Moving fast and slow.

Assumptions about a normative kind of tempo are bolted into capitalist values of when and how it is right to do something. A ceiling fan is assumed to spin rapidly, so as to create a breeze. What happens when it doesn’t? My bodymind is expected to move quickly, to keep up with turbo capitalist computational clock time that counts to the millisecond. I’m expected to know what I want, speak it out, deliver it with confidence now. What happens when I don’t—or can’t?

In early 2023, during my visit to the exhibition Generalización at the contemporary art museum Tamayo in Mexico City, Mexico, Tania Pérez Córdova’s installation 10 Minute Spin, 2014/2022 looped my attention into its spin. As the wall label stated, the work is inspired by the figure of the metronome: “the device used to maintain a rhythm in music, which can adapt to different tempos—the artist intervenes in an everyday object, a fan, to delay the time in which it spins. the artist intervenes in an everyday object, a fan, to delay the time in which it spins. Beyond canceling its function, Pérez Córdova considers this object as an intervention in space, which has the capacity to insert one value of time into another.”

This insertion of alternative time within an expected normative timeframe fascinates me. It is precisely one of the functions that I find most challenging—and structuring—about Access Riders. Access Riders are written documents used by artists and designers coming from disability communities to outline our access needs—to describe what we need to be fully in a space, whether online or on-site. These may include changes to practices such as snacks, break times, an understanding of what is a “normal” length of time to wait for an email response, and implementing physical or social transformations to the space. Access needs can change depending on fluctuations of someone’s hormonal cycle, a flare-up from a chronic illness, a personal trigger from past trauma, or even how well they slept the night before. Everyone has access needs, some of which are normalized—for instance, the practice of wearing glasses, or taking written notes to be able to better remember something. And there are the access needs that—as a result of unequal power relations—are not yet cared for. One of the things I find beautiful about access is that it is ever-changing. Nevertheless, some things can and should be normalized—and even legally and structurally implemented—so that processes of making spaces accessible are not the burden of disabled people and our friends or colleagues.

“Access is also a day-to-day thing. The process of finding out how to be together, and what might make it sufficiently possible and safe to be in any space for our bodyminds—this has to be continually figured out.”

Frankly, it is so energy-zapping and time-consuming to inquire about basic accommodations such as rest spaces, wheelchair accessibility, scent-free spaces, and gender-neutral bathrooms in institutional settings. Access Riders intervene in these spaces and contexts, necessitating the opening up of space. This, however, requires a different temporality when there are often not enough resources and not enough time. Simultaneously, access is also a day-to-day thing. The process of finding out how to be together, and what might make it sufficiently possible and safe to be in any space for our bodyminds—this has to be continually figured out. There is a necessary rigidity for many things—like installing permanent wheelchair ramps—and also a fluidity of many things—like providing the right food so no one has an allergic reaction. All of these point to the beautiful diversity of bodyminds that there always is around us, and that always informs ways of being together that are situated, specific, and real.

I love point 10 from artist Johanna Hedva’s Access Rider that points to the future-making aspect of these documents: “For the future—It would be so cool, and you’d make me and my friends and many others very happy, and you’d increase the attendance of your events by a lot, and you’d become a working part of building the kind of world that needs to be built if you would follow this document not just for me, but for all your work in the future.”

Access Riders communicate anyone’s needs in order to be in a space, show up better, and create more possibilities for anyone’s bodymind and community. They make space, tenderly care for, and promote thriving for anyone who uses them—and work on unmaking ableism.

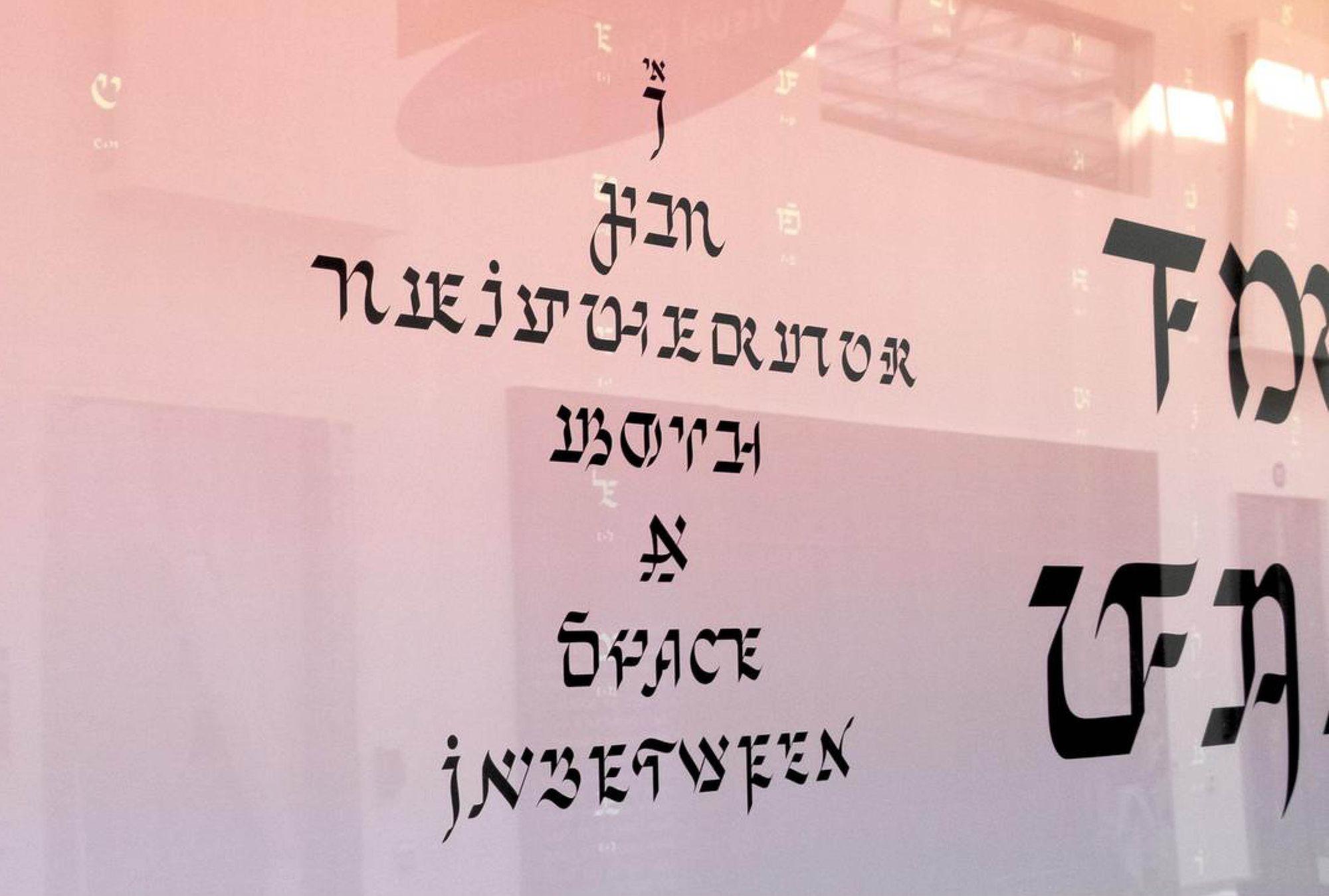

While part of ableism is to not discuss disability and ableist infrastructures, Access Riders create the possibility of naming values and access requirements, while simultaneously cutting down on communication labor and access-making-exhaustion in various work contexts. As curator and cultural organizer Taraneh Fazeli describes in the homonymous exhibition she curated, the value of time that Access Riders hold space for is “sick time, sleepy time, crip time.” Essentially, they demand care outside of what the cis-heteronormative normative family and work week can reliably render possible. Furthermore, Access Riders hold space open for trans* time (such as transition leave) and queer family time (like bringing your queer family member to advocate for you), both timelines that fall outside of chrononormative frameworks. As discussed by scholar Kadij Amin in his research on trans* temporalities, “chrononormative” refers to norms based on linear life stages, assuming that everyone desires and can participate in conventional family structures, own a house, have pets, and take yearly vacations. Making space for queer and trans* time might mean including on anyone’s Access Rider space for gender-neutral bathrooms and discussing the possibility of gender affirmation leave, should that become needed in the future.

To care for access takes time; to care for non-normative experience takes time; to make space where there has been no space because I, as a trans*masc neurodivergent person, need to ask for it—it always takes time. With all frameworks designed to regulate and exhaust our bodies and time, the possibility to incorporate time into any setting becomes crucial to avoid burnout in cultural work. This value, which I insert into spaces, enables making different movements possible that otherwise would be rendered out of time.

In my daily studio practice as an artist-designer, I move both fast and slow. Fast: I save time and energy by ordering materials to be delivered, and I make time for my body by insisting: “No—I need there to be a break in the meeting.” And then there’s the slow: I fall ill (my body crumbling in response to a new medicine with problematic side effects), or I don’t know how I am feeling/thinking about a new concept—I need time, and the s-e-c-o-n-d-s stretch on.

At institutions that I collaborate with, often there isn’t enough time. Recently, there was a budget allocated for Sign Language interpretation at an event in which I participated. My collaborator, Iz Paehr, and I had requested this interpretation since no one had thought of it before, and still, when the time for the event came, it wasn’t cared for. There had not been enough time to plan for it or to contact someone to ensure they could be there. There was no time.

“Due to the precarious funding nature of their work, many art institutions often don’t decide to make the time to think along with accessibility practices.”

Another experience of being out of time: some years ago, I was invited to participate in an event named “Collective Conditions” hosted by my friends and colleagues from the feminist tech collective Constant in Brussels, Belgium. When asking them if there was an elevator in the space, they responded: “No.” I then asked: “How can the conditions be collective if they automatically exclude many bodyminds from the very start?” Over the course of writing this article, I have learned that they are making the time. As their focus for 2024, Constant is spending time caring for disability accessibility by centering practices of accessibility and unmaking ableism. Still, generally, due to the precarious funding nature of their work, many art institutions often don’t decide to make the time to think along with accessibility practices. How can there be structural time made for access practices at institutions of all scales?

More context, more possibility. In Black feminist Lola Olufemi’s brilliant book, Experiments in Imagining Otherwise, she notes possibilities of “the future that we prefigure via modes of rehearsal.” Every time I send my Access Rider to a new institution or collaborator, I rehearse a way of being in space that humanizes my needs moving in a field that, at worst, tokenizes my experience and, at best, meets and enriches it. This rehearsal, like all rehearsals, goes better sometimes and worse at other times. I’ve been in contexts where the needs of my Access Rider are met—there are regular snacks, breaks, spaces to rest, and discussions around communication norms—and as an outcome of these needs being met for me, the space that is created is more accessible for myself and my fellow disabled community. Ideally, the considerations I introduce into the space stimulate conversations amongst staff, colleagues, and policymakers, leading to the development of new practices.

At other times, I’ve been in contexts where the needs of my Access Rider have been met, however, the difficulty and trouble of the labor to make this access possible were levied upon me. Time and time again, I’m reminded how much “work” it was to make this access possible, not once considering how this is a structural issue due to ableism—a structural privileging of non-disabled people over disabled people that is far-reaching, structural, pervasive, and oftentimes so entrenched it goes unnoticed. It is an ableist notion that I should be grateful that minimal access practices have been made.

Furthermore, I’ve been in places where, even though the points on my Access Rider have perhaps been acknowledged, I then arrived at an event/context—online or in person—and none of the measures have been taken. It places an enormous drain on my energy and my capacity to respond, improvise, and perform in any space. If I mention this then, or later, it has happened that my feedback is rendered as a complaint—I am understood to be “ungrateful” and then not invited back for further work. These experiences with making access underscore the crucial work of feminist writer and scholar Sara Ahmed, who continues to articulate and make space for the recognition of care labor that access requests can be understood as. In her book Complaint!, she writes, “We need to remember that a complaint is a record of what happens to a person, as well as of what happens in institutions. Complaints are personal as well as institutional. The personal is institutional.”

“Access Riders point out needs that are hard to discuss in a world that centers ableism and renders everyday experiences of moving through the world potentially difficult.”

In the case of Access Riders, the personal becomes institutional, following Ahmed, as access needs are shared and then shape the conditions of any collaboration. When I speak about what I need in any space, I not only make myself vulnerable to those needs not being met. Moreover, I am also opening myself up to creating conditions that would actually be feasible to complete/perform any work and do it well. At the same time, I am aware that what I might need is often not yet standard practice in any institution. Therefore, when anyone’s needs are gingerly shared in an Access Rider, and then dismissed, these institutions are prone to racism, ableism, anti-queer sentiment, and other exclusive and oppressive behavior due to this lack of attention and lack of attending to what has been shared. Access Riders point out needs that are hard to discuss in a world that centers ableism and renders everyday experiences of moving through the world potentially difficult. By raising access needs and sharing Access Riders, these documents promote a culture of dismantling ableism by openly sharing experiences.

Time to care for access is time shared to enact how spaces can be different. By inserting a time for care, time for access, time for non-normativity, and time for our bodies back into whichever sites of work we move in together, Access Riders insert time for us to be here, shaping collective experience.

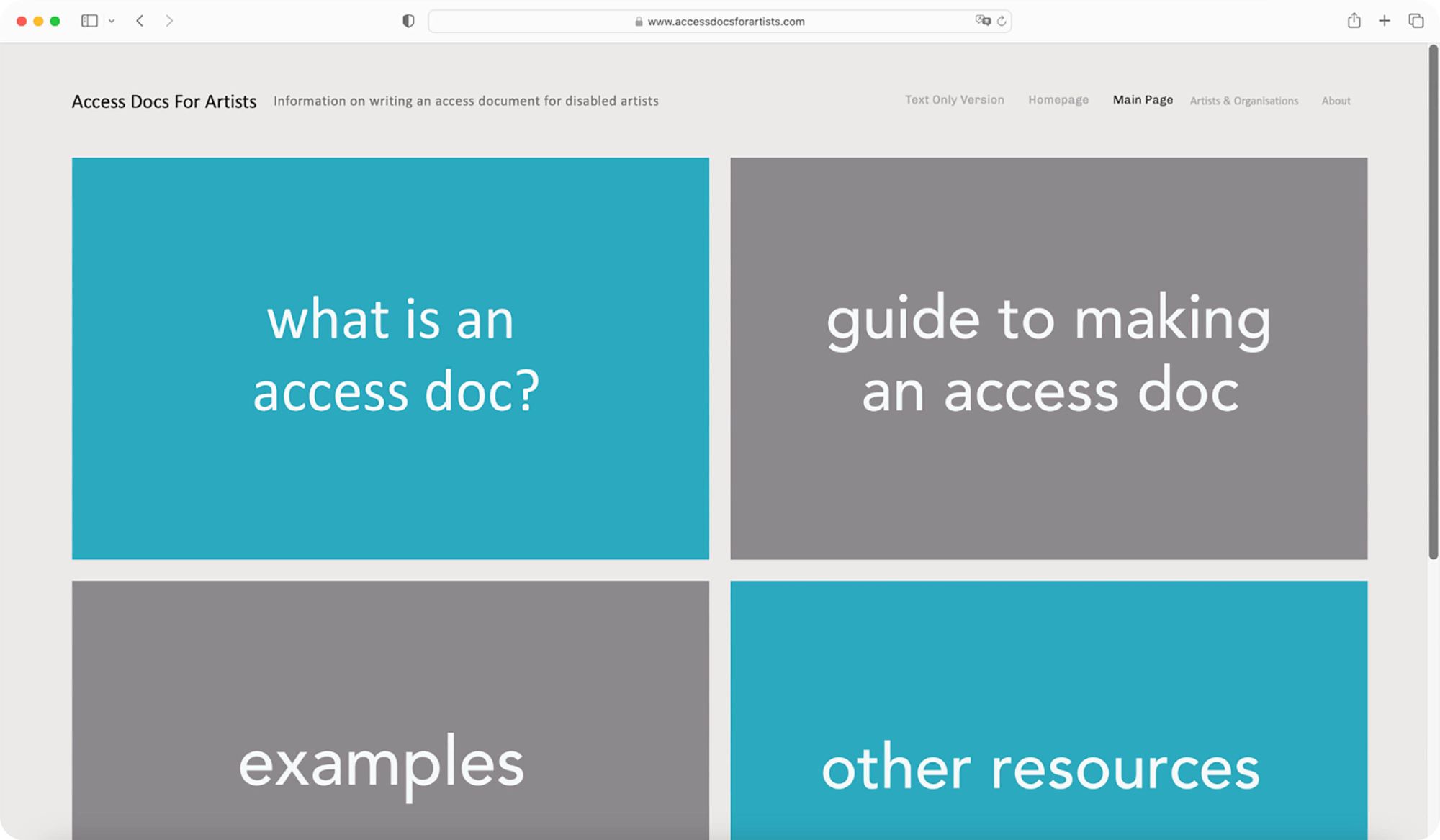

To make your own Access Rider, check out https://www.accessdocsforartists.com/homepage created by Leah Clements, Alice Hattrick and Lizzy Rose.

Ren Loren Britton (they/them) is an artist/designer tuning with practices of Critical Pedagogy, Trans*FeministTechnoScience, and Disability Justice. Their research plays with queer proliferations of otherwises, they practice joyful accountability to matters of anti-racism, collaboration, Black Feminisms, instability, Trans*Feminisms, and transformation. With Iz Paehr as MELT, they study and experiment with shape-shifting processes as they meet technologies, sensory media, and pedagogies in a warming world (Meltionary). Britton is currently a fellow with their project Counting Feelings with medienwerk.nrw + Department of Art & Art Theory at the University of Cologne as well as a fellow with the design department of the Sandberg Instituut, Amsterdam, NL.

Title image by Ren Loren Britton.