcomed with open arms.

2020: In the nation-wide municipal elections of 2020, from the 294 travestis and trans candidates running, 27 were elected, representing an increase of 237% compared to 2016. Of those elected, 35% are Black or PoC, 16 are affiliated to left-wing parties, eight to center parties, and two belong to parties on the right, being one trans man and the remaining travestis and trans women. Seven candidates received the most votes in their respective cities: Linda Brasil in Aracajú (SE), Dandara in Patrocínio Paulista (SP), Tieta Melo in São Joaquim da Barra (SP), Lorim de Valéria in Pontal (SP), Duda Salabert in Belo Horizonte (MG), Titia Chiba in Pompeu (MG) and Paullete Blue in Bom Repouso (MG). This election also saw the first intersex person being elected in the country.

This is an ongoing project. If you have any corrections or items to add to this timeline, please contact us at mail@futuress.org.

Bruna Benevides (she/her) is a Brazilian LGBTQIA+ activist. Originally from Céara, and currently based in Rio de Janeiro, Bruna is the first transwoman active in the Brazilian navy, where she holds the position of Second Sargent. She’s also the secretary of political articulation at ANTRA, and a member of ABLGT.

The title of this vertical, Epistemic Activism, is an homage to the disabled, nonbinary Iranian/SWANA designer and researcher Aimi Hamraie. In their book Building Access: Universal Design and the Politics of Disability, epistemic activism is described as a form of

political action that occurs within academic fields to shape social norms and practices.