“Until the philosophy which holds one race superior and another inferior is finally and permanently discredited and abandoned, everywhere is war.”

—Haile Selassie I, Emperor of Ethiopia from 1930 to 1974

I first heard this quote in Bob Marley’s “War” (Island Records, 1976). Memories of it are closely linked to my childhood, growing up in the 90s in a Trinidadian ghetto. Morvant is a small marginalized village in Trinidad and Tobago, where many of my philosophy lessons were introduced through conscious reggae and calypso. This music, along with my grandmother’s teachings, instilled the value and importance of education as a tool to escape poverty—a lesson I still firmly believe.

Never in my wildest dreams as a child did I imagine that I would be studying in Switzerland at one of the largest art universities in Europe, Zurich University of the Arts (ZHdK). My main childhood goal—and also my grandmother’s—was for me to not become another statistic of teenage pregnancy, like my own mother and many other girls in my village. February 1, 2020, I moved from Trinidad to Switzerland. I left behind a desirable job as the lead designer at a pan-Caribbean financial institution, in order to pursue my Masters in Visual Communication Design. With my eyes firmly set on my project of creating a pattern textile design that represents the multicultural beauty and rich diversity of my Trinbagonian homeland, I was eager to embrace the next chapter of my life: education.

The beginning of my journey was off to a brilliant start, courtesy the global pandemic and lockdown. It was my first time living outside of my home country. My first time experiencing winter. The first time that I would be studying full time, while being unemployed. This was the worst time for all of these first times. There was no chance of making friends—I had barely met my classmates, before being confined to a small room and a small box on Zoom. I felt alone in this big, cold world.

During the global pandemic, even more African-American lives were lost. Breonna Taylor, Tony McDade, and George Floyd, among others, were murdered by the police in the United States. Summer came, bringing with it a wave of protest and solidarity with African Americans. With protests happening on almost every continent, it seemed as though the world was finally banding together to take a stance against police brutality, and working toward dismantling white supremacy, along with its engrained systems of oppression.

“I was in Europe, and now had full access to many of the cultural artefacts that I had only been exposed to prior via books and search engines.”

In the aftermath of attending the Zurich protest—the only place I had seen so many melanated hues in Switzerland—I was inspired to do some visual research for my master’s project, so I planned my visit to the nearest ethnographic museum. My expectations were high: I was in Europe, and now had full access to many of the cultural artefacts that I had only been exposed to prior via books and search engines. European art has always been central in my art education; art history was almost exclusively European, and as a graphic designer, many of my references for what constituted “good design” were also from Europe. I was ready and raring to go. This little Caribbean girl was in the center of the high art universe!

As I made my way through the hallowed halls, I selected my favourite playlist to set the mood: a mix of old school hip-hop, a couple of my favourite artistes, with a blend of underground rap. The anticipation turned into a mood that I couldn’t quite describe. The very idea of seeing art from India, the indigenous Americas, and African all in one place, with the same respect afforded to European art… the anticipation and the pride were bursting at my seams. Our greatness was finally being acknowledged... or as we say in Trinidad and Tobago, I felt like “‘We reach!” I met my classmates to go through the museum, but we eventually ventured into the exhibitions on our own, starting at our individual points of interest.

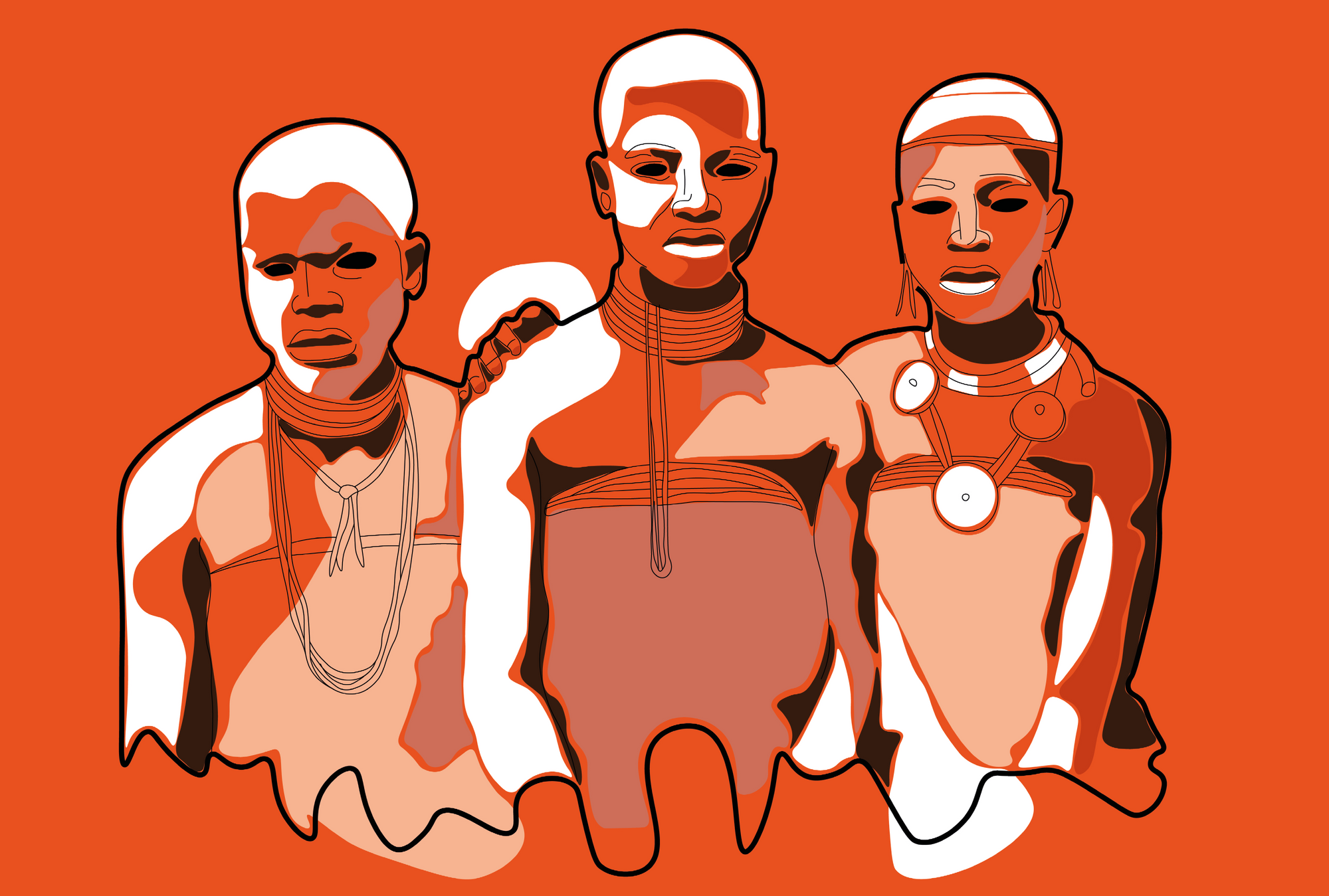

Eager to experience the art of my ancestors, I started at the African section. The first piece that captured my attention was a mask from Côte d’Ivoire. The mask held all the sculptural elegance of a marble piece, chipped away with the care and devotion of a skillful craftsman. It seemed to be inspired by nature, with touches of symbolism. It was fashioned after the head of an antelope, and embellished with fringe. Carved with precision, the horns were thick and strong, complementing the flat long curves of the ears, and creating a contrast to the hard, harsh edges of the jaw. At the center of the forehead a symbol was carved in relief. The finishing touches of the dual-toned fringe seemed to be dipped-dyed straw. Beneath it was the English inscription, three lines stating a name and description of the piece, and the location and time period of its origin. The German description included additional information of the material and the benefactor, who were bankers. The description was relegated to a maximum of three lines. That was it!

“Western societies have a difficult time understanding that rather than being objects, these artefacts are subjects.”

There was no context of how these pieces were used or their relation to the societies they were (are) from. There was nothing to hold these artworks to any high esteem. At that moment, I could feel my excitement start to wane. My music was fueling my sense of extreme disappointment while I continued through the exhibition. With every step weaving through aisles of artefacts, the rhythm of “Venom” by Eminem stoked the fire of indignation that was building. Even with my limited knowledge based on research into my African heritage, I recognized that some of the pieces were of religious significance. They possessed so much meaning to the culture and societies from which they were stolen. As I walked past more masks, totems, shields and vessels ranging in varying size and artistic detail, I came to the realization: they were not artefacts.

These are mementos of victories in battle.

These pieces belong to places of worship, places that would honour the ancestors that they embodied.

They are artistic representations of culture, accumulation of family and tribal history and memories of heritage.

They are more than vague, brief descriptions that provided no context.

Never before had I felt such affinity to a fictional character. The exasperated cognitive dissonance that I embodied led me to one conclusion: Erik Killmonger from Marvel’s Black Panther, was right: a wrong had been committed; a culture had been stolen from us, and trussed up as “artefact.”

“Yet what many Western museums and institutions wrongly and forcefully harbouring many so-called ‘objects’ from the non-West do not understand, or have not fully recognised, is that most of the so-called ‘objects’ have never been and will never be objects. The objectification of these ritual and spiritual beings, historical carriers, cultural entities, orientations and essences is in line with the dehumanisation and objectification of humans from the non-West.” In the article South Remembers: Those Who Are Dead Are Not Ever Gone, artist and curator Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung elaborates that Western societies have a difficult time understanding that rather than being objects, these artefacts are subjects. To understand their subjecthood, personhood and community—as they are considered in their original context and design—would require Western societies to take a new and “drastic shift in perspective and awareness of art, authorship and society.” This recognition would go against hundreds of years of artistic understanding and established curatorial practices.

“What the European ethnographic museums relegate to mere objects and artefacts indeed signify much more for the many societies that had their art, deities and historical subjects stolen.”

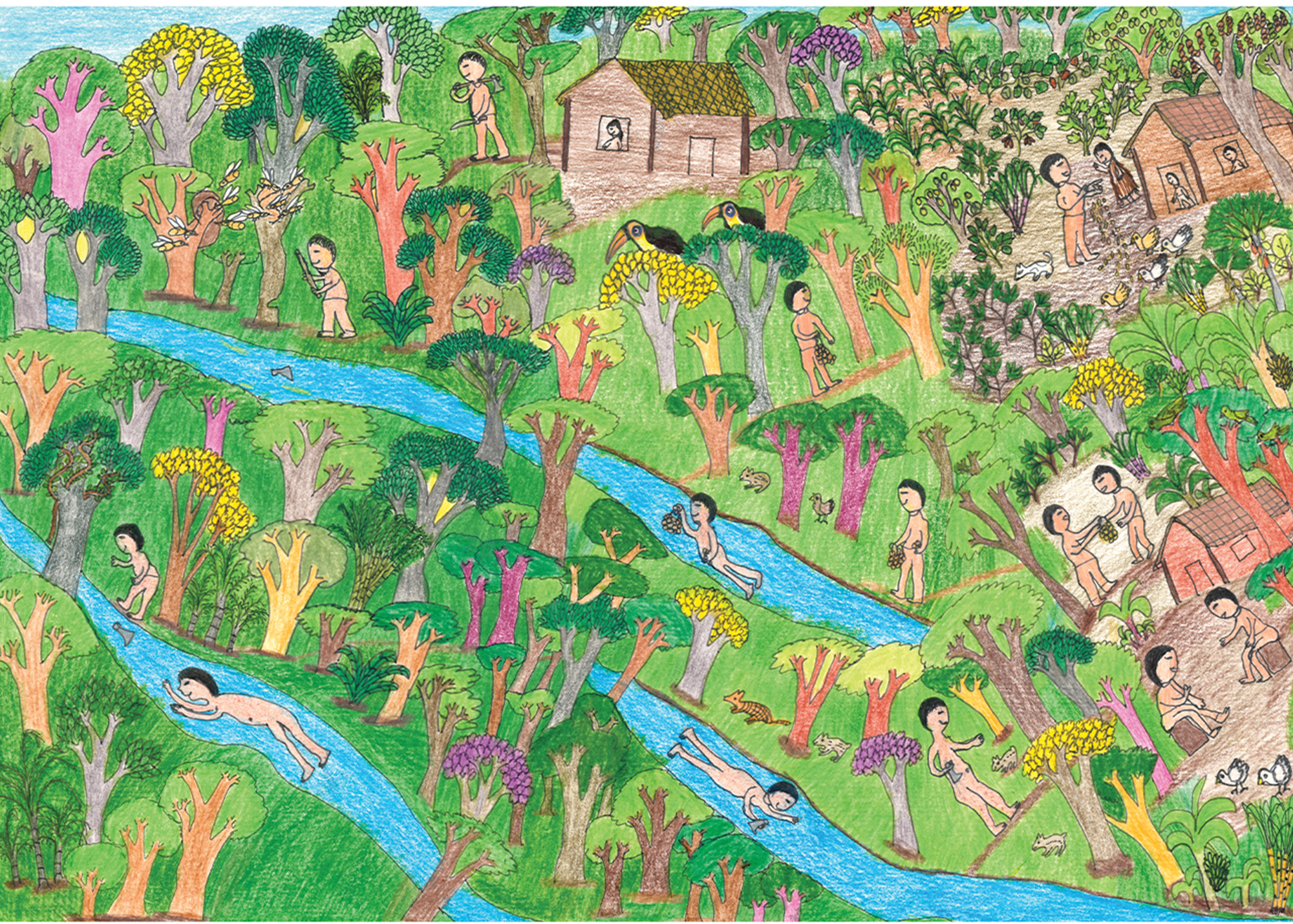

In Tlilli, Tlapalli: The Path of the Red and Black Ink, American scholar of Chicana cultural theory, feminist theory, and queer theory, Gloria Anzaldúa, points out that art making for mastery or the purpose of art is a Western construct. As art within indigenous cultures, the societies that were historically thought of (and taught to others) as “primitive” ascribes art as “aligning aesthetics with spiritual, functional and social contexts.” What the European ethnographic museums relegate to mere objects and artefacts indeed signify much more for the many societies that had their art, deities and historical subjects stolen. Furthermore, they also have great significance to the scattered diasporic societies who were also stolen and placed in the “new world,” and who still hold these pieces as representation of our own heritage, artistic prowess and interrupted histories. The true significance of “artefacts” specifically from Africa and indigenous cultures may never truly be appreciated or understood unless we consider the cultural implications of the greed, exploitation, and extermination that the Transatlantic slave trade had on African and indigenous societies.

“What would exist in ethnographic museums without the colonial stockpiling of ‘artefacts’? These museums now serve as displays of objectification and glorification of a bygone era where conquest, looting, pillaging and ‘discovery’ were trending.”

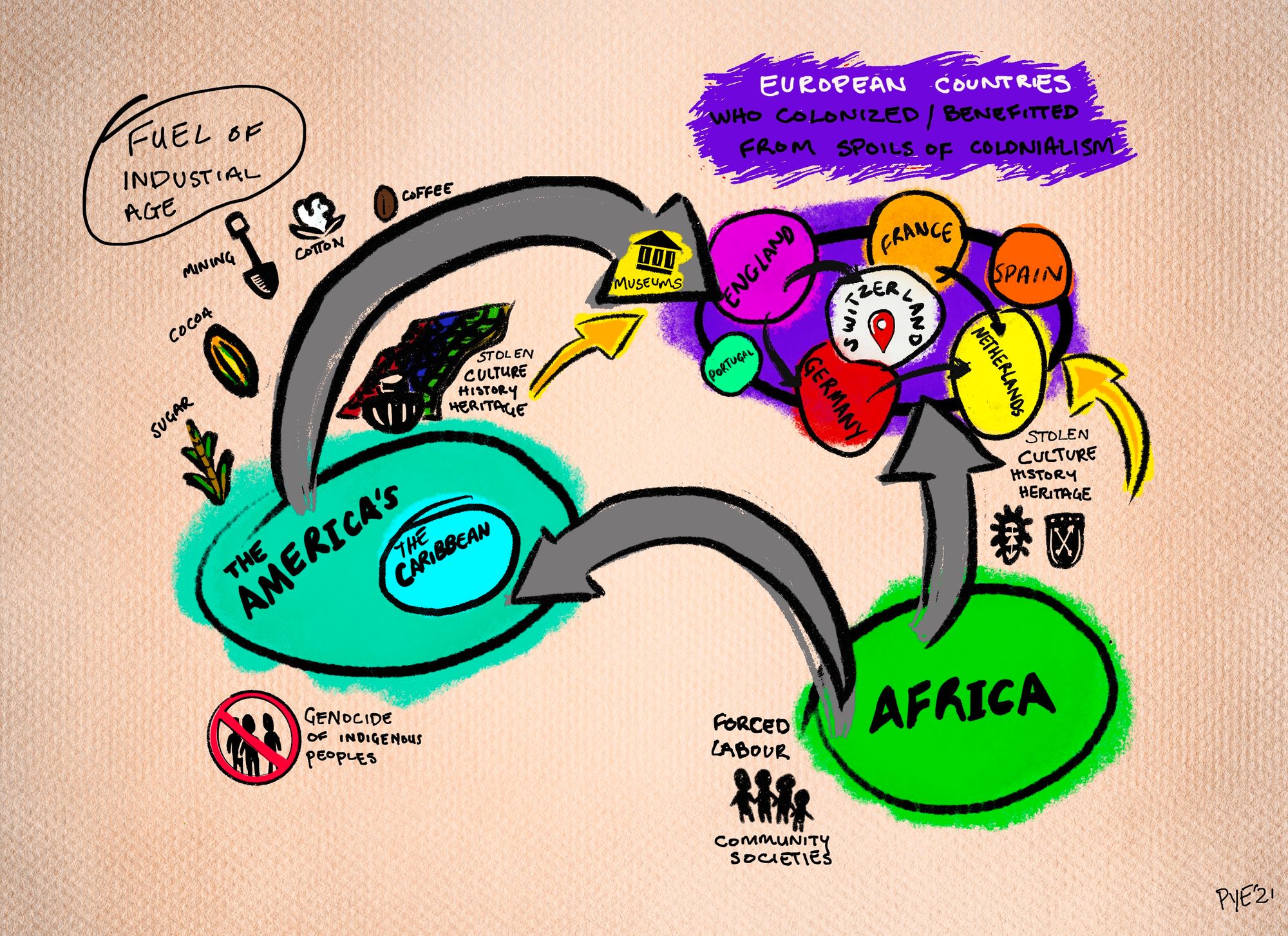

I am convinced that having a holistic comprehension of the context of culture of these subjects would provide ample reason to return them to their rightful places. But what would exist in ethnographic museums without the colonial stockpiling of “artefacts”? These museums now serve as displays of objectification and glorification of a bygone era where conquest, looting, pillaging and “discovery” were trending. They are the report cards of the atrocities committed against civilizations that were subjugated through the oppressive tool of the advancement of European societies: colonization. They underscore sheer disregard of human life in the genocides of indigenous peoples in the Americas, and the culling of African communities who would become enslaved peoples in the progression of Eurocentric modernity, Eurocentrism and ultimately Capitalism—or, as Peruvian sociologist, Anibal Quijano puts it, “the Coloniality of Power.” The creation of colonies in the Americas and the Caribbean (as they were all populated with many of the same indigenous tribes) have a direct relationship to ethnographic museums. The Caribbean at the height of the industrial revolution was the center of the new philosophical and economic order; the lab where international capitalism grew into the monster we despise today. According to Hilary Mc D. Beckles in his analysis of The Black Jacobins by C.L.R. James, and Capitalism and Slavery by Dr. Eric Williams, “It was also the place in which the ‘African resources’ were deployed in the genocide against indigenous Americans.”

Extrapolating the association between museums and the colonial project is not a new concept. Many have written about this correlation, but the relationship of both enterprises with the Caribbean region might be new to some. The conquest of the Americas meant millions of indigenous people died even before the forced servitude of Africans. Then, millions of Africans died before leaving the continent, after being kidnapped, and many were lost in the journey over the Atlantic. These civilisations were then bereft of their warriors, doctors, engineers, spiritual and educational scholars. Family structures were dismantled, homes destroyed, villages devastated, and places of worship were looted by slave raiders. Slave raiders plundered and pillaged “artefacts,” which were then sold to the colonizers, who now ascribed a new type of “value” to these items and displayed them in museums.

Museums in countries from the global north directly or indirectly benefited from or participated in the colonization of the Americas, which led to the devastation of African and indigenous Americans societies. Today’s ethnographic museums can be compared to colonial museums, which were made precisely to showcase the great power the European empire wielded to destroy and create societies in the name of “civilization,” and the spreading of modernity. What cannot be dismissed is the Caribbean’s role in the building of the wealth and accumulation of cultural capital in Europe. This goes beyond the disenfranchisement of not only the African continent, but many other societies that were also colonized. This is evident from the diversity within the Caribbean, which is also inclusive of a mélange of peoples from Asian ancestry.

“When some museums indicate that certain objects were given as gifts, one must remember that these were not gifts from African peoples, but from the German—or, (replace with your colonizer of choice)—adventurer, settlers or colonial administrators.”

As I made my way into other exhibits, my realization of the global colonial project as the foundation for the ethnographic museums treasure hoard turned into anguish. Not only did my African ancestors lose their heritage, but so did the other ancestors of many societies. I know that the provenance of some pieces are listed as “gifts,” but what are gifts when given under duress and coercion? When some museums indicate that certain objects were given as gifts, one must remember that these were not gifts from African peoples, but from the German—or, (replace with your colonizer of choice)—adventurer, settlers or colonial administrators. Certainly, no African peoples would readily give away any religious or ritual object to a foreigner, unless under considerable pressure to do so. The reputation of colonial administrators—whether British, German, French or Belgian—to readily resort to the use of force is well established. This sentiment can be added to many “gifts” from non-Western cultures that were obtained before and during colonial periods. Kwame Opoku beautifully highlights the many ways in which art from Benin was “stolen, sold or conned” from its rightful owners, and are now being held hostage at German ethnographic museums such as the Humboldt. It’s interesting to note that in summer 2020, the reconstruction of Humboldt Forum attracted a group of protestors called the Coalition of Cultural Workers Against the Humboldt Forum (CCWAH), whose cause is to bring awareness to the litany of issues around this institution, and its methods of cultural and financial extraction as it pertains to the denial of German colonial history. This incident brings to the foreground just how crucial the framing of colonial history is, and what it means for our modern museums. Again I’m haunted by the question: what would a European ethnographic museum look like without non-Western art?

Should we ask Killmonger—minus the murderous rage—to assist us in resolving this matter? So far, diplomacy or appeals by the countries to UNESCO to have their art returned have proven to be unfruitful.

By the time I left the exhibition, my initial excitement and pride had turned into a somber mood. It permeated my sleep at 3 a.m., not allowing me to rest, so I messaged my best friend to chat and help me unpack my feelings about this museum experience. There were many emotions to process—a wide spectrum of intensity, from awe and appreciation, to disgust and rage. Whilst these conflicting emotions marinated, my internal struggle reached an all-time high. I had learnt far more than I had bargained for. But this was not the education that I went to the museum for.

“I was in awe at the audacity of the colonial project to convince generations of people that their intangible culture was never good enough, while holding it hostage in places which are inaccessible to the actual owners of that culture.”

My thoughts went back to my childhood, and what I was taught about my culture and ancestry: African, East Indian and the Garifuna customs and beliefs were all reduced into “Devil Ting.” What we are taught to believe as “devil worship” was coincidently the culmination of the beauty displayed in these museums. It was not good for us to worship unknown gods, as they competed with dogma relative to the mission of civilizing the savages; yet it was good for colonizers to build “cultural capital.” The culture and climax of my complex Caribbean heritage was whittled down to being evil; a diverse mix of cultures and ethnicities, a result of centuries of enslavement and colonial subjugation—somehow, this was all just “evil,” but the act of colonial subjugation was not. The Europeans’ fear and ignorance of spirituality other than theirs was weaponized in attempts to eradicate belief and claims to ancestral and indigenous knowledge. For most of my life, I had embodied the colonial belief: that my culture was evil; meanwhile, I rejected and disregarded my grandparents’ indigenous knowledge and spirituality as superstition and Obeah.

“Wha sweet in goat mout’ sour in ’e bambam”

— Trinbagonian proverb.

What may be enjoyable at first, sometimes leaves a bitter aftertaste

I was in awe at the audacity of the colonial project to convince generations of people that their intangible culture was never good enough, while holding it hostage in places which are inaccessible to the actual owners of that culture. Through tourism, colonizers and those who hold non-Western “artefacts” gained during colonial time benefit directly from societies they have historically “othered.” Ethnographic museums are still a crucial part of cultural tourism, especially in Europe. The value and financial implications of ethnographic museums can be clearly linked to tourism, as Tudorache Petronela pointed out at a 2016 Economic and Finance Conference with a paper titled The Importance of the Intangible Cultural Heritage in the Economy. It stated that “this type of tourism is a vital source of income and employment, culture sustains development and heritage plays an important role in the creation of the character, identity and image of a city.” Imagine if this wealth of non-Western knowledge and tangible representation of culture, traditions and heritage are housed where they belong? The ascribed wealth and value would be transferred to “developing” nations for their own societies to experience and benefit. My initial appreciation turned into rage as I connected the contextual relationship of the histories and the memories associated with sacred “artefacts,” which were clearly nonexistent in their representations.

“Museums want to be sites of memory and indeed they are, but something is amiss when they blatantly disregard the context of the memories they house.”

My heart ached even more when I further examined the ethos of ethnographic museums, and realized that removing the context of these heritage and historical pieces are deemed necessary in the creation of exhibitions as art. Museums want to be sites of memory and indeed they are, but something is amiss when they blatantly disregard the context of the memories they house. The below quotes from Anthony Shelton in his chapter on Museums and Museums Displays, contributed to my befuddlement:

Genealogical narratives ignore specific chronological histories and memories and collected objects are explained by attributing the activity of collecting to a common, archetypal, psychological complex, museums appear to de- and retemporalize objects and exhibitions in accordance with modern period met-narratives…

An object is nothing unless it is part of a collection. A collection is nothing unless it can successfully lay claim to a logic of classification which removes it from the arbitrary or the occasional…

Museums convert rooms into paths, into spaces leading from and to somewhere...

As if the removal of treasures from societies were not enough, their histories and memories needed to be scrubbed and whitewashed into nothingness for “beauty” to be attributed. Decontextualization became necessary to dissolve the responsibility of the atrocities which occured to obtain the “artefacts.” The oversimplification of cultural and heritage material is necessary to now ascribe relevance; the relevance held by its owners is inconsequential. Replacing the violence and identity of the material with new relevance that assigns worth to your Eurocentric view of artistic and culture just adds salt to the wound.

...And so, I leave you with food for thought, in the vein of Selassie I’s and Bob Marley’s teachings:

Until the philosophy that your art is culture and my art is “craft” is finally and permanently discredited and dismantled, you should also be poor. Especially since your wealth was built on the backs of societies, which even up to today are still working to demolish white supremacy, which has engrained your “superiority” for centuries. Until the ideology that my culture can’t live in my country no longer exists, you should remember that my heritage cannot be shared. Until we share our lived, unapologetic, unsanitized histories and start healing those traumatic experiences which have disenfranchised and othered the global south, our heritages can’t be shared. Until the realization and recognition that my heritage must not and should never be diluted for your entertainment and proliferation of the financial, spiritual and cultural poverty of non-Western societies, there should be a war on the ethics of ethnographic museums and the Eurocentric canon of anthropology.

Cherrypye (she/her), a designer, writer, and marketing strategist from the Caribbean twin island of Trinidad and Tobago. A success story from a marginalized and impoverished community, her drive is to inspire other young people, especially girls, to achieve their dreams. Dearly departed from the corporate world of advertising, she is now flexing her design muscle as a visual communications specialist by combining artistic practice, business acumen, and storytelling traditions. A common thread in her design practice is creating Caribbean stories in an authentic Caribbean voice, respecting the past while looking to the future to sustain our stories, and using accessible formats to share these stories.

This text was produced as part of the Troublemakers Class of 2020 workshop.