When the artist, designer, historian, and activist Bahia Shehab developed the Graphic Design program at the American University in Cairo (AUC) in 2011, she envisioned a course for which no textbook existed: Arab Graphic Design History. Despite a few monographs and publications on specific topics—such as political posters, Lebanese design, Arabic typography, and more; at that point there was no student-oriented volume presenting a historical overview of graphic design produced in the region.

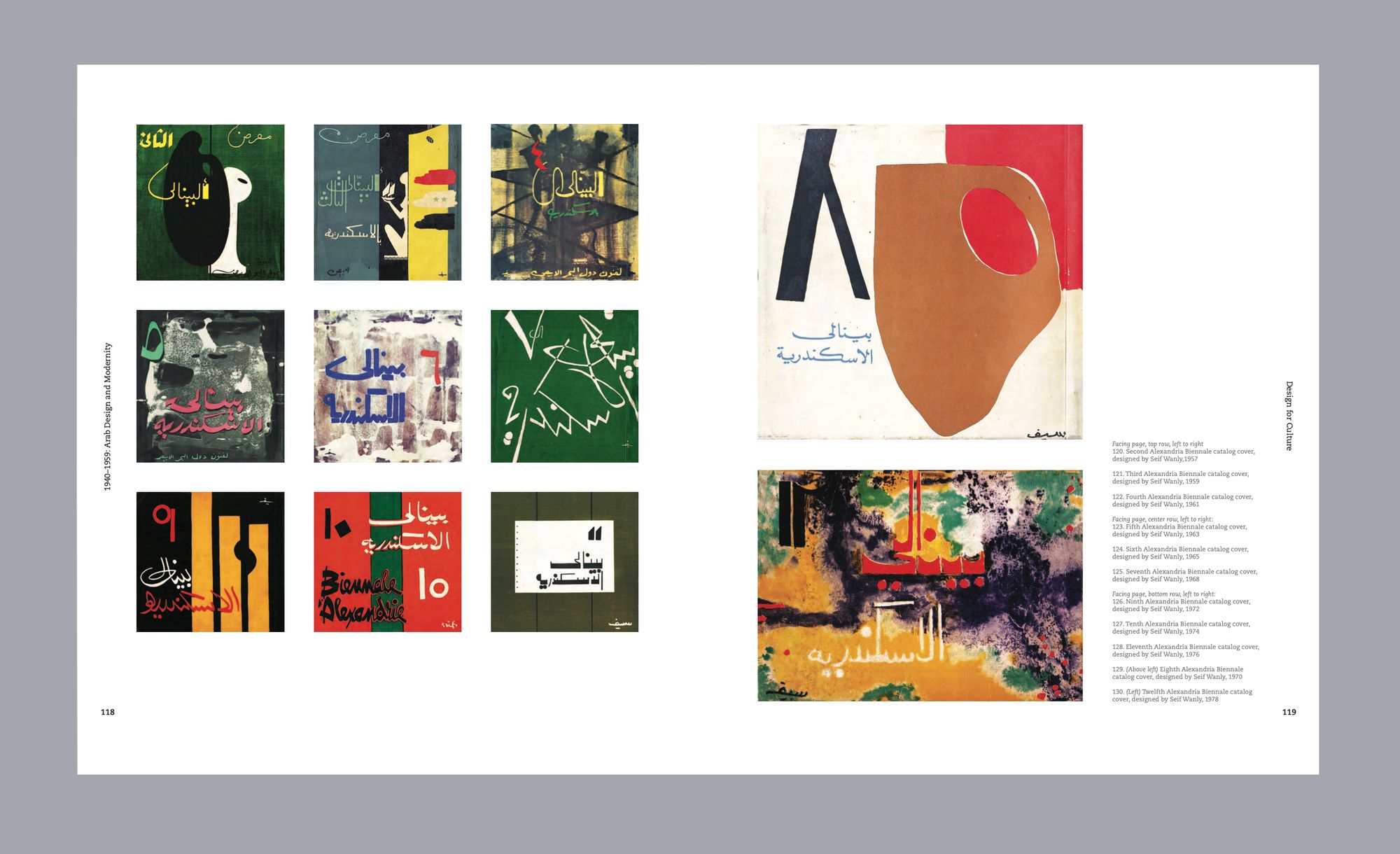

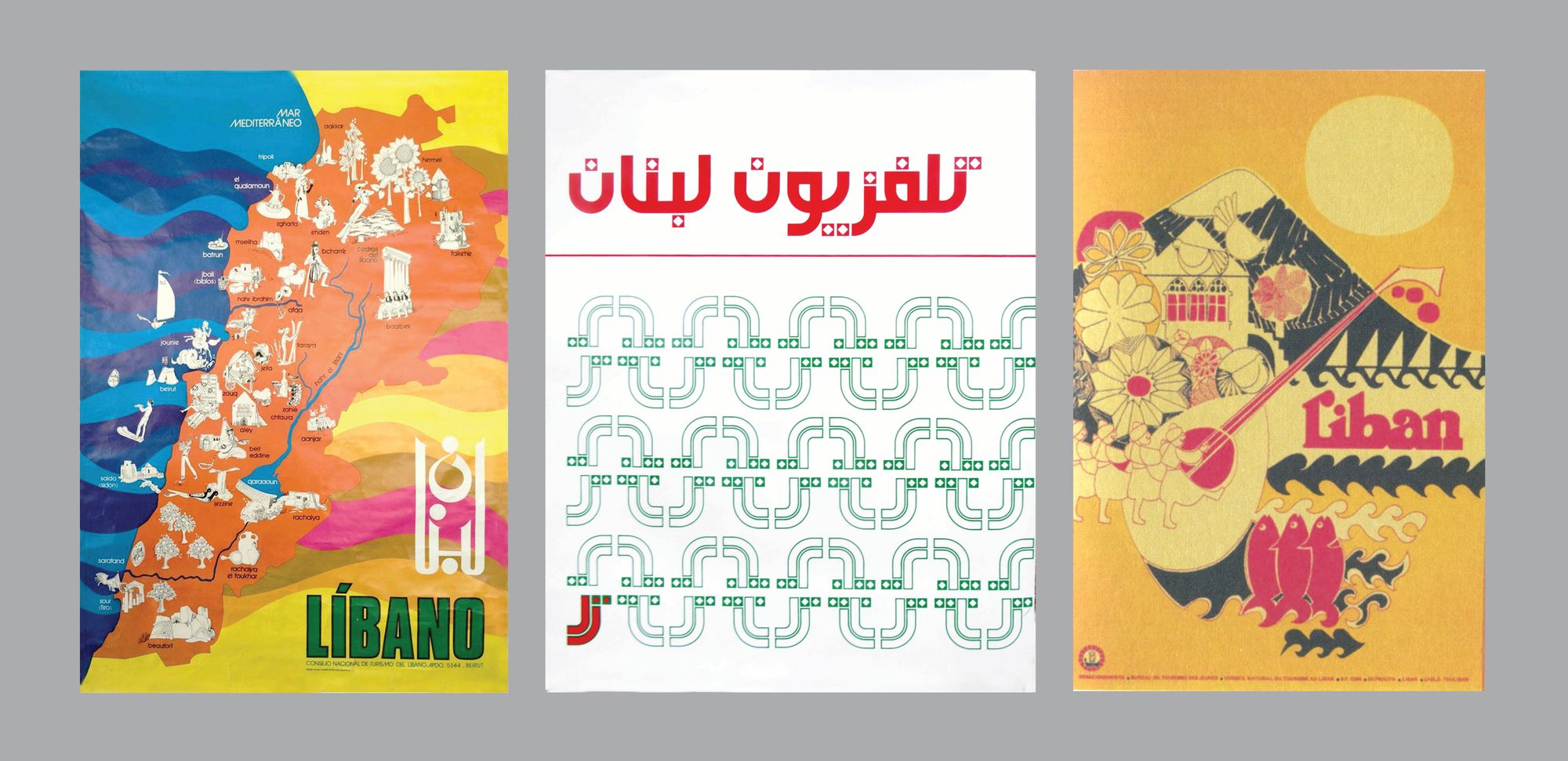

Three years later, the artist, designer, and educator Haytham Nawar joined the AUC faculty. Discovering many interests in common, Shehab and Nawar quickly decided to co-author a history textbook for their program. After four years of work, the result finally appeared at the end of 2020. With over 370 pages and 600 color illustrations, A History of Arab Graphic Design is an invaluable resource. Dedicated “to all the forgotten Arab designers,” the book is still far from being a complete overview. On the contrary, as the authors state in their introduction, it is “just the tip of the iceberg,” which they hope will prompt further research.

Despite its broad scope covering several countries in the SouthWest Asian/North African (SWANA) region, Egyptian design is understandably at the center of the volume. Also, in terms of gender representation, the book features only four (4) female designers against seventy-six (76) men. “The Women of Arab Graphic Design should be coming out next,” Bahia Shehab said in a recent interview. Pitfalls and shortcomings aside, there is something empowering about two educators teaming up to rescue histories neglected by history.

In the following interview, Haytham Nawar discusses the process of making the book, its many challenges and discoveries, as well as how the authors hope it will inspire generations to come.

Ghalia Elsrakbi: How did you form the idea for this project, and what was the motivation behind it?

Haytham Nawar: After nearly twenty years in academia, researching and teaching graphic design, I was aware of the gaps in the history of graphic design of the Arab world. My studies in Switzerland and the U.K. focused on a history of art and design from a purely European perspective—there was almost no mention of design from the Arab region. So when I started teaching graphic design in Egypt, I searched for references, but I didn’t find much about Arab graphic design in current design history books.

“there is an urgent need to write our [design] history from our perspective as Arabs, as people who were born on and lived on this land.”

While teaching at the School of Design at Polytechnic University in Hong Kong, I noticed that the local histories of design in China, Japan, and Korea shared a similar problem. Once, on a trip to São Paulo, I visited a bookstore, where I found a giant book—more than 1,000 pages—on the history of graphic design in Brazil. It was surprising to discover such a rich body of knowledge that is entirely absent from Western design history books. These experiences reinforced the conviction that there is an urgent need to write our history from our perspective as Arabs, as people who were born on and lived on this land. My colleague and the co-author of this book, Bahia Shehab, also already had this same perception. After I joined the AUC in 2014, we decided to start this project together.

How did the concept eventually develop into the book?

It grew out of Bahia’s course on the history of Arab graphic design at AUC, as well as my own experiences. We applied for a research grant to travel to various Arab countries to conduct field research and look into archives. We had to meet people, interview them, examine their work, visit publishing houses and newspapers, and much more. We started in 2016, and it took about two years before we could even start writing the book.

What difficulties did you face while working on this project?

Generally speaking, historically, in our region, there is no real culture of archiving. Well-documented materials are scarce. So, first of all, we were looking for archives that seldomly exist. Only very few individuals in the Arab world have preserved their work. Also, our states do not systematically archive [graphic design] for various reasons, and several of the state archives that do exist can’t be accessed by the public.

“in our region, there is no real culture of archiving. Well-documented materials are scarce. So, first of all, we were looking for archives that seldomly exist.”

Some practitioners actually undervalue graphic design: these might be artists who were forced to do commercial work on the side to generate additional income, so they didn’t care to keep everything documented. One person we approached only wanted to be recognized as an artist, not as a designer.

Another challenge we faced was a culture of conspiracy. People are always suspicious, always thinking that there must be a ‘hidden agenda’. Talking to some people—families of the artists or the designers themselves—was often challenging because of this lack of trust. Some people explicitly refused to collaborate. The son of a designer from Iraq, for example, refused to provide any information about his father since he was unsure why researchers affiliated with an American University wanted to publish a book about Arab graphic design. Another person didn’t want his name connected to some of the political posters he’d designed. Another refused to be included because he didn’t want his name to appear next to other names in the book. As we have experienced, not everyone is open to talking to researchers and scholars. That was something we had to overcome by explaining the nature of our work, why we were interested in the subject from a graphic design angle, and why it is important.

Given that your search extended across several countries, how did you deal with obstacles related to travel, freedom of movement, and access?

It’s extremely difficult to travel from one country in the Arab world to another, due to the political instability and the wars that have broken out since the Arab Spring began in December 2010 [including the rise of Daesh]. It was very challenging to obtain a Moroccan visa. I couldn’t go to Syria, though Bahia managed to get to Damascus because she has a Lebanese passport and could cross the border by taxi from Beirut. We didn’t manage to travel to Sudan or Libya. Obtaining a visa is not easy, but it’s not impossible either—or maybe we were lucky because we’re academics. It was sometimes easier for us to obtain a visa for France or the U.K. than for some Arab countries.

Luckily, we live in the age of the internet, so we were able to communicate with people from different countries by email and conduct interviews via Skype. Sometimes we needed to hire assistants to gather material on-site, scan documents, etc. We covered a lot, but there is still much more to do, and maybe in the future, we can get more access. Now that the book is out, we hope it will help open doors for future projects.

The book introduces many relatively well-known designers but also some more unknown names. What distinguishes the works included?

After dividing the content chronologically, we realized that the book also reflected the sociopolitical, economic, and cultural events that shaped the history of the Arab world. We initially structured the book by dividing the designers into four generations. We used the umbrella term “Arab designers” and did not separate the names by country. We also used an interdisciplinary approach to graphic design, not a rigid definition of the field. Maybe 90% of the names we selected are recognized artists who also practiced design.

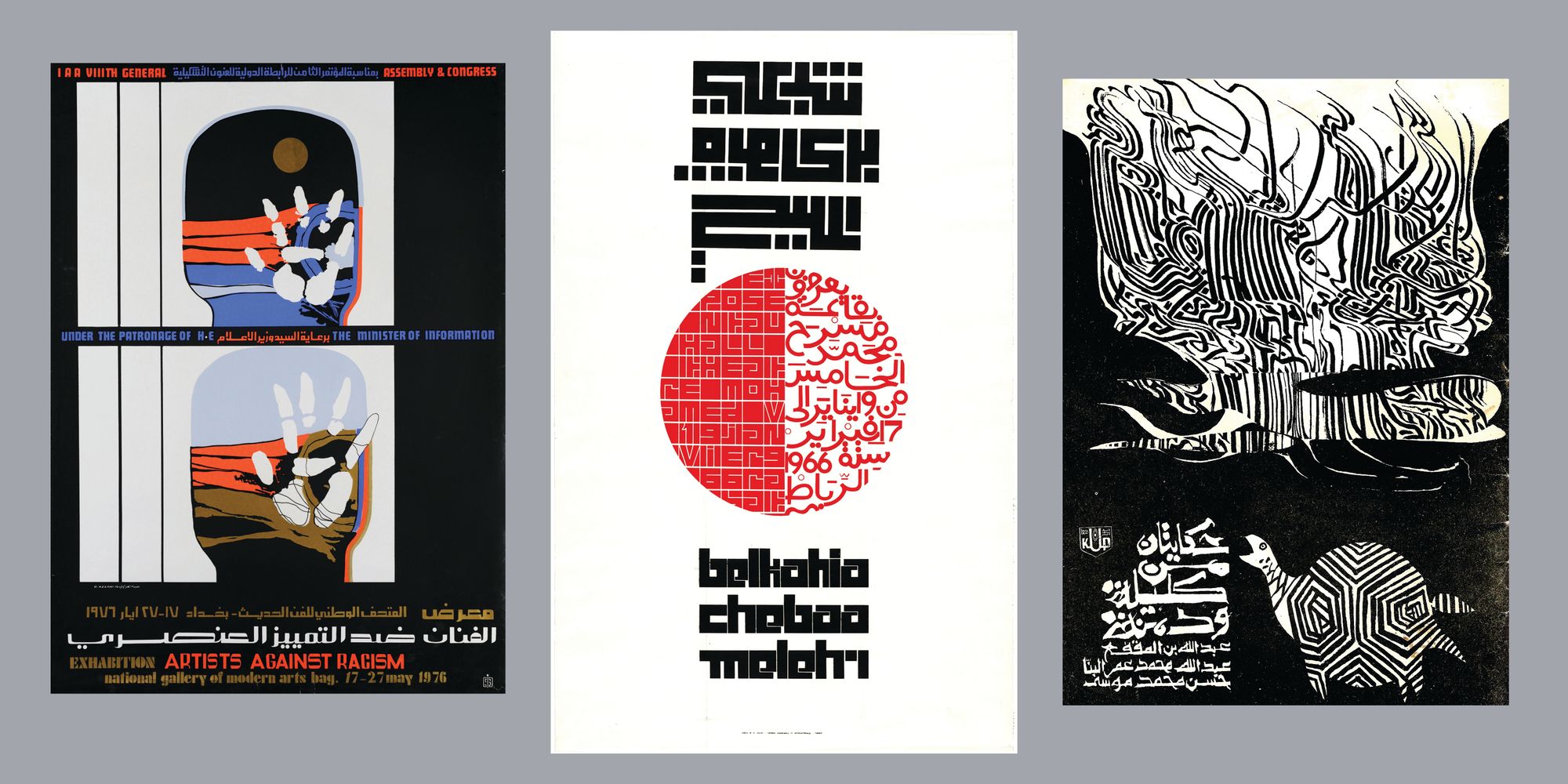

Many art movements contributed to graphic design, such as the Casablanca School in Morocco or the Khartoum School in Sudan. We also included designers associated with important historical events and movements, which cannot be classified within those generations. This means finding contributions from the entire Arab world, for example, around one single cause, such as the Palestinian.

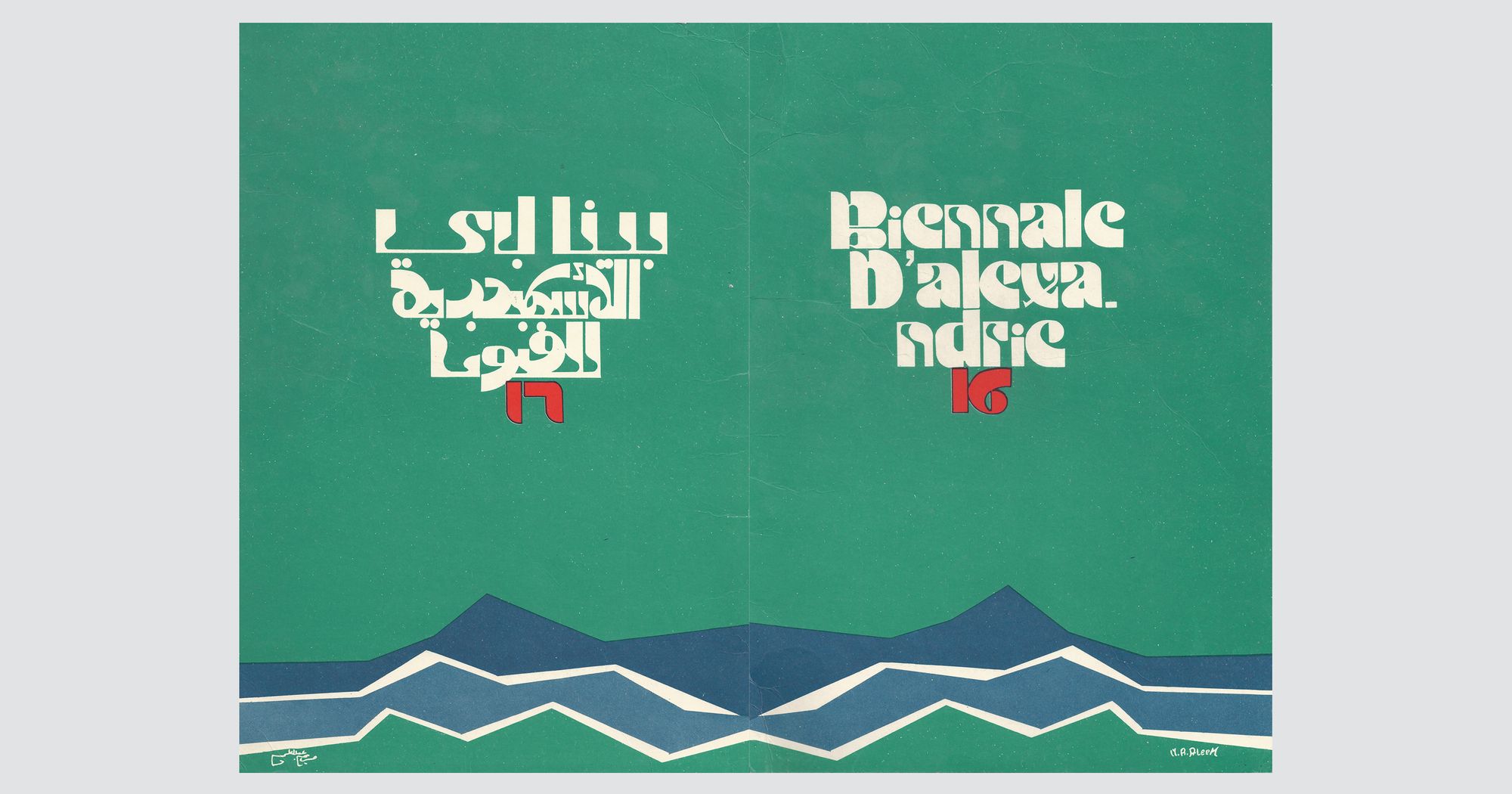

Additionally, we highlighted names that contributed to national projects or cultural events that shaped history, such as the Alexandria Biennale, the Baalbek music festival, and other Pan-Arab projects. Also, we included journalism, as many designers came from periodicals such as the Egyptian magazine Rose al-Yūsuf, or the Egyptian newspaper Al-Ahram.

What was the methodology adopted to document and verify information and sources?

First you look for archives and names. Then, you find out if that person or their family is still alive and if they have any original work. Once you’ve found the work, you need to document it and conduct interviews. When it comes to design education in the Arab world, you need to verify the names of art schools because some of them may have changed during the twentieth century. You can easily connect dates and individuals to the broader sociopolitical and cultural history. You can look in archives for the advertising of the time. There’s also field research, including observation, interviews, collecting photographs and videos, and sometimes searching internet platforms. In terms of the writing, it’s descriptive, analytical, and a survey of historical content.

The book take us on a journey through time. How would you describe the roles of the designer and their relationship to society during each of these periods? How do you compare it to the roles of Arab designers today?

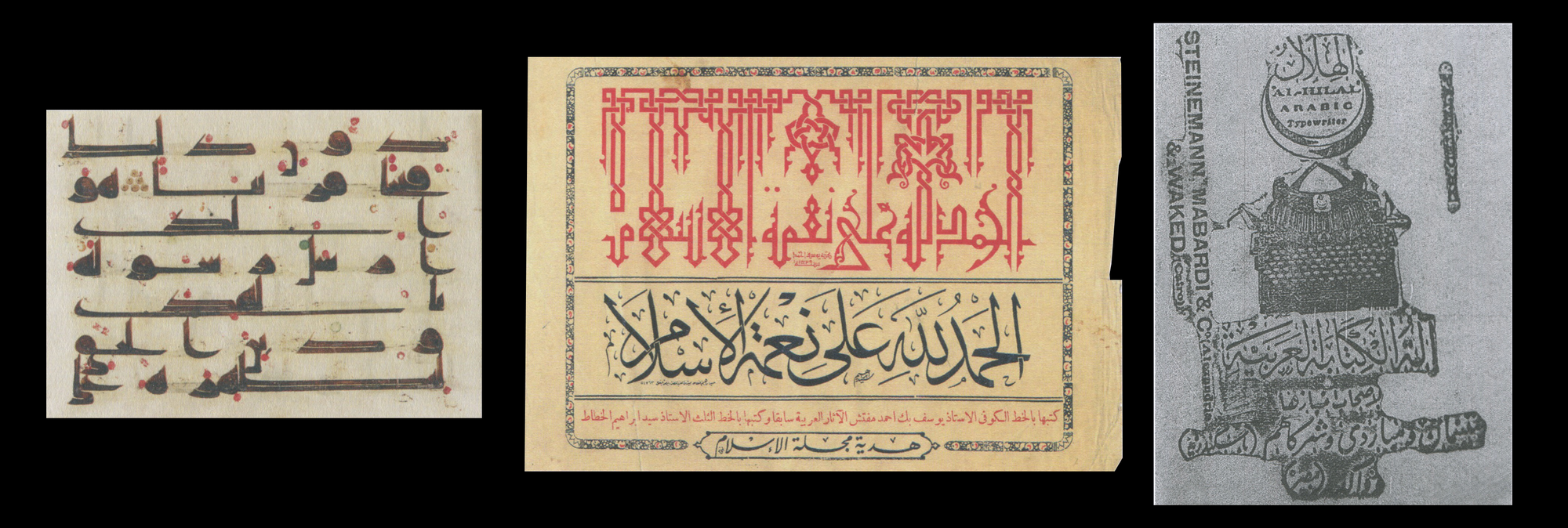

We begin with design before the 1900s, which provides insights into what will inspire the first generation of Arab designers, such as Islamic visual language and early Arabic printing. Then we look into the period between 1900–1919, when calligraphers, printmakers and artists worked before the field was even called ‘graphic design’. We also discuss early Arabic advertising and the foundation of the first art and design schools in the Arab world.

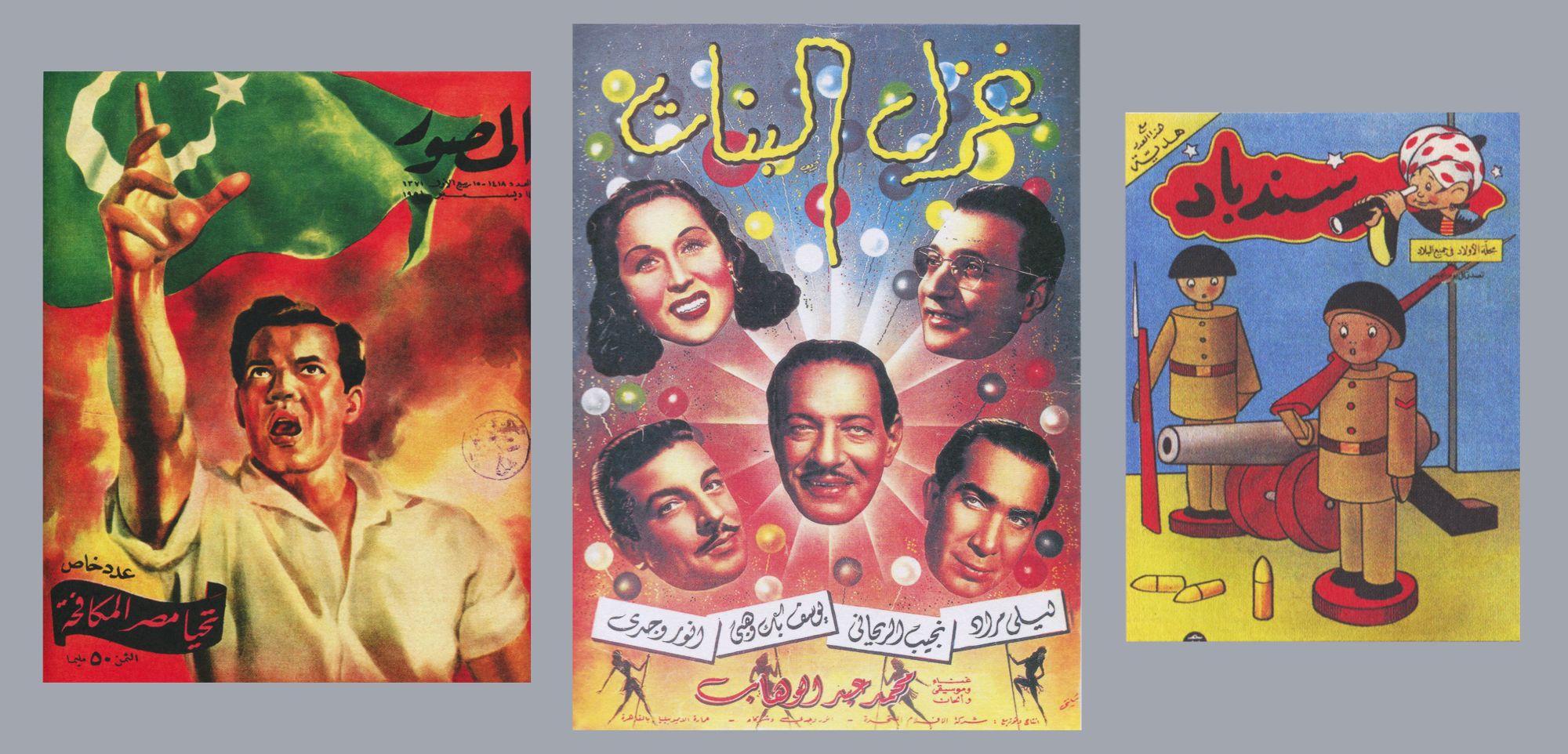

Between 1920–1939, we see the formation of Arab magazines and newspapers, and we examine how technology helped to design for the masses. We also talk about the invention of Arabic typewriters and how it affected Arabic type design. The late 1920s and 1930s also saw the beginnings of Egyptian cinema, and consequently, designs began to shift into a vernacular language that addressed the general public. The so-called pioneers appear in the late 1930s. Here we highlight contributions of interdisciplinary Egyptian designers such as Abdel Salam el Sherif, who worked for the film industry, newspapers, magazines, and publishing houses; as well as Hussein Bicar, who was an art educator, a journalist, an art critic, an illustrator, and a children’s book artist.

Then, you come to the period between 1940–1959, which was very important because that’s when most Arab states gained their independence. Socially and politically, the mindset of designers changed. They began to explore ways to promote the Arabic language through the Pan-Arabism of the Nasser period. We also highlight the work of Sudanese graphic designer Osman Waqialla, who started working in the 1950s.

After this, in the 1960s, there was the emergence of the resistance poster. Once again, you see contributions by designers of several Arab nations—Palestinian resistance posters are a great example. During this period, you can also see how cities like Cairo, Damascus, Amman, Baghdad, Tunis and Rabat become centers of knowledge. We speak about a second generation of designers, such as Hassan Fouad and Abdelghani Abou El Enein.

Then we move on to the 1970s and 1980s, which is the age of exile. We talk about designers who left Lebanon at the wake of the Civil War, as well as the emergence of the Syrian design school. Later, with the Gulf War, there was a huge wave of immigration that led to the spread of Iraqi designers all over the world. We also talk about Arab-African design and North African schools, especially in the Maghreb. We then look at a third generation of Arab designers: those from Egypt such as Mohieddine el-Labbad and Helmi El-Touni; those from Syria such as Burhan Karkutly and Abdulkader Arnaout; those from Palestine such as Kamal Boullata; and those from Iraq such as Dia Azzawi. We highlight many other designers, for example Mohammed Melehi in Morocco.

Moving into the 1980s and 1990s, we talk about the search for a new identity, the emerging field of Arabic typography, and the return of émigre designers back to Lebanon. We also discuss Sudanese designers such Hasan Musa, and related cultural events after the open-door policy of the presented Anwar Sadat in Egypt. Then, you have a fourth generation of Arab designers, such as Kameel Hawa and Emile Menhem from Lebanon, Youssef Abdelke and Mouneer Al-Shaarani from Syria, and many others.

In the final chapter, we focus on the so-called ‘rebirth’ of Arab design between 1990–2000. We talk about the post-Civil War period in Lebanon and how it inspired talented young designers. Then we highlight designers who are inspiring the next generation. They are the future.

I feel the need to take you through these generations so I can answer your question about the role of the designer. Looking back at this journey through a hundred years of graphic design in the Arab world, you can see that it changed with the sociopolitical events that shaped the region’s history. Today, there is a gap. We partly lost what we call Arabic graphic design, which is mostly related to the Arabic language in each Arab country with its individual cultural significance, and we want to bring it back.

“Because of various political reasons, we were completely driven to Western educational systems and visual cultures that affected our creative and professional practices. Designers nowadays need to start by digging into their history to enrich our design practices with our own heritage.”

What is really important to the designers nowadays is to use and speak the language of Arab graphic designers. Because of various political reasons, we were completely driven to Western educational systems and visual cultures that affected our creative and professional practices. Designers nowadays need to start by digging into their history to enrich our design practices with our own heritage. We have a rich history, and we need to be proud of it and integrate it into our new creative practices. The designers of today have more tools—so they need to use them.

Through your research findings, how do you see the development of design education in the Arab world over time?

In the book, we discuss the tradition of art schools from various periods throughout history. After the independence of the Arab states, the schools drifted away from Western educational systems, mostly because of the pushback against colonialism—colonialism was of course present in the curriculum of art schools. The return of Lebanese artists, designers, and educators led to the establishment of new systems. Notably, many private and even public schools are increasingly interested in the emerging field of graphic design.

“After the independence of the Arab states, the schools drifted away from Western educational systems, mostly because of the pushback against colonialism—colonialism was of course present in the curriculum of art schools.”

What is the importance of similar research projects in developing the current design education approaches?

If you look at it from a pedagogical point of view, design is mostly about solving problems related to the community. You cannot separate design from society, politics, economy, and culture. Connecting design curriculums and field research to society, to the community, is the best starting point—and will help in applying this approach to various professional creative practices. That's the best educational practice, I would say.

“You cannot separate design from society, politics, economy, and culture. Connecting design curriculums and field research to society, to the community, is the best starting point.”

Now is an excellent opportunity because—although we have different kinds of challenges—at least from my point of view, the time is now, the future is here. We need to act fast. We are fortunate to have the human resources we have, the great minds which will make our mission easier—but regardless, the future is ours. Our design program at AUC focuses on Egypt, the Arab world, and the Middle East. We rewrite the history of that region and show the importance and richness of our cultural heritage. We aim to establish a relationship between the educational institution and society at large.

How can individuals and institutions help revive graphic design stories in the region?

We need to tell people that graphic design is important. We need to open archives. We need to show the community how design is part of—and adds to—our visual culture. We need to encourage writing about design, educate the public about design by organizing design events, and persuade museums and galleries to host more exhibitions. People need to see how design relates to everyday life, how it's connected to the community, and that it's not just a tool for capitalists or corporations.

“People need to see how design relates to everyday life, how it's connected to the community, and that it's not just a tool for capitalists or corporations.”

The book was first published in English only. Is there a reason for that? Are you planning on making an Arabic edition?

Yes, the Arabic edition is planned. We signed a contract with AUC Press to first publish the book in English, because our main mission is to spread the knowledge about our history internationally. People worldwide need to see that we have a rich design history, and that, for a whole century, Arab graphic designers produced graphic design. At the moment, the most commonly used language in the design field is English. But if this book is to be taught in state universities in the Arab world, we will of course need an Arabic version. We’ll likely see a French edition coming as well, and possibly other languages too. Everyone should be able to read it, after all.

Futuress updated the interview on 09.10.2022. The previous version said, “It was sometimes easier to obtain a visa for France or the U.K. than for some Arab countries.” We amended it to clarify that the interviewees speak about their particular experiences and don‘t provide general information on visa procedures. So now it says, “It was sometimes easier for us to obtain a visa for France or the U.K. than for some Arab countries.”

Ghalia Elsrakbi (she/her) is a Syrian designer and researcher. She is an Associate Professor of Practice in Design, the Director of the Graphic Design program at the American University in Cairo, and co-founder of Foundland Collective, an art and design research practice based between Cairo and Amsterdam.

Haytham Nawar is an Egyptian artist, designer, and scholar. He is an associate professor of design and the Chair of the Department of the Arts at the American University in Cairo. Nawar is also the founder and director of Cairotronica, Cairo Electronic and New Media Arts Festival.

The Bayn Journal originally commissioned this interview, which will appear in their first issue, forthcoming Sprint 2021.

Edited by Rasha Dakkak, Bayn is a bilingual (Arabic-English) annual graphic design journal that advocates the pressing need to establish a dialogue between theory, history, education, and practice. Bayn, which means “in-between” in Arabic, focuses on the relationship between graphic design and other subject areas and its presence in the everyday. Existing discourse locates certain cultures at the core of civilization while "others" remain at the periphery or even outside the scope of history. Bayn is driven by the ambition of revealing to knowledge what so far has remained hidden while nurturing an inclusive environment that stimulates and supports the graphic design discourse in the Arab world.