I first came across the work of Dominican-U.S. designer Ramon Tejada in early 2019, while working on my master’s thesis about marginalized narratives within design education. His text We Must Topple the Tropes, Cripple the Canon blew my mind. I was drawn by Ramon’s sense of urgency of starting his argument with an imperative call to action. In the text, Ramon urges us to disrupt the design canon and open up the field to design narratives and languages beyond the traditional, institutionalised, Eurocentric, Westernized paradigm of design.

Learning more about Ramon, it became clear how the same non-conformist energy of the article permeates the entirety of his practice as a designer and educator. It was with the same engaging attitude that months later, in December 2019, Ramon agreed to be interviewed as part of my research. We discussed the importance of representation in the classroom, how his ever-growing and widely shared Decolonizing Design Reader came to be, and what it means to puncture design education and make space for all the voices the discipline has long overlooked.

Several months later, the two of us decided to revisit our conversation. In the meantime, 2020 shook our world: a global pandemic, a summer of social justice protests led by the Black Lives Matter movement, and a divisive election followed by violence. All of these events laid bare the major social, political and structural problems facing the United States and the planet at large. Our conversation now felt even more urgent and necessary.

A quick note on design versus Design: we propose to dispense with Design with a capital “D,” which we interpret as that reductive, canonized field. We are interested in engaging with design with a lowercase “d”: a more genuine, authentic, expansive, plural, and representative version of what should be considered design. Throughout this conversation, we refer to both; the capital “D” or lowercase “d” exemplifies the distinction.

Luana Almeida: Your text We Must Topple the Tropes, Cripple the Canon is so raw and direct! What made you write it, and also write it in this particular way?

Ramon Tejada: What tipped everything for me was the 2016 U.S. elections, which were—and somewhat still are—so brutally, physically, and mentally exhausting. It demanded that I figure out how, from that point onwards, I would engage with my world and my community—and for me, that meant my design and teaching communities in particular

I started asking questions (many, many questions). The biggest was “Where do I see myself in this world that I’m part of as a Graphic Designer?” I was born in the Dominican Republic [or, Hispaniola, the land where Christopher Columbus landed and “discovered” America, the “New World”—where the rape, pillage and destruction began on the American continent] and raised in New York City. To this day, I feel that New York’s Design does not reflect all the cultural richness and intricacies of the city. It is still held hostage by modernist, universal, Bauhaus ideals. I don’t see myself in Design history, and I don’t see myself in Design theory. Regardless of the excellent education I’ve had, I never felt represented by who makes Design or sets Design rules.

In 2018, my friend Nicole Killian asked and encouraged me to contribute to a series of texts on queering design education published on the Walker Art Center’s website. I have gotten comfortable writing in a way that ultimately expresses my voice. While in graduate school at Otis College of Art & Design in Los Angeles, I remember having many conversations with classmates, particularly my friends Carlos Avila and Andrew Leslie, about writing in my own voice, and about recording myself. I was hesitant at the time. I did not trust my writing voice. I still don’t always trust my writing, but I feel like I must jot down my thoughts and my perspectives.

“The way we write and talk about some subjects has to shift, especially when it comes to ideas around decolonization.”

We all must do this in the field of Design to shift it out of its complacency and high-mindedness. Now, I’m not too concerned about how my writing might sound to some people. What is good writing? We are taught—or at least I was taught—that an established set of rules defines good writing, but there are many different kinds of writing, not just one. The way we write and talk about some subjects has to shift, especially when it comes to ideas around decolonization. Many of the things that I’m interested in asking have been “nicely” asked a million times before. There is a particular language and posturing that people use to ask questions, that ultimately sow doubt in the mind of the person challenging the status quo. That needs to go away as well.

As I started researching further, so many of the people recommended your Decolonizing Reader. How did that come about?

I started the reader’s current form for a Decolonizing Design class that I was going to teach at Rhode Island School of Design (RISD) in 2018. I wanted to gather a list of materials that I thought could be of interest to students (and myself) to attempt to or to start shifting the design we make.

For the record, I don’t think I will ever teach that class in that form again. Decolonization as a special “topic” in an elective course does not make any sense. Decolonizing (in its most holistic and authentic form) needs to be structurally integrated into an entire curriculum!

The reader is messy. I love the idea of messy design, resisting the temptation that many of us designers have of “organizing” everything through our learnt or “good” methodologies. When we talk about “solving problems,” most designers have no idea of what we are talking about—that actually requires a diverse group of people sitting around a table and engaging with messy and complicated challenges to collaborate with communities.

“Ideas are everywhere; you can pull them from cooking books, from literature, or even from talking to your grandmother. You don’t need a codified, institutionally accepted body of texts that tells you what design is.”

This idea of messy design can be extended to our knowledge, for example, by allowing ourselves to unlearn, learn, and continue being students, by reading materials and ideas from outside the literature of Design. Why don’t we read authors like bell hooks in any design class? Why not James Baldwin? His critique of film is a critique of visual culture. One can draw a through-line from his work to design! Ideas are everywhere; you can pull them from cooking books, from literature, or even from talking to your grandmother. You don’t need a codified, institutionally accepted body of texts that tells you what design is. I have been discussing a lot of these ideas with my friend Silas Munro, who teaches in L.A. Together we formulated a workshop called Throwing the Bauhaus Under the Bus in 2019. We talk a lot about lineages and where you come from as an entry point into developing the work you want to make. I always joke, saying: “Make it for mom and grandma, not for designers.” Maybe that’s the design that is actually even more appropriate for us today: making design that is more local to your community.

More recently, we have been talking about the idea of going back home or “Sankofa” through a series of BIPOC Design History classes that I have been participating in, led by Silas and his collaborators Tasheka Arceneaux-Sutton and Pierre Bowins. It’s a community of designers, teachers, and students learning collaboratively about the ideas, works, and perspectives that have not been valued and elevated in the Design canon.

It’s very important to make space for questioning this approach, but the reality is that most students don't think they are in a position of questioning.

Yes. This is a challenge, as we have to really engage with each student to encourage them, and help them to develop their confidence, their perspective, and their point of view; and to understand how important it is for them to ask different kinds of questions on their own terms. I would say that in this respect, history is not on our side. Design as a professional discipline is only about a hundred years old. Its history has always been tied to this idea of problem-solving, and it has been very immersed in regimented, systematized, universal ways of thinking and hero worship as a means to solve problems.

“I have been exploring the idea of leaving spaces in the syllabi where students can physically see that there are gaps where they can enter. This way, the interaction is not just one-sided; it is open and collaborative.”

Yes, and especially when we frame this in the context of design pedagogy, not having space to discuss established ideas is extremely problematic.

I have been exploring the idea of leaving spaces in the syllabi where students can physically see that there are gaps where they can enter. This way, the interaction is not just one-sided; it is open and collaborative. We also have to always question the language and the terminology we use in the classroom. Some of our language has been problematic from the perspectives of culture, race, gender, etc. Making work while thinking through all of these multiple perspectives (or potential lenses) is very different and may require us to do a lot of shifting. This constant change makes many people uncomfortable, especially those who have been privileged to sit at the top for so long.

Yes. Writing a thesis about design pedagogy and its problems has, at times, caused some discomfort in my department. Proposing to talk more about the way that we do pedagogy was interpreted as pointing the finger at the institution. I think people still get almost offended at being questioned.

People take it personally. They tend to feel that you are attacking their intellectual capability and their status as part of an institution, when in fact all you’re doing is posing questions to allow for possibilities to emerge. These people have often been repeating the same thing, and it’s hard for them to consider that maybe some of the ideas they advocate (or have advocated) are no longer relevant. People’s egos often get in the way—and let’s be honest, no one has time for your ego these days.

In your experience, how have institutions received your approach to a decolonizing pedagogy of design?

I have decided, many times in collaboration with others (friends, colleagues, students, other BIPOC faculty, and administrators), to ask questions and tackle this head-on in my own way. I feel that we all must do this in whichever small or large way we can—in our classrooms, department, schools, and communities. It’s not always easy—and it has been incredibly exhausting this last year in particular—but we still have to ask the questions and demand structural changes. It is about creating equitable access, equitable economics, and opening up broader opportunities for everyone who wants to get an art and design education.

What about your experience in studying design; was it then that you started to engage with your current approach to education?

I started doing Graphic Design in high school, somewhat unconsciously. I really liked playing with the forms, whether it was typographic or visual. However, I did not study Art or Design in college, but theater; and then I became interested in performance art.

When I turned 30, I switched careers. I was just exhausted from trying to do performance work. The cost of education is really high. I had (and still have) a lot of student debt, and lots of jobs that went nowhere. That left me a bit bruised, so I turned this thing that I did on the side, which was Graphic Design, into something to pursue. I went through several cycles of admission processes, and I ended up at the Otis College of Art and Design in Los Angeles.

L.A. was (and is) very experimental. I really loved how the work produced there looked, visually! It didn’t feel as locked down as what I had seen in New York at that time—lots of corporate work that just made me feel like: “Argh, if I see Helvetica one more time, I may just explode!” After L.A., I went back to New York to work as a Graphic Designer and really focused on my teaching. Before coming to Rhode Island, I taught in New York at Queens College, at Pratt Institute, and at Parsons/The New School. I also taught a seminar online at MCAD in Minneapolis. Then, through some universal magic, I ended up at RISD.

How would you define your approach to design education?

In many ways, both my design teaching and my design practice are about talking and engaging with people. The way that I teach is really loose. Also, I don’t do critiques. I am interested in having conversations with students about their work, ideas, and the potential for their work to develop and grow. The word “critique” is one of those that I feel we need to reevaluate and redefine.

As a teacher, the idea of care is essential for the students and ourselves. This means caring about your students; being concerned that they have enough time to breathe, eat, sleep, and also time to think about their work. It means giving them permission to ask questions about the things you are saying. I try to teach so that I can say: “Here’s how I see it (through my experiences)” but still leave the space for everyone to immediately disagree and develop their own approach or way of seeing it. It opens a door for students to understand the value of their perspectives. It is really amazing when students prove me wrong or teach me.

“At a base level, we must critically look at our syllabi. Who are we asking students to read about? Who are we showing them images of? Can they see themselves reflected? Who is not being seen? Why do we talk about specific subjects and ignore others?”

For me, the idea of classrooms as collaborative and welcoming spaces is essential. I also have to model for BIPOC students—the kids who look like me—in the classroom. I have to make sure that students can see themselves and value their work, and ensure that they have the agency to do things. Modeling multiplicity is a responsibility that design hasn’t been very good at in the past; it should be a concern for all of us as educators. At a base level, we must critically look at our syllabi. Who are we asking students to read about? Who are we showing them images of? Can they see themselves reflected? Who is not being seen? Why do we talk about specific subjects and ignore others?

I did my bachelor’s in design in Brazil, and the authors whose texts we were reading were mainly European. However, students need an extra incentive to get to know their own background, and I think this should be done not only in places like Brazil, but also international programs like the one I did in Germany. There should always be space for students to introduce their own culture and see themselves in their education.

Absolutely. That’s the question about colonialism and coloniality: the idea that there is one valid knowledge base, and the rest is not. There is so much incredible, insanely beautiful design in South America, made by people that Design would not call designers. Historically, it has not been considered Design; it was labeled as craft or some other elitist term Designers came up with to denigrate and devalue many peoples’ traditions and narratives. That design is so great, but it’s only deemed authentic when some hipster designer from Brooklyn takes pictures, goes back to their studio, and outputs some cool typeface “inspired” by it.

Be honest: you just went on a trip, appropriated, and stole people’s culture and narratives. You are perpetuating colonialist ideas.

“We can’t use a textbook about design history that is 1700 pages long, and 99% is European history, and one percent everybody else.”

I finished my design theory course with a weird feeling, and only later, I realized that it was because most authors and references had been very Eurocentric, very white, and very male. This was especially troubling in a class where students were very diverse in terms of nationalities and cultural backgrounds. I started a conversation with my professor to understand his choices. In his view, these were topics students should be familiar with before going into practice, and the texts he selected were the ones that received the most recognition—these were the “established” texts. But even if a topic is “fundamental,” there should still be more than one way to look at it, right? There are undoubtedly other authors from different places and backgrounds who also made contributions. Do you agree that the established literature should still have space in the curricula, even if just as a counterpoint?

You have to learn, and learning doesn’t stop when you finish your master’s or your PhD. You have to continually reevaluate. There are so many other readings besides the so-called “established” ones; lessons that may not even be about Design per se, but that enable students to engage with different perspectives or to be confident about the perspective in which they are interested. We can’t use a textbook about design history that is 1700 pages long, and 99% is European history, and one percent everybody else.

“Let’s be honest, some of the ‘established’ texts of design are incredibly problematic.”

Let’s be honest, some of the “established” texts of design are incredibly problematic. For instance, Adolf Loos, a man considered by some to be the forefather of modernism, was a convicted pedophile. His essay Ornament and Crime (one of the “linchpins of Modernism”) is absurdly racist; there is a section in which he calls entire cultures “savages” and “degenerates.” This image seeps into everybody’s head. Arguing that Loos had a singular point about ornamentation while ignoring his knowingly racist discourse is a huge problem.

The tricky part is that sometimes when you are putting a class together, you look at the readings in your bibliography list, and you realize that you’re still doing the same thing! What is accepted has been so ingrained in us that sometimes we don’t question it. I’m not an exception, and often I find myself in that same position. But these days, I am really conscious that I just don’t want to give the platform to some of those ideas and discourses anymore. Someone else can do that. I am taking another path, engaging with others that should be (and should have been) in our classrooms and studio spaces.

I think a lot of students don’t engage with topics such as decolonization because the information around it sounds highly theoretical. Sometimes it feels intimidating to talk about decolonizing design because there’s this idea that only some people are equipped or have the level to discuss it.

Yes, absolutely. Part of the way out of this is dismantling the notion that these ideas are “big things.” They’re actually really quite simple ideas: recognition, acknowledgment, generosity, respect, inclusion, reparation. That almost sounds like a cliché, but we all have to understand that people are different, people have different perspectives, and that it’s okay; we have to be respectful of it. Historically, not only in education but also, more broadly, those who have access to certain things are part of the club, and all the rest just gets discarded at the bottom.

Having a fancy vocabulary is fantastic. Still, I sometimes question the validity of having such an asset if you don’t know how to deploy it to work with people. That’s also how certain people in many fields have maintained their status and control: by locking things down. When you dismantle some of those ideas that we have held onto, you might realize that they don’t help. Those ideas are actually part of the problem.

Luana de Almeida (she/her), is a multidisciplinary Brazilian designer based in Germany. After nearly ten years working in various graphic design domains, she has recently received a master’s degree in Integration Design from the Hochschule Anhalt in Dessau. This interview was originally conducted for Making Space, Luana’s ongoing research about intersectional feminism design pedagogies.

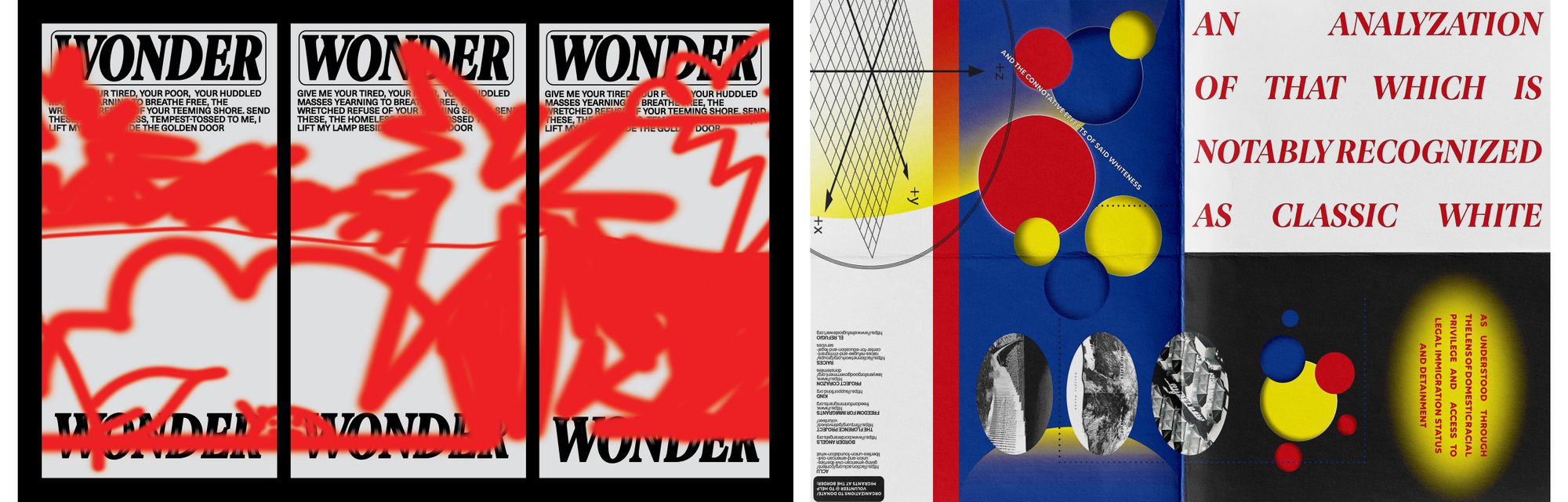

Title image: Soleil Singh, RISD.