Barish. Monsoon. A four-month pop-up nature exhibition. In just a matter of weeks, everything that was dry and brown suddenly turns lush green. In India, water and rivers have always been celebrated with festivals as the monsoon ushers life into the once-dry river beds and dormant biomasses. Barish, which means “rain” in Hindi, is much more than a change in seasons—it’s an emotion.

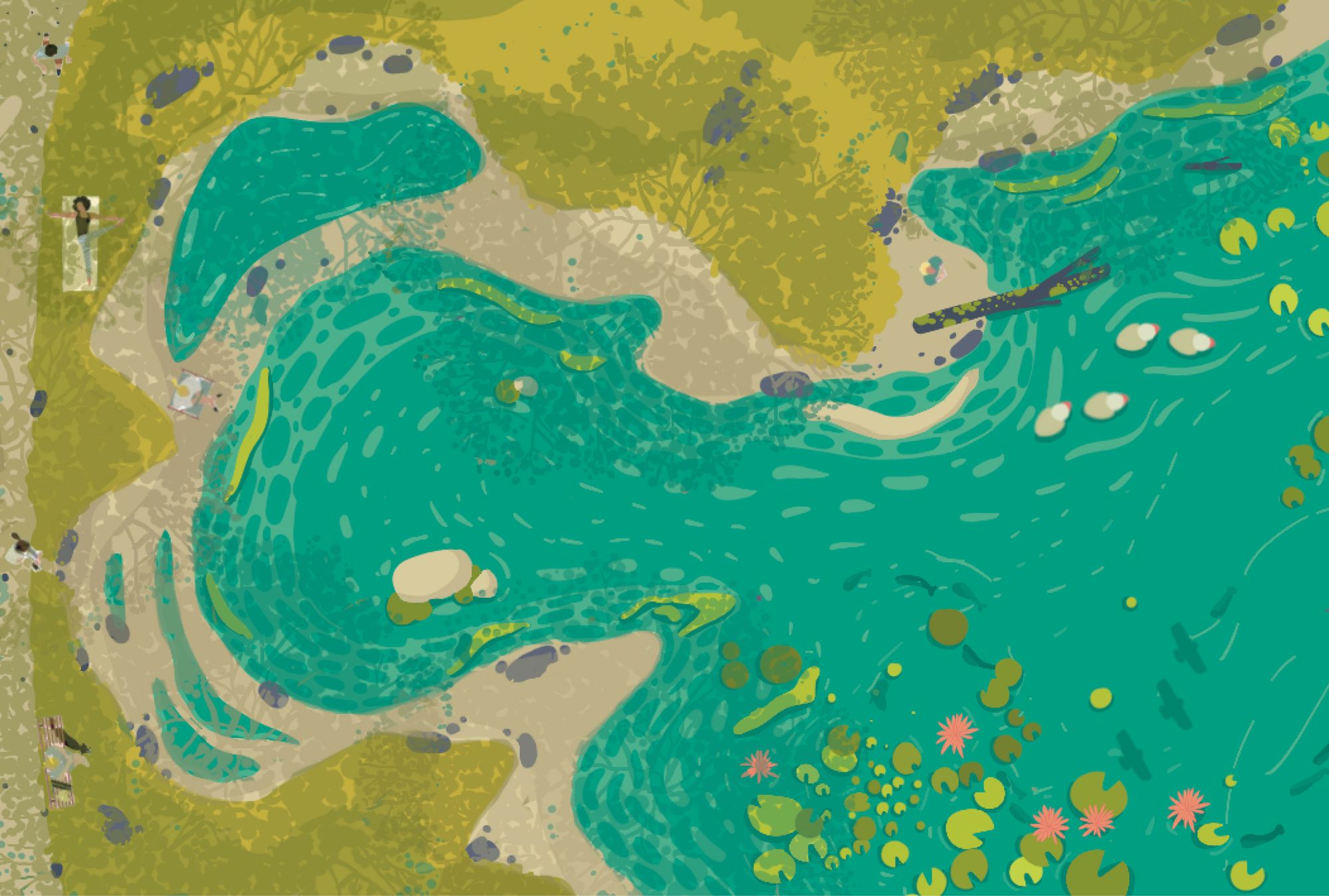

In fact, architect and planner Dilip da Cunha aptly described India as an “ocean of rain.” In his book The Invention of Rivers, he also traces how the very idea of rivers has been culturally constructed. Rivers are ever-changing malleable entities, but maps—which are often based on static pre-monsoon moments—tend to create the illusion of steadfast constancy. Over the years, humans have modified rivers by damming, deepening, and dredging them, and many rivers and other water-bodies have now been simply delegated as channels that carry water.

“For centuries, as a community and as part of our culture, we have worshiped and continue to respect water, but as designers, we try to control and tame it.”

For centuries, as a community and as part of our culture, we have worshiped and continue to respect water, but as designers, we try to control and tame it. What was once revered is now viewed as a resource to be manipulated—engineers and hydrologists treat rivers as a pipeline, economists as a marketable commodity, and the construction industry regards them as a source of construction material. Indian researcher Ramaswamy Iyer further explains the multi-layered view of the rivers and their floodplains considered by developers, planners, designers, and governments as “land waiting to be used.” Floods, with which we once had a symbiotic relationship, are now regarded as disasters that need to be controlled. But how did this change of perception take place?

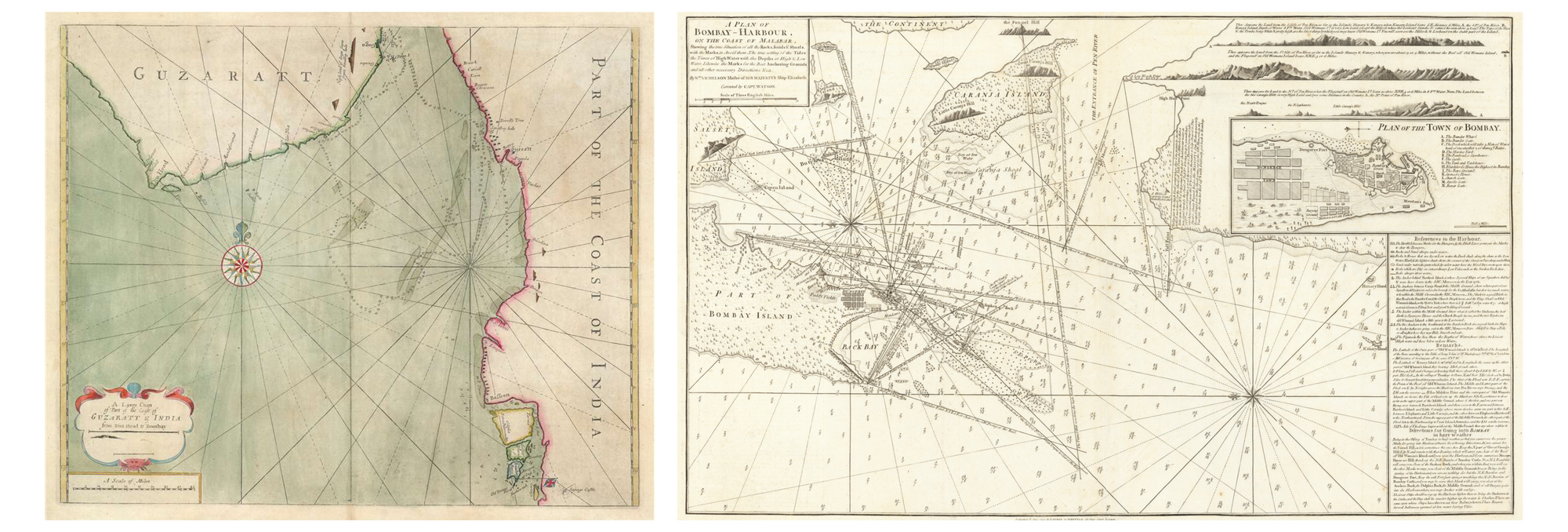

Mapping of an estuary into a port city

What is now known as Mumbai was ceded to the Portuguese in 1535 by the ruler of the Indian state Gujarat. The land was an estuarine archipelago with mountains towards the north, and low-lying islands towards the South. In their book Soak, architects Dilip da Cunha and Anuradha Mathur tell the story of how Mumbai evolved from an estuary to a port. They question and challenge engineers’, planners’, and ecologists’ conceptions of Mumbai as a port metropolis, and demonstrate how Mumbai may be viewed otherwise.

In an estuarine region, the relationship between land and water is very fluid, and changes with the tides and seasons. Unlike a delta where the river meets the sea, an estuary invites the sea in. The terrain was mapped by the Portuguese with lines, giving static shape to the natural fluidity of the estuary. In the 1670s, British travel writer John Fryer explained the ever-changing phenomenon of these islands as “spots on grounds, as they would appear at low tide and vanish in the high tide.” In 1661, the Portuguese included these islands in a dowry for a royal wedding, giving rulership of the area to the British. According to Indian writer Amitav Ghosh, the British hoped to transform Mumbai into a port city because of its proximity to deep waters and the mainland, making the lines a reality by constructing seawalls and causeways. However, translating map separations into divides of land and sea at beaches, boulder fields, and mangrove swamps would prove to be a difficult task.

The 18th-century European surveyors enforced the stark divide between land and water, making these types of division a commonly accepted reality in India. They labeled wetlands, estuaries and mangrove swamps as “Badlands” or “wastelands,” which they are still known as today. This perception led to these landscapes treating water as an invader, assuming that it encroached on the land and the land should be “reclaimed” by constructing barriers to keep the water out. Da Cunha and Mathur explain how the colonial surveyors employed sophisticated methods to draw rational lines of separation, leaving little room for the appreciation of an estuary’s dynamic and temporal landscape. Today’s Mumbai was made by land reclamation, harbor construction, and complex water supply schemes that do not allow for the fluid landscapes of estuaries and mangrove swamps.

Before colonial rule, most settlements throughout India were designed as harmonious ecosystems between water, land and humans. Indigenous water management systems considered each terrain and its relationship to water, and their solutions varied across the subcontinent. For example, in the Southern Indian villages of Karnataka, there were water retention systems called Keres and Eris. In Western India, indigenous communities built elaborate and intricate stepped wells called Baolis and Vavs to store water for the dry seasons. In the Banni grasslands of the Northwest, the nomadic Maldhari communities built shallow wells called Jheels and Virdas, while the Himalayan settlements developed channel irrigation systems from glacial water harvesting and sharing systems.

All of those examples were constructed and managed by the community, not just as sources of water for irrigation, but also as spaces where people gathered and celebrated festivals. Since colonial rule and due to the increase in population in many cities, extensive land reclamation has been the method of urban development. These signs of progress led to the introduction of administrative water management systems by the state governments which severed the bond between the communities and water.

From city of lakes to garden city

According to ecologist Harini Nagendra, in 1830 there were 19,800 Keres created by the communities in the region of Mysuru and Bengaluru in the Southern mainland of India. The Keres were made in the absence of a perennial water source, such as natural lakes, as a network of interconnected rainwater harvesting tanks. The tanks were filled by embanked streams where the outflow of water from higher tanks flowed to tanks at lower levels. These reservoirs, together with the surrounding lands that were connected by canals, created a tightly-knit ecological system. British historian B.L. Rice noted that the network of lakes and tanks was so vast that it would require some “ingenuity” to identify another suitable place for a new tank without disrupting the present water system. He also added that the building of each tank was tied to a myth, and that these sites were revered and considered to be sacred.

Keres are sites where important celebrations were once held; today, this network of vast reservoirs has been disrupted and now lies in a state of decay. As the population and water demands grew in the early twentieth century, alternative water sources from nearby rivers were explored. In 1920s, Mysuru and Bengaluru began importing water from the River Kaveri over 200km away, with dams and reservoirs being constructed on the river to supply water. When the community’s relationship with nature changed during colonial rule, the Kere infrastructure was neglected and began to deteriorate after the introduction of a piped water system. Having lost their value as freshwater suppliers, the once-community-managed systems of Keres were blamed for causing floods and malaria. Although the indigenous systems were the originators’ settlements that are now cities, the communities turned their backs on the systems.

According to a 2019 report by Landscape Foundation India, the British adopted a “formal” engineered way of engaging with landscape, and people subsequently disregarded the indigenous way of connecting nature with communities. Community open spaces, and agrarian landscapes of millets and tree groves gave way to manicured gardens and tree-lined avenues which replicated the image of nature as seen in European cities. Pre-independence, German city planner Gustav Hermann was appointed to design the city’s roads, landmarks, and vistas, and this soon became the epitome of cityscapes. Post-independence, the newly formed government promoted the idea of development and urbanization centered around creating more “useful” land through landfills and land reclamation projects. In the 1970s, a boom in the information technology industry turned Bengaluru into India’s new industrial hub, and the drying beds of keres were identified as potential sites for real-estate development. The majority of the keres were drained and repurposed for housing, bus stations, golf fields and other city accommodations, with sewage and effluents being diverted to lakes—all of these changes ultimately and fundamentally changing the ecosystem.

“Over the last few years, urban planning and design discourses have attempted to promote a conscious engagement with natural systems. But these landscapes are mostly studied in isolation to their larger ecological and socio-urban contexts, and these discussions are influenced by political and economic demands.”

Today reclaimed land is taken for granted, but a century ago this was recognized as a great engineering feat. However, recently the tide has been changing. Over the last few years, urban planning and design discourses have attempted to promote a conscious engagement with natural systems. But these landscapes are mostly studied in isolation to their larger ecological and socio-urban contexts, and these discussions are influenced by political and economic demands. The landscapes are cleaned up and beautified so that they can be fit to receive capital from private investors—a dilemma captured by the discussion surrounding the Sabarmati riverfront development project.

City of seasonal or perennial rivers

In 2005, a waterfront development project was initiated in Ahmedabad to create a “backdrop of blue vista.” The idea of concrete waterfronts with water throughout the year is inspired by the development of the British Thames, the French Seine, and global ports like Singapore, Shanghai and New York. However, the project fundamentally rejected the identity of the Sabarmati, a typical meandering peninsular river that runs through Ahmedabad, whose flow is heavily influenced by rainfall.

For most of the year, the Sabarmati is dry and can be easily crossed, but it can become a roaring torrent during the monsoon season. A perennial river with water all year is regarded as beautiful, but since the Sabarmati river was seasonal it was considered unappealing and uninviting for recreation. Throughout India, many seasonal river systems are tolerated in their natural setting, but are considered inconvenient for the design of a waterfront and development. So, in order to make the river more “aesthetically beautiful,” it was trained and controlled, through extensive engineering and innovation.

“Rather than acknowledging water and land as valuable resources and their relationship as symbiotic, these [capital-driven] types of design concepts reflect a sense of entitlement: human value for the land, and ways of occupying it, are greater than the need for all lifeforms in an ecosystem.”

This modern feat received much media coverage when the principal designer explained his hydrological concept of “pinching the river” by narrowing its width and diverting water from the Narmada canal. The technique was similar to watering plants from a distance; as he explained: “To reach further, you tighten the grip on the hose, and the water sprays.” The work of narrowing the river required structural and civil engineers, developers, planners, and hydrologists to construct massive retaining walls along the banks, which completely destroyed the riparian ecosystem. Rather than acknowledging water and land as valuable resources and their relationship as symbiotic, these types of design concepts reflect a sense of entitlement: human value for the land, and ways of occupying it, are greater than the need for all lifeforms in an ecosystem. This cultural rift as a result of ecological repercussions of treating the river like a hosepipe has been documented in many articles by the LA Journal and Down to Earth.

Following the apparent success of the Sabarmati waterfront, several cities like Mumbai, Delhi, Surat, and Kolkata have initiated similar projects along their rivers, lakes, and canals. The capital-driven urbanization examples of Ahmedabad, Bengaluru and Mumbai demonstrate how the appeasement of global investors promotes a false image and concept of what “beautiful” and “developed” waterfronts should be. These waterfront projects are designed with the notion of creating iconic public infrastructure in isolation to their larger ecological and social urban contexts. As a result of these design ideologies, water bodies are either portrayed as things of beauty or commodities that supply water; or on the opposite extreme: as disposals of industrial effluent and toxic waste. These strategies have furthered the gap between the community, water, and the landscape.

Where do we go from here?

Is manipulation and exploitation the only way to connect with water? Are these the ways we Indians now interact with water? Over the years, we have obstructed water flows of rivers with dams and barrages, and straightened the loops of meandering rivers. We’ve built embankments along the coast, considering water flowing into the sea to be of no value. With no reverence or connection to the water, we pumped it with waste, pollutants and contaminants, while occupying and reclaiming their floodplains—all the while aspiring to make our rain-fed peninsular rivers similar to the aesthetics of the snow-fed perennial rivers of the West. We have normalized cutting, slicing, modifying and taming every inch of our rivers and water-bodies in the name of development. Do we only view the water-bodies as a backdrop for activities, or are they still respected as goddesses?

“We have normalized cutting, slicing, modifying and taming every inch of our rivers and water-bodies in the name of development.”

I have no solid answer but only more questions for the designers, hydrologists and architects. Is it not possible to imagine a different future combining indigenous knowledge and present technology? How do we solve our water problems without the use of extractive and destructive dams and reservoirs we’ve inherited from colonial times? Can we return to a time where we once again consider the needs of the ecosystems before trying to manipulate and bend our water bodies to our will? I believe we can, and to do so we should take a step back to consider ways of engaging with water. It is indeed ironic that our low-tech, effective, traditional and indigenous systems of water management are being replaced by complex engineered dams, channels and riverfronts. None of these seem to have the intended effect of solving something that was not considered a problem, but an opportunity.

Divya Rathod (she/her) is a landscape architect and design researcher from India currently based in Germany. She is an alumnus of Bauhaus Dessau Foundation, Germany and CEPT University, India. She is interested in exploring how we can design places that integrate society, culture and ecology and has been working on finding qualitative tools for reading the character of a place, as well as modes of comprehending and connecting to places.

This text was produced as part of the Against the Grain Fellowship.

Title image: Illustration by Divya Rathod