It’s late December in London, and it’s freezing outside. Our cold limbs find some solace in the warmth of the indoor space, while we turn on our computers and get ready for a long night of brainless work on Adobe Illustrator. As it gets darker outside, we fill the room with the clacking sounds of the keyboards and conversations ranging from love to politics, feminism to music, and decoloniality to food. Because of our shared background in architecture, we can get lost in analyzing how it always all comes down to space. This is how it has been between us since we met and our minds instantly clicked: two women who grew up at the opposite sides of the globe, yet found synergy focusing on similarities rather than differences.

The holidays are getting closer, and nostalgia hits us in waves. The cities shaping our conversations are our distant homes that we miss and crave.

“In Bologna during this time of the year, the sharp cold makes the air smell like roasted chestnuts.”

“In Rio, the temperature is so high that all you want is to be submerged in any body of water.”

As the hours pass by, these two cities take shape through detailed descriptions of situations, encounters, traditional and modern customs, feelings and temperatures.

“Tell me about New Year’s Eve in Rio, I’ve heard it’s really something!”

And the story begins.

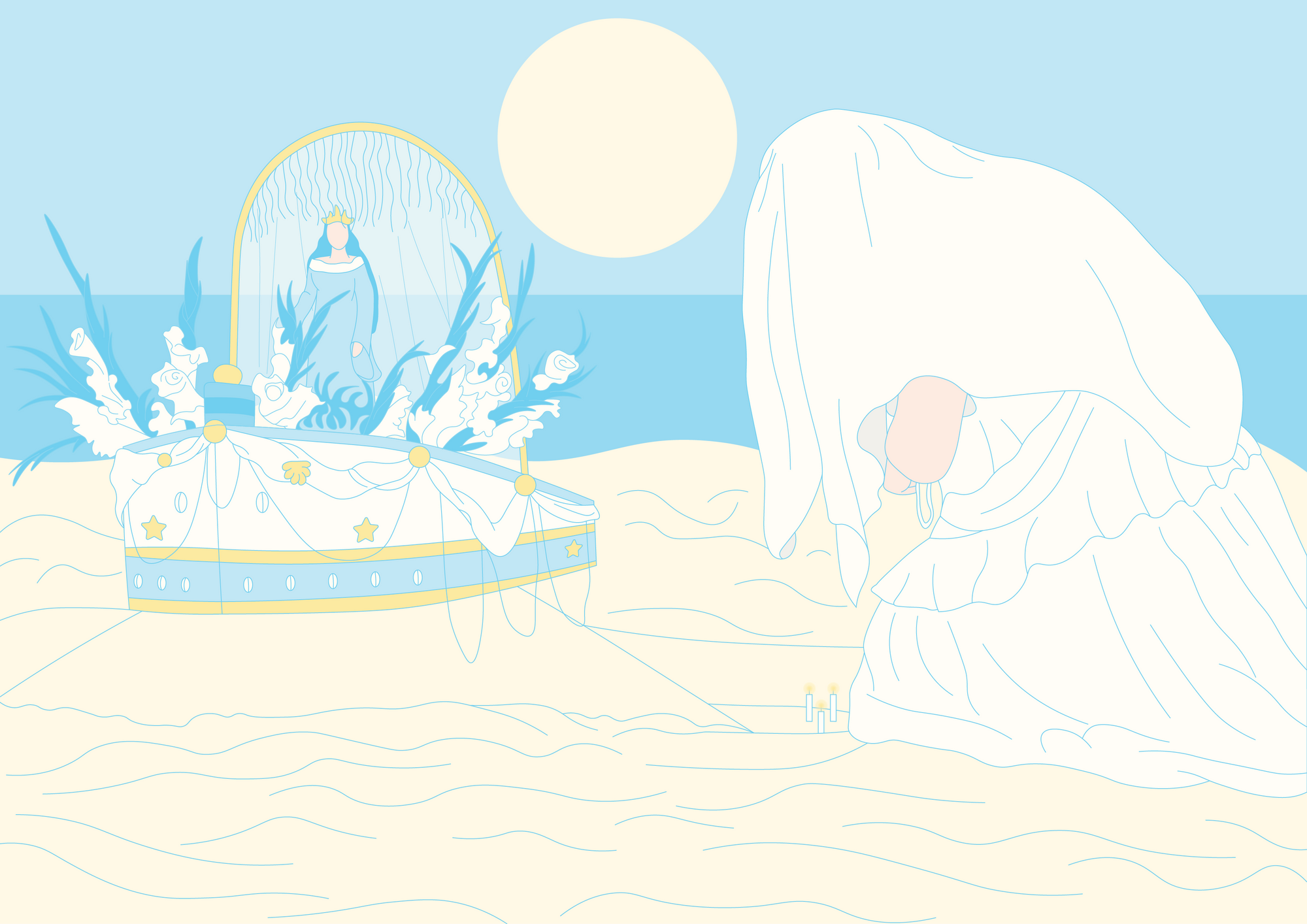

“Everybody else is at the beach. This is how it should be. Midnight is approaching, and the water’s gentle murmur follows your eyes, which attentively behold the sky about to be filled with the New Year’s Eve fireworks. You soon notice that there is no one quiet around you; there is a constant transit of people coming and going towards the sea. No one wants to miss jumping the first seven waves of the year to wish for luck, peace, and love. Once you finally find a spot to sit, breathe, and avoid the crowd, the moon and the candle lights show that everyone wears white.

“Perhaps you’re experiencing encantamento, a sensation that takes you out of the present time and space, while you become one with the plurality and material reality of nature.”

People bring offerings to the water—this shows their gratitude for the cycle that is ending, while asking for good fortune for the one ahead. Some offer flowers and champagne to the sea, while others let the currents take away tiny wooden boats, where a reproduction of the Virgin Mary is placed alongside flowers, fruits, mirrors, perfumes and shells—“Our Lady” and her gifts are floating. You feel the summer breeze of the festive dawn and feel a presence; a cool shiver at the back of your neck. Perhaps you’re experiencing encantamento, a sensation that takes you out of the present time and space, while you become one with the plurality and material reality of nature. Luiz Antonio Simas and Luiz Rufino described it in their 2020 book Encantamento: sobre política de vida as “a drive that tears the human being apart to transform it into an animal, the wind, a water body, a river rock and a grain of sand. [An embodiment that] pluralizes the being, decentralizes it to showcase that it will never be total, but ecological and unfinished.” With such a reaction to the energy surrounding you, you might even forget that New Year’s Eve is an unusual day to worship the Mother of Jesus. “Maybe you do not even realize the strangeness of praising the Mother of Mercy by dancing and offering her alcohol and cigarettes…”

“I have the feeling that you’re trying to tell me something.”

(Chuckles) “The image of the Virgin Mary is actually a representation of a Yorubá Orisha who, in Brazil, is called Yemanjá, meaning the Great Mother of the Sea. She is a divine character praised by my religion, the Umbanda, alongside many other African-rooted religions, cultures and places. Hey, look! It’s snowing!”

Our eyes gaze at the landscape outside the window, while a white soft blanket gently builds up on top of buildings, crossroads and sidewalks. Knowing that the next morning, it will soon turn into a slippery layer of dirt, slowing down traffic and pedestrians rushing somewhere through London’s busy life, we contemplate the image. Yet, our imagination is somewhere else—warmer, distant. “Não sou eu quem me navega, quem me navega é o mar, é ele quem me carrega como nem fosse levar…” A mystic sparkle is tangibly changing the energy in the air, and whilst our bodies are still, our minds are travelling West, crossing the Ocean through endless rhythmic circles of seven waves.

Navigating other horizons, meeting Yemanjá

To understand Yemanjá, it is important to know that, in Brazil, She is praised in a series of African hybridized diasporic religious forms. The interweaving of cultures that form these religions is tied to Portuguese colonial history and all the diverse diasporic cultures of West and Central Africa nations (mainly the Yoruba, the Bantu and the Fon) which were forcibly relocated to Brazil during the colonial era; and finally, to numerous Indigenous populations expressing the ancestrality of the land (such as the Tupiniquins, the Tupinambás, the Guaranis, the Pataxós and the Karajás). The Orisha Yemajá is thus known, praised and physically present across the whole Brazilian territory in the form of statues, images, and other representations, with devotees from a wide and diverse range of religious manifestations such as Candomblé, Jurema, Cabula, Catimbó, Quimbanda, and Encantaria, among others. One of the most knowledgeable of these cultos [a Portuguese term used as a synonym of “religious practice”] is Umbanda, which was institutionalized by the government during the Estado Novo period (1930-1945; remembered now for its strong nationalist state project) as the first Brazilian religion.

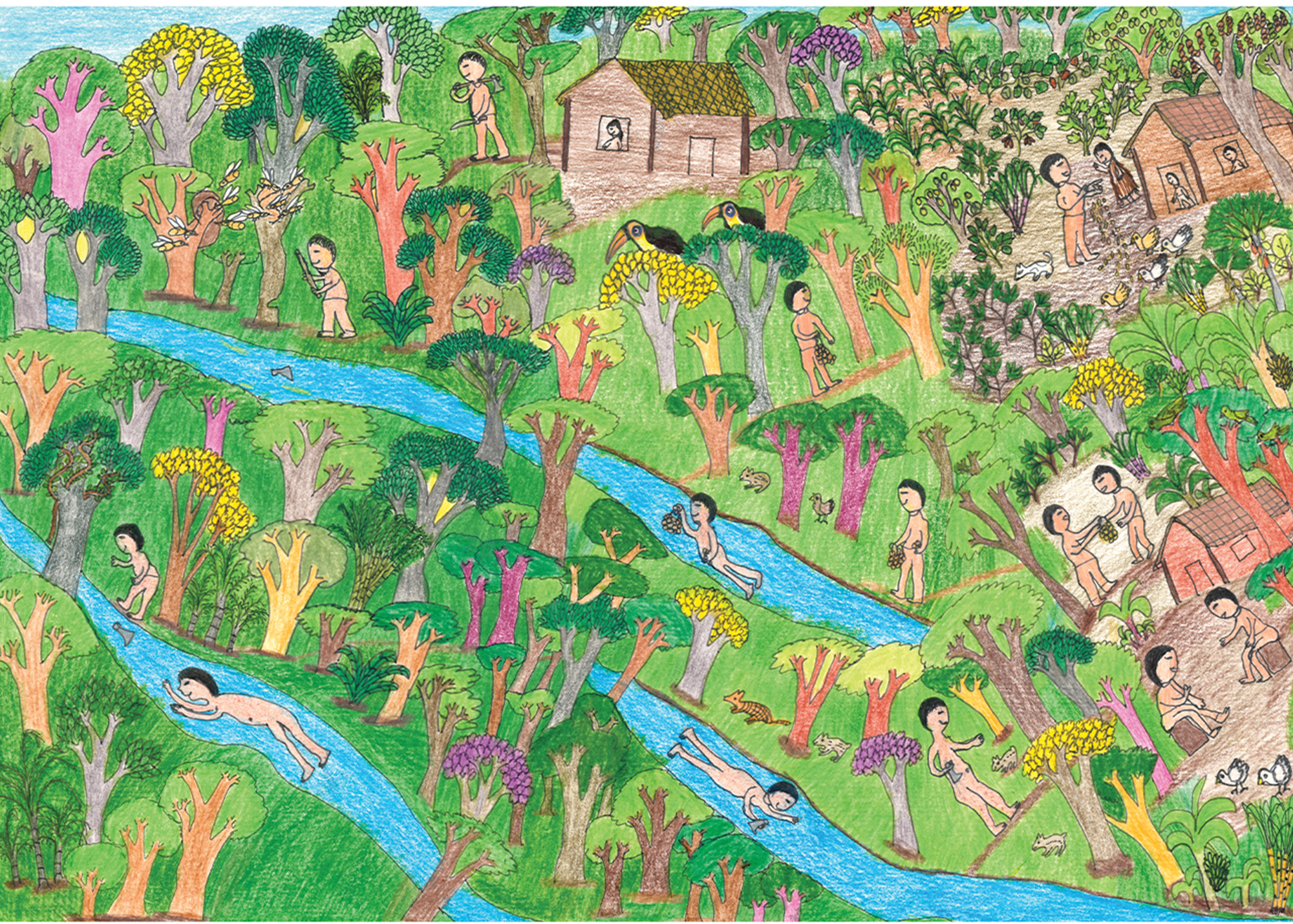

Umbanda’s doctrine is built upon a process of syncretism, at the crossroads of elements of the Yoruba Orishas and the Bantu Nkisi belief systems, Brazilian Indigenous healing and spiritual practices, together with European spiritualism and Christianity. Its roots are still uncertain due to the systemic repression of these knowledges after four centuries of enslavement and at least five centuries of persecution and erasure. Yet Umbanda is continually referenced as a matriz africana religion [Brazilian term for religious beliefs and practices rooted in different African cultures, including their often hybridized diasporic forms] because of the popularization and acknowledgement of the worship of Orishas as one of their main structural elements. Here, apart from the enforced process of Christianization and enslavement, the cultos de matriz africana started mixing with the Indigenous ones due to structural elements of resemblance. In fact, both traditions are usually tied to the concept of a perception of the cosmos that is embedded into ancestral knowledge and founded by principles of interdependence between humans and nature, promoting respect and acceptance for others.

Several Bantu communities were nomadic, and while moving from place to place they would always carry the memory of their ancestrality. Yet they would only praise their own divinities after reverencing the ancestors of the owners of new lands they travelled through. In this process, depending on how these other ancestralities would resonate with theirs, these could be incorporated as part of their own group of divinities, and be praised and respected as such. In Brazil, the Tupiniquins had a similar process of acceptance and incorporation of other beliefs, which became one of the remarkable traits of these populations that was essential to the process of cultural exchanges called brasilidade, conceptualized by Professor Adriano Pereira Jardim as a construction of Brazilian identity found at the crossroads of African diasporic memories and Tupiniquim indigenous practices.

“Unlike the idealized and constrictive image of the Virgin Mary, Yemanjá’s power is not reduced to an idealized conceptualization of motherhood. She has qualities but also flaws, and rational and irrational behaviors.”

Coming back to Yemanjá, it is important to highlight that She is one of the most worshipped Orishas in most of the Brazilian matriz africana religions. In Umbanda, She is the head of a number of falanges [spiritual arrangements guided by specific natural elements], reigning over all the sea’s elements. In Candomblé, She is known as the Great Mother of all Orís [Yoruba word meaning “head”, the part of the human body that is appreciated as the main connection between materiality and the divine]. In the Yoruba narratives, she represents one of the creators of the universe and is also recognized the responsible for women being accepted as oracle readers, a power that only men could carry before. Other Itans [Yoruba Orishas’ stories] indicate that She, at times, was also merciless with humankind, being mad at their attitudes towards nature, and She was even unfaithful to her partner Ogun—who She cheated on in an attempt to escape their toxic relationship. In other words, Yemanjá epitomizes femininity through its struggles and strengths, across metaphorical and mythological images of what that could mean. But, unlike the idealized and constrictive image of the Virgin Mary, Yemanjá’s power is not reduced to an idealized conceptualization of motherhood. She has qualities but also flaws, and rational and irrational behaviors. She performs Her role into the array of divinities as a female entity, representing womanhood through emotions and care.

“She is basically an honest representation of what the experience of being a woman feels like. But then… why does she look like the Virgin Mary?”

While the night goes by and the moon camly walks her natural circle, our conversation follows the rhythm of questions whose answers are hidden around cultural corners, and at the bottom of messy drawers filled with centuries of transnational political histories. This specific one is to be found in the box that resides forgotten in the basement, the one with a label saying “Brazilian extended colonial project.” Outside, there is the clanking churn of the garbage collector’s truck as it obliterates our waste, a stroke of irony that echoes our present search as we start unpacking this history.

Coloniality, syncretism and the myth of the 3 races

Any culto with a resemblance to African elements was forbidden by law from 1824, remaining so even after the liberation of the enslaved population in 1888, until the Estado Novo period (1930-1945). Afterward, though legally allowed, cultos de matriz africana have been constantly repressed and seldomly accepted in public spaces. During this whole period of repression, matriz africana religions’ devotees found a way to keep worshipping their deities and keeping their ancestral beliefs practice alive—by replacing their original representation with that of Christian figures. In the case of Orishas, Ogun became Saint George; Oxossi, Saint Sebastian; Iansan, Saint Barbara, and Yemanjá were camouflaged under the image of the Virgin Mary. It was a survival strategy, yet it entered the history books under the name of “syncretism.”

“Yet, can we call ‘syncretism’ a process that eventually led to only the representation of one religion to take over the others?”

The process of syncretism inherently followed a politics of marginalization, racism and discrimination reflected in the national myth of the three races—the white, the Black and the Indigenous—aiming to create a “purely miscigenated Brazilian identity.” Such an agenda relied on miscegenation as an eugenic national policy, reinforced during the Estado Novo, underlying the project of whitening the Brazilian population.

There is a widely dispersed narrative saying that Umbanda was created within that context, which served as a means to officialize the religion as the first purely Brazilian religion. According to this belief, Umbanda is a philanthropic, spiritual and esoteric practice with Kardecismo [a Brazilian designation of European Christian Spiritualism] roots—which facilitated its access among higher social classes and acceptance by the white population. Such discourse was definitely instrumental to the national eugenic project, which has been deeply problematic and violent.

“The replacement of the images comes alongside the erasure of [...] terminologies from their vocabulary, ultimately performing the colonial attempt to reach European Spiritism’s ‘purity.’”

The persistent reaffirmation of Umbanda as the only religion that was created in the national territory contributes to the simplification—and sometimes even erasure—of the multiple practices and hybridized diasporic forms of African religions spread across the country. In this context, syncretism genuinely serves as an instrument to re-colonize culture, spaces and bodies.

The consequences of coloniality and racism can still be found in our present times. This is made evident by the increasing number of white devotees in Umbanda, while other matriz africana and Indigenous traditional practices are being forgotten, and even forbidden in some places of worship. The terreiro—the traditional worship and community space resulting from a long process of resignification and transformation of the collective West-Central African diasporic memory in Brazil—is nowadays often called “a center,” and along with the loss of its name, it also loses its values. The replacement of the images comes alongside the erasure of Yoruba and Kikongo terminologies from their vocabulary, ultimately performing the colonial attempt to reach European Spiritism’s “purity.”

Interlude

It is getting pretty late, and our eyes are losing focus. As we move to the kitchen to make a cup of tea, we realize our bones feel cold and sleepy, while our minds are losing track of time when navigating through distant horizons. We silently sip and stare at the snowflakes cutting the dim halo of street lights, until “Eu não sou africano” by Candeia plays on shuffle on our computer’s playlis and the chatting sparks up again. As it happens in every good story, it is the right music at the right time...

“The song is sung by Candeia, Clementina de Jesus and Dona Ivone Lara, who were three of the most influential interpreters and authors of Black and marginalized music in Brazil’s national history. It was a protest against the introduction of the U.S.-American Black soul music on the national radio, which was seen as a threat to Brazilian samba. The chorus ‘I am not an African, nor a Northern American/ Under the viola and the pandeiro’s melody/ I am even more (or prefer) the Brazilian samba’ reflects the embodiment of the Brazilian identity whilst, at least apparently, denying their African ancestrality—passing a message of acceptance of this imposed national identity. Being Brazilian therefore means the recreation of certain histories from scratch, being passionately attached to the new narrative to the point of being against new external influences, but at the same time smoothly encroaching elements of Black ancestrality in their expressions.”

The whitewashing movement and the popularisation of Yemanjá

Today in Brazil, Yemanjá is respected by many, and known by basically everyone as the white “Goddess” of the sea; the One whose image became an icon of Brazilian pop culture, present in public spaces all across the country, entering homes and hearts through soap operas and popular music. She is commodified through objects available in souvenir shops and turned into fashionable patterns for clothes. In Rio Vermelho, Bahia, a big party takes place every 2nd of February, to celebrate Her... Our Lady of Seafarers. Certainly, among all the Orishas, Yemanjá and her representation is the most renowned to the public eye.

Different names are attributed to Yemanjá as evidenced here: Dandalunda, Janaína, Marabô, Princesa de Aiocá. Inaê, Sereia, Mucunã, Maria, Dona Iemanjá. Most of these recognise the Orisha as a legit syncretic “Goddess” that is embedded with the Yoruba deity and Indigenous mythical figures.

“So what happened? Why did She become so popular and why has She achieved such a status as a holy white saint, and not as the interactive mixture of Yemọja (the Yoruba Orisha) and Janaina (the Tupi-Guarani Divinity of the Sea)?”

“The answers can be traced back through public archives and stories by those who remember, and others who already asked similar questions.”

At some point in the 1950s, a crucial yet under-looked event took place, which drastically changed the perception of Yemanjá and the Umbanda religion at large. On a summer day of 1955, a white woman called Dalla Paes Leme, an Umbanda devotee, went to the beach and came back claiming she had a vision of Saint Yemanjá. She allegedly saw the “Goddess” coming out of the sea, wearing a holy-light-blue tunic with straight black hair blown by the ocean breeze and white skin reflecting the sunlight. Dalla Paes Leme and her vision soon became famous.

In the following months, a committee for disclosing Yemanjá’s newly designed portrait across the national territory was created and presided by Ms. Paes Leme herself. A frame of the white Yemanjá started touring every city in Brazil, and national communication channels were activated to cover a procession that was by every means a strategic political movement of colonizing and whitening Umbanda in order to affirm its whitewashed Brazilian-ness.

To change the image of something implies the replacement of its inherent values for representations, and this always follows a certain logic of power. Such power is being historically expressed not only in the reformulation of iconographies, but also as the domination of cultural practices through their erasure, simplification and/or commodification. Approximately two decades later, Yemanjá’s rites in Copacabana beach started to become a spectacle, drawing the attention of the Ministry of Tourism. Even under a Christian-nationalist military dictatorship government (1964-1985), the rites in her honor were not only allowed but actually encouraged in public spaces, and well-publicized in the mainstream media. Although still in a tone of otherness, the white image of Yemanjá has allowed a strange narrative of syncretism to permeate the Brazilian imagination, promoting the legal occupation of the public realm with figures and rites that were not necessarily Christian.

Today Yemanjá is the “Brazilian Saint,” representing a country’s history and its colonial agenda, manifesting as the eugenics project of whitening the Brazilian population. Her new image has been mutating through the years, increasingly resembling the Virgin Mary figure. As a result, Yemanjá is now dressed in the blue vests of Our Lady and used as a token for re-colonizing spaces of worship and occupying the streets of Brazil as a symbol of the success of the eugenic politics practiced behind the myth of the three races.

“She is now Iemanjá, with the capital I, since the Portuguese language could not assume the Y as an official letter of their alphabet.”

Temporary epilogue

Many months after that winter evening, we are still talking about love and politics, feminism and music, decoloniality and food—but this time we’re being physically apart, as we’re in the midst of a global pandemic. The nostalgia is now expressed towards those moments we were together, two young women coming from warm geographies, coping and adjusting to harsh and sometimes unfriendly winters through daily affection and knowledge-sharing. Since that cold mystic night, the issue of spirituality has never left our conversations, giving us the opportunity to both explore our intimate selves and dig into the controversies of its ramification within Brazilian politics.

During this research journey, many people generously joined our path sharing stories, struggles and hopes. Even though this is a very localized topic—meaning that material produced in English was scarce—we were endowed to meet Umbanda researchers, activists and devotees who were essential to the pedagogical process of both positioning ourselves and understanding the collective reflection on the iconography of Yemanjá; from individuals realizing and verbalizing their discomfort; to spiritual leaders producing knowledge both on social networks and via academic papers. The aesthetics of Yemanjá has performed as the catalyst for conversations revolving around Brazilian history and contemporary politics, allowing us to draw connections between phenomena and instances that are buried under centuries of either subtle or evident racist mainstream propaganda which still take place nowadays.

“What made Yemanjá being a white woman so popular? And why not the Black Yemanjá? We need to contest the fairness of this process because it was not accidental; it was well calculated in order to support a very specific political project.” – Brazilian spiritual leader, activist and researcher Pai David

“Brazil is not ready to talk about colonialism,” said Pai David, a Brazilian spiritual leader, activist for the Black rights movement and researcher of the whitening politics of the Umbanda belief. We met him via Zoom, and as soon as the camera came on, we noticed a small statue of a black Virgin Mary behind his back. We pointed it out and he said, “You see, some of us are well aware that there is a problem of racism in our terreiros, but we are not many. What made Yemanjá being a white woman so popular? And why not the Black Yemanjá? We need to contest the fairness of this process because it was not accidental; it was well calculated in order to support a very specific political project. Who benefited from it, and who was deprived of their own history?”

As we try to put an end to this written piece, we realize that it is a temporary full stop. Because of the ongoing forms of activism working towards the unraveling and dismantling of such marginalizing cultural systems, we cannot envision it as a completed conversation. Our journey through Brazilian activism of the otherwise found in contemporary Umbanda terreiros stands as an example of what decolonizing epistemologies might look like, but also how power can reach and manifest across the intimate scale of the body to that of public spheres. All of that is an ongoing process that is starting to produce relevant outcomes in the built environment, with increasing discussions on the issues of coloniality and awareness on the importance of territorial and narrative disputes for the creation of a heritage of resistance—a living heritage built upon an ancestrality that was crossed by systemic violences, and a memory constructed in diaspora.

We wish to thank Pai David, Adriano Pereira Jardim and Ayana Moreira for their generosity in sharing their knowledge, perspectives and feelings with us.

Carlotta and Naiara are passionate urban designers with a background in architecture. They met while pursuing the MSc programme Building and Urban Design in Development at Bartlett's Development Planning Unit (UCL, UK). Here they built a great friendship and partnership through research collaborations. Although coming from the opposite sides of the world (Naiara is from Brazil and Carlotta is from Italy), they found a special synergy in their approach to the world and design, driven by their shared decolonial and intersectional feminist principles. Right now, they are in the process of forming their own studio to bring their powers together and engage in an urban design practice aligned with these shared principles.

They have recently won the competition “Counter-territories: an international urban and art competition”, organized by Tajarrod Foundation, with a visual-research project on counter-mapping titled “The murderous border: Counter-trajectories in the context of Mediterranean migrations”. They also work together as co-founders and co-directors of the transdisciplinary design collective projektado.

Carlotta Trippa (she/her) is an Italian urban practitioner, researcher and activist, specialised and passioned about emotional geographies, feminist spatial design, participatory processes, and urban practices at the intersection of care and resistance. She has lived in Italy, France, Lebanon and the UK. She is now based in Bologna (Italy) where she works as an architect/urban designer on public, participatory and sustainable mobility urban projects. She recently ran for municipal elections with a municipalist political movement Civic Coalition and got elected as the head of the Environmental and Urban Committee within one of Bologna’s six Neighborhood Councils.

Naiara Yumiko (she/her)

is an activist practitioner with a strong interest in counter-cartographies and insurgent narratives. She works as a creative artworker for processes of co-design, strategic thinking and community engagement. Her special interests lean on participatory processes and the political role of communities over territorial struggles, having constantly engaged in practices that encompass critical analysis, community agency, the defense of anti-eviction movements and the fight for adequate conditions for social housing. She is an Umbanda practitioner and has a project called Mitologia de Umbanda to discuss graphically and textually the socio-historical process of marginalisation of her religious community through a decolonial perspective.

This text was produced as part of the Against the Grain workshop.