“Indian design student” is almost synonymous with upper class, elite, and urban—and from an oppressor caste family. Most Bahujans—who come from marginalized castes, religious minorities, and other underserved communities—don’t feel at home in such educational spaces. In 2015, when my professor asked us to illustrate a poem, I chose Paani (Marathi for “Water”) by Namdeo Dhasal—one of the founding members of the Dalit Panthers, a social movement that emerged in the Indian state of Maharashtra in the 1970s to combat caste-based violence. My choice didn’t go unnoticed, and I soon found myself explaining to the class—an elite, oppressor caste bunch—who my poet was. I was the only one who chose Dalit literature, whereas my peers picked Shakespeare, Wordsworth, or religious Hindu texts by Brahman poets. The verses illustrated by my classmates conveyed Hindu aspects of purity, happiness, and serenity, and were adorned with floral motifs in bright colors. By contrast, my poem described how caste is a fundamental marker in water access and usage due to the violence of “untouchability” that forbids sharing it with Dalits. There are countless examples of Dalit children drinking water from the “wrong” pot or well, and subsequently they are subjected to brutality, and often lynched to death by oppressor castes. In my illustration, I portrayed water as black, harmful, and ugly, as it carries painful memories of brutality, restriction, and lack of access. Sitting among my classmates, I wondered: “Why does no one know about this revolutionary poet? Why are most of my peers oblivious to our casteist reality? And why is India’s hegemonic visual communication so overwhelmingly homogenous?”

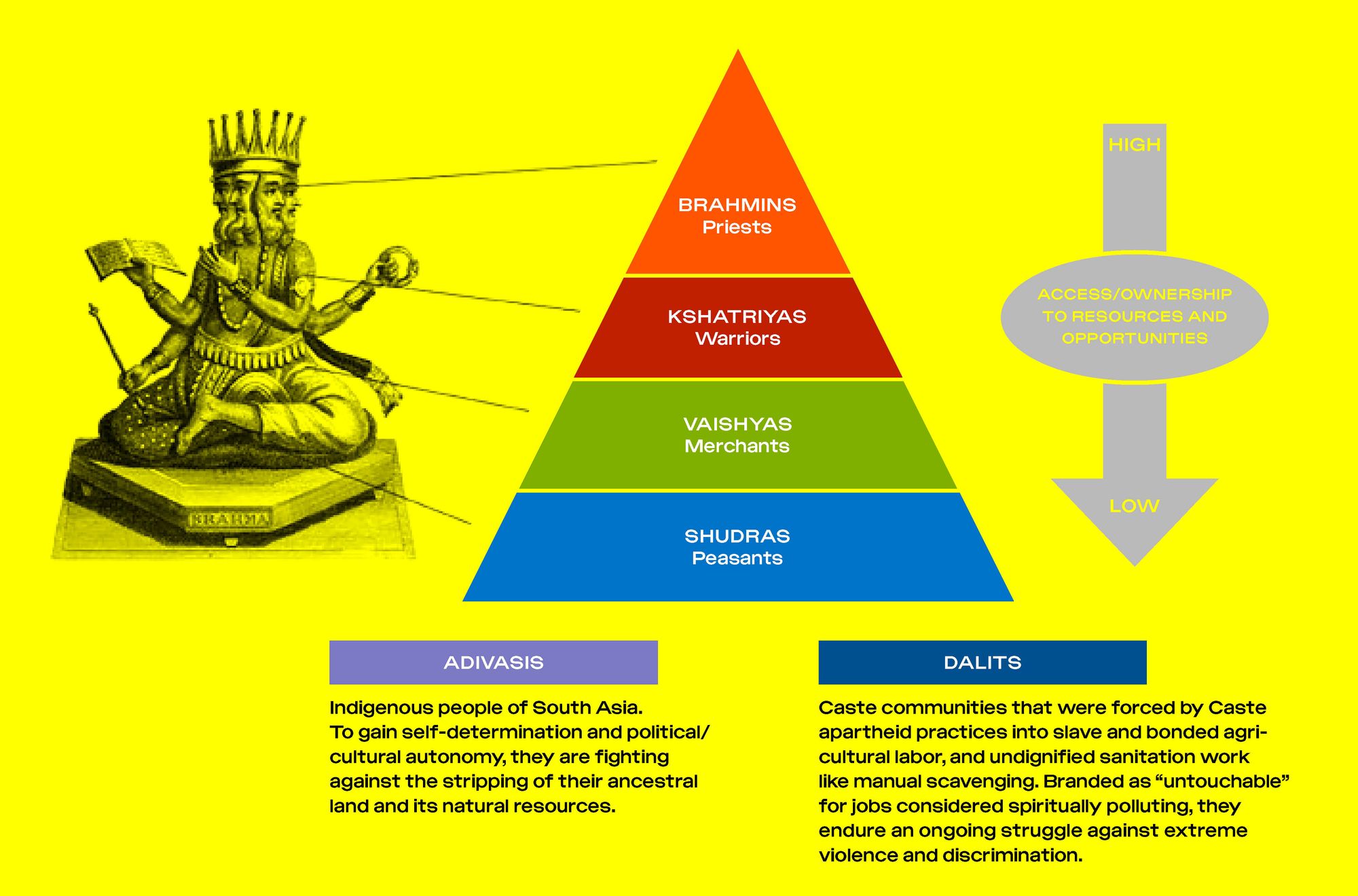

In India and, by extension, throughout the global Indian diaspora, casteism constitutes the fabric of our society. It impacts everything! To understand the casteist roots of Indian design, we must acknowledge that the caste system was not a colonial introduction, nor did it end with the exit of colonizers from the country. Casteism dates back about 3000 years and consists of four caste categories. In decreasing order of “purity,” they are Brahmans (priests and teachers/gurus), Kshatriyas (ruling class, warriors, soldiers), Vaishyas (landowners and traders), and Shudras (laborers, craftspersons, and artisans). Below, there is a fifth layer outside this varna system that consists of the “untouchables” or Dalits/Avarnas/Atishudras and the Adivasis/Indigenous communities. They are forced to work in “impure” occupations—tasks that are ritually, religiously, and socially “polluting.” These include manual scavenging, tidying up toilets and public spaces, cleaning up the carcasses of dead cattle and stray animals by hand, dyeing fabrics, tanning hide into leather, weaving cane baskets, and making percussion instruments from leather, among others.

As Dalit jurist, economist, and social reformer Dr. Bhimrao Ramji Ambedkar says, the caste system is not only a division of labor, but a hierarchical segregation of laborers that Brahmans prescribed in ancient Hindu texts like the Manusmriti, Shastras, and Vedas. The selection—or exclusion from working in a particular occupation—was never based on actual aptitude, competency, or individual choice. Rather, it is a dogmatic authorization by the most privileged and powerful community sitting at the apex of our graded society. They appointed professions to individuals based on the caste of their parents. As defined in the Manusmriti and Vedas, this graded inequality is justified based on karma, a belief that one’s position in this world is ascertained by deeds in their past life.

Casteist logic of Indian design

In the caste system, only Brahmans have access to formal education, which previously consisted of rote learning the Hindu texts to maintain and perpetuate caste hierarchy and priestly duties. Historically, creative production in India never possessed any infrastructure to formally train and educate artisans, laborers, and craftspersons—who primarily belong to marginalized castes. This “skill-based” tacit knowledge—something we designers love to harp on about– is still almost exclusively passed down from one generation to the next according to caste. It ensures that opportunities outside of a person’s caste-based occupation are rarely accessible.

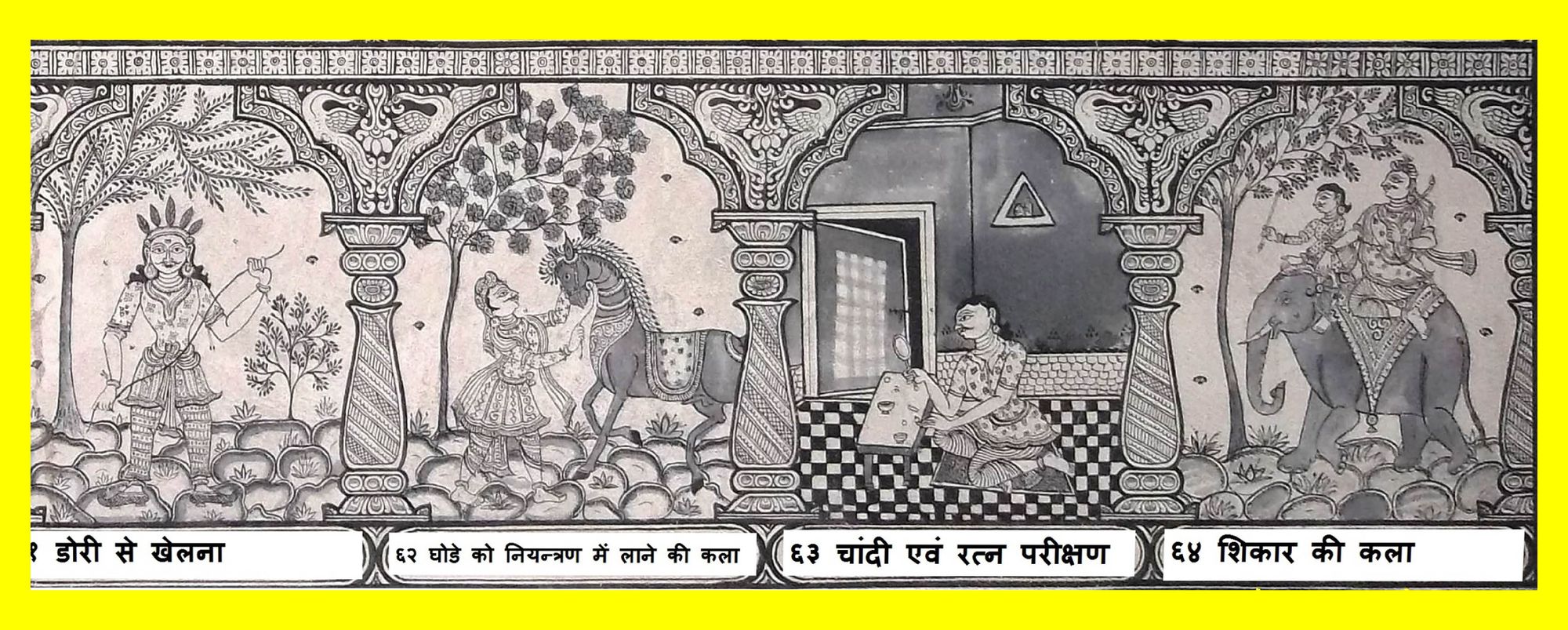

Of course, the rigid occupation-based differentiation doesn’t apply to those above marginalized castes in the schematic pyramid. Those graded “higher” enjoy better professional mobility, with absolute freedom reserved for the Brahmans at the apex. Consequently, the Brahmans freely entered domains of creative production they deemed appropriate and profitable, and defined each art or craft as “traditionally Indian.” Thus, over many centuries, Brahmans designed this philosophy where the “higher” order of a kalaa (artform) only meant the theoretical and aesthetic modalities. For example, tanning leather and creating leather products are not considered creative activities, but sketching out the design of a handbag or a car seat is considered kalaa. This higher order was only accessible to Brahmans since they wrote the Shastras—Sanskrit for “rules, manual, compendium” about these artforms, recorded retrospectively in the Vedas. As a result, they relegated the practical aspects and technical know-how of actual artistic and creative production to a “lower” order. This meant that the creative works of artists, craftspersons, and laborers from marginalized castes were rendered “lower” and insignificant.

In the mid-19th century, the British established art schools in major Indian cities. Marginalized castes were prohibited from accessing formal education by law of the caste system, and only oppressor castes could apply to gain formal training in Eurocentric fine arts and literature. The rise of the Swadeshi Movement—the self-sufficiency movement which formed part of India’s freedom struggle—started by artist Abanindranath Tagore led to the foundation of Shantiniketan in Kolkata. This was the first Indian art school of the modern era. As the Movement gained momentum by the early 1900s, several Indian artists began forging the Brahmanical identity by rejecting the prevalent European art styles. This way, creative work produced by oppressor caste artists became synonymous with the “Indian” cultural identity. Unfortunately, to this day, this nationalist identity continues to define Indianness as synonymous with being Hindu.

Where does Indian design education begin?

After gaining independence in 1947, India’s first prime minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, set in motion the industrial wheels for postcolonial modernism with a vision to secure a place for India on the world map as a developing nation. With a shift from an agrarian economy to an industrialized one, he felt India needed to mechanize the crafts to propel the economy toward modernism, while keeping only a peripheral goal to “save the crafts.” The urge for modernization led to the invitation of U.S. architects Charles and Ray Eames to study creative production in India and analyze how India can encourage “innovation” in design. Bringing in a white couple practicing design and architecture in the U.S.A. meant that India once again interacted with North-American/Eurocentric design values and perspectives, while seemingly keeping the nationalist/Hindu conscience intact. Decisions forged in the spirit of nationalism that was, in turn, analogous to the casteist Brahmanical identity led to the drafting of the India Report in 1958.

If you have read the report, you probably heard of the famous ubiquitous lota. All throughout India, this clay or metal vessel serves to store water for everyday use. Discussing lota in purely aesthetic and functional terms in the report removes it from its fundamentally casteist context. The Report emphasizes the design of the lota that ticks all the boxes of “good design,” thus erasing the existence of caste in India because producing the lota is, in reality, a caste-based occupation! For outsiders like the Eames, this creative production may seem “casteless” since they only look at the lota from a functionalist lens that caters to the need for mass manufacturing of this object. However, this erasure is nothing but an incognizant perpetuation of casteist logic. The Report classifies the lota as the epitome of Indianness. The “Indianness” of the everyday object analyzed from the lens of manufacturing and poverty alleviation intentionally ensures the continuation of caste-based violence, fetishization, romanticization, and erasure. It is worth questioning how Eames assumed that within the so-called democratic practice of design, it was appropriate to insert Brahmanical texts and casteist ideologies! The India Report, which fails to stand for egalitarian design values, begins by quoting the Brahmanical text of the Bhagavad Gita, sealing its casteist value system as it asks the reader to seek refuge in “the knowledge of the Brahman, the Supreme Lord” [sic!].

“Design education followed the notion of modernity coming from the Global North and West, and so-called ‘Indian’ tradition referred to norms established by Brahmanical hegemony, ignoring the casteist roots of Indian design.”

The India Report laid the ground for establishing the National Institute of Design (NID) in 1961 and the beginning of institutionalized design education in India. The Report advocated for a problem-solving design approach that connected classroom instruction with real-world application and saw the designer as a link between tradition and modernity. Design education followed the notion of modernity coming from the Global North and West, and so-called “Indian” tradition referred to norms established by Brahmanical hegemony, ignoring the casteist roots of Indian design. Thus the first generation of NID alumni, mostly from privileged backgrounds, spread across the country occupying key positions in the industry and teaching in newly created design positions. All of this led to sustaining this status quo in all design disciplines, including visual communication.

So what makes Indian illustrations Brahmanical?

The dominance of oppressor caste illustrators has helped to maintain and perpetuate casteist images. This visual language comprises mainly illustrations portraying the celebration of Hindu festivals like Diwali, Holi, Navratri, Dusshera, and the Brahmanical representation of King Maveli when celebrating Onam. Legend says that King Maveli was a generous and wise Asura (mythicized demon) who ruled the state of Kerala. In his kingdom, caste-based discrimination didn’t exist, and the wealthy and impoverished were equally treated. Onam festival celebrates King Maveli’s annual visit from the heavens to Kerala. Despite the non-Brahmanical origin of the festival, numerous illustrations misrepresent the king wearing the janeu (sacred thread worn only by Brahman men) even though he wasn’t a Brahman. The process of “Brahmanizing” Maveli’s imagery draws similarities to the “whitening” of the image of Jesus in European art.

Another element reproducing Brahmanism in India’s visual language is the lotus flower. In Buddhism, the lotus symbolizes the highest spiritual attainment. However, the dominant culture highlights that the lotus derives meaning and significance associated with Hindu gods like Brahma and Lakshmi. In the current political situation, one can say that the lotus is symbolic of fascism as it is the emblem of the governing Bhartiya Janata Party BJP (India’s People’s Party), a right-wing extremist Hindu political party under the leadership of Narendra Modi. Since his rise to power as the Chief Minister in the State of Gujarat in 2001 and as a Prime Minister in 2014, the country witnessed an upsurge of barbaric policies and actions, such as the bulldozing of Muslim homes and businesses, genocidal violence against Muslims, or steeping discrimination and persecution against the Dalits. With rising fascism, the lotus has been appropriated as the unifying symbol of “Indianness,” and has even been used as a motif for international events like the BRICS 2016 and G20 2023 Summit, among others.

“Visual production performed by marginalized groups are rendered invisible and do not “qualify” for the Indian visual communication canon.”

The work of oppressor caste illustrators often reflects the underlying meanings of purity and homogeneity synonymous with Brahmanism, while simultaneously showing their unwillingness to engage with complex caste realities. For example, the tilak (horizontal lines on the forehead used by Brahmans) is drawn on an illustrated animal mascot to signify that it is an intelligent being, and many use the ubiquitous swastika symbol, which symbolizes the sun, prosperity, and fortune in Hinduism. This unmarked or seemingly insignificant aspect of the casteist visual language enables illustrators to produce strikingly visible casteist forms while making them seem almost unseen. On the other hand, other forms of visual production performed by marginalized groups are rendered invisible and do not “qualify” for the Indian visual communication canon.

Who controls the narrative on casteism?

Design or creative methods of reproduction like hand-painting, screen-printing, and traditional offset printing, among others, have been dominated by artists, craftspersons, and laborers from marginalized castes systemically forced to engage in them. Even though affirmative action in the form of Reservation Quotas have been available in public educational institutions since the 1950s, students from marginalized castes rarely get into these schools because of the systemic inaccessibility to education. The literacy rate among them is low, and so is that of primary school enrolment. Furthermore, out of over 1900 design schools, only 250 are public. The rest offer private education with expensive tuition and no preferential access for marginalized groups. This status quo results in the under-representation of designers from marginalized castes, since the actual labor of creative methods of reproduction are not considered as “design practice,” and there are not as many designers from marginalized castes graduating from design schools.

Unfortunately, it’s difficult to find the data confirming the inaccessibility to these institutions, or the lived experiences of marginalized students who face casteism while attending them. During my research, I approached several design schools asking for demographic data of the student and teaching body. However, my requests were either ignored or insufficient/irrelevant data was provided, despite invoking the Right to Information Act. Excuses such as “convocation ceremonies” or “disruption of daily activities” were cited for evading providing accurate data on the curriculum and the demographics. Against this backdrop, there are testimonies of the increasing community of anti-caste designers reporting the lack of Dalit, Bahujan, or Adivasi professors in their respective schools—accompanied by an ever-present sense of alienation.

“In the current political climate, with the right-wing government promoting Hindu nationalist policies and escalating violence, anti-caste activism is considered a form of ‘terrorism.’”

The lack of representation and the hegemonic Brahmanic narrative translates into the content of design courses. Throughout my studies in the mid-2010s, we never discussed Jaati/varna (caste) as an inherent marker of Indian society—it was rendered invisible. During the design history module, my professor assigned me to hand-draw an infographic of Indian design history based on a book chapter on the formation of National Institute of Design (NID). The text reproduces the nationalist narrative according to Nehru’s government, which intervened to “save the craft and cottage industry” by training the then-NID students in Indian traditional handworks such as carpentry or textile. Few artisans from marginalized castes—who for generations were confined to their trade and deprived of education and social mobility—were hired to train people like my professors. At the end of the training, the artisans were still artisans, some of them employed as Associate or Assistant Lab supervisors, while the students graduated to become full-time professors and design consultants for the Indian government. Of course, the article didn’t mention any of this. While sitting and scribbling this tainted version of design history, I saw these missing parts but lacked the resources to address and articulate these problems publicly, fearing backlash and a negative impact on my grades. Moreover, in the current political climate, with the right-wing government promoting Hindu nationalist policies and escalating violence, anti-caste activism is considered a form of “terrorism.” Speaking up often results in far-fetching consequences, from intimidation to arrests without access to legal support.

Fighting back – the desire for liberation

Despite persecution campaigns against anti-caste activists by the national political regimes ranging from the centrist Indian National Congress Party to the ruling, fascist BJP, creative production has served as a resistance tool. From truck graphics, books, and protest art to political periodicals, marginalized castes have been fighting back and using design in their struggle for representation and liberation.

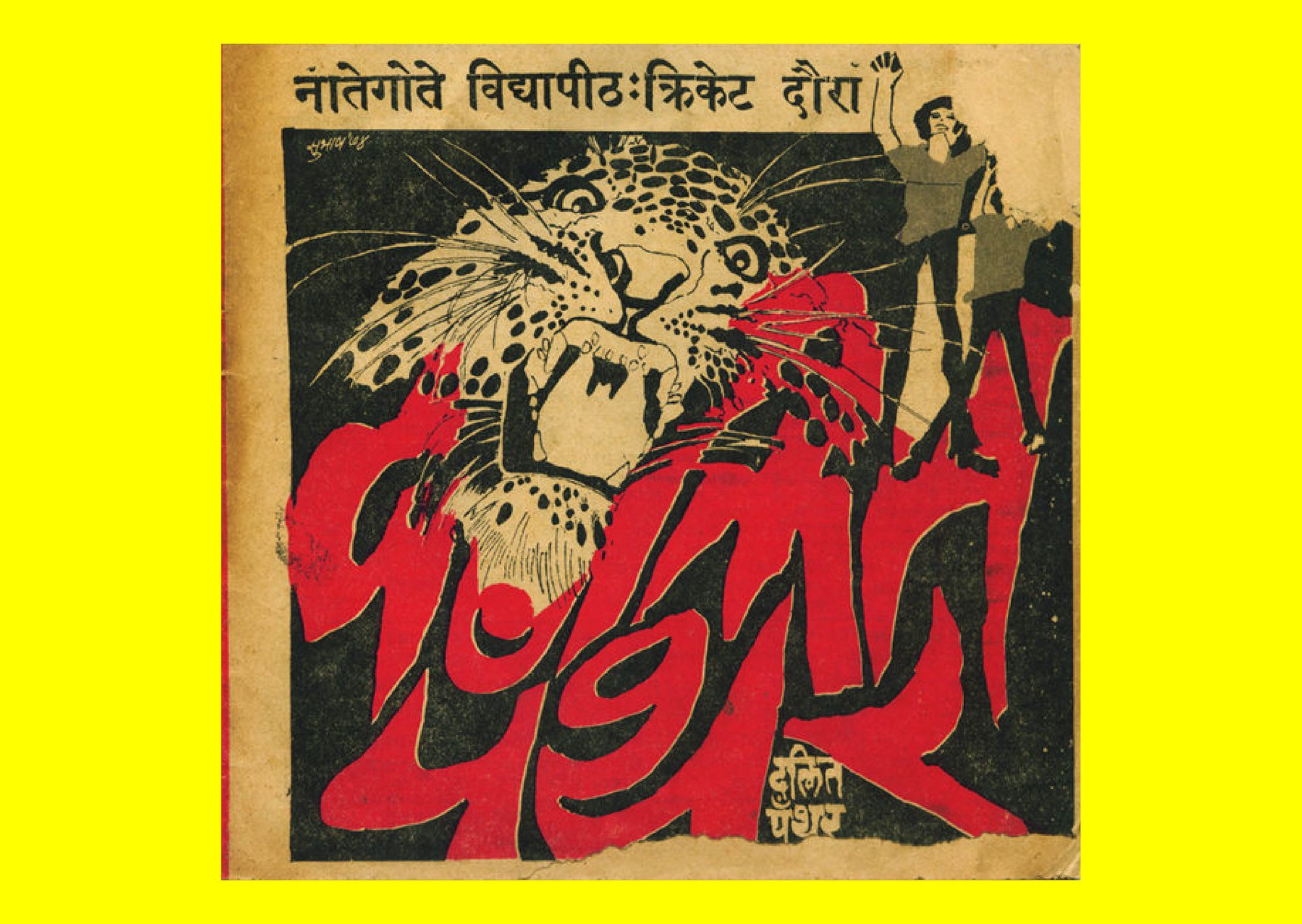

When Mumbai saw a spontaneous rise of the Dalit Panthers in 1972, artists and writers like Namdeo Dhasal, Raja Dhale, Arun Kamble, and J. V. Pawar resisted caste discrimination through their poems, visual design, and writing. Seminal publications like Chakravarty, Vidroh, Ata, Rawa, and Samuha were crucial texts of rebellion contributing immensely to India’s Little Magazine Movement, which emerged in the 1950s. For example, Vidroh (“Revolt” in Marathi) contained descriptions of Dalit oppression and their revolutionary fight against the violence of untouchability. Raja Dhale designed the publications by conservatively using monochrome and double-hue treatments since printing in four pigments was pricey and inaccessible. Often, the title or the cover used a single color like ultramarine blue or crimson, accompanied by all the text in black. Printing is a crucial and expensive part of design that compelled Dhale to use colors frugally to create a lasting impact. The famous artwork with red hand-drawn Devanagari lettering of the words Dalit Panther with black artwork of an angry panther is evidence of these Dalit artists’ spirit to utilize design methods to experiment with a medium and add to India’s visual language. Using bold, hand-drawn, “crude” folk art style and “imperfect” geometric, and rural imagery and typographic styles, these artists challenged the dominant Brahmanical visual language and the tenets of modernist design.

The resistance through design wasn’t limited only to academics. Working-class laborers from marginalized castes trained in industrial painting—including painting buildings, cinema posters, painting highway lines, and railway roundels—form a crucial aspect of the Indian visual landscape and reflect their desire for liberation. Truck graphics in India are not only delightful and colorful, but they also depict slogans of respect, precautionary messages about traffic rules, attractive hand lettering, and motifs of flowers, women, trees, or birds. Truck graphics essentially resist the Brahmanizing of such elements. For example, an elephant’s head is simply an elephant’s head, rather than the depiction of the Hindu god Ganesha. These trucks are like magnificent canvases for artists and laborers from marginalized castes, as they could never formally educate themselves in fine arts. They reflect their yearning for freedom as they meticulously paint every inch of the truck, which will become the truck driver’s home for weeks as they transport goods from one corner of the country to another. These above-mentioned designs represent the majority of the Indian populace—those that do not belong to the oppressor castes—but are yet to become a part of the curriculum in design schools.

The rise of digitality and social media’s omnipresence has intensified the resistance. This fight for liberation has taken over digital platforms by enabling anti-caste designers to connect and take the movement forward. The digital natives’ generation has taken over the baton, and is now redefining Indian visual design while continuing to tell anti-caste stories and histories. Last year, when we celebrated Ambedkar Jayanti (Dr. Ambedkar’s Birth Anniversary), my Instagram feed exploded with artwork from across the country. It is my happiest memory of 2022. I felt so overjoyed seeing the artwork that people from the community were uploading every few minutes! Oil paintings, pastels, charcoal, colored pencils, digital works—you name it. All were coming from the community—our community. “This is finally happening,” I thought. “Our culture is out there. India’s actual cultural representation is happening in real time!”

Bao (she/they) is an independent illustrator and researcher whose work focuses on redefining Indian design education from the anticaste perspective. Their research highlights the missing connection between Indian illustration and casteism. Through her work, she attempts to promote critical awareness among designers on how the very act of creative production in India is based on the experiences of Dalit, Bahujan, and Adivasi lives.

Title image:

We, the People of India, are the True Designers of this Country. (Illustration by The Big Fat Bao)

“The bricks to build cities on stolen land are made by Kumhars, beldars, rapaswales, jalaiwalas, and nikasiwalas. These are the various marginalized castes that are forced to engage in this specific occupation. What is it about their caste that doesn’t qualify them to be designers? If the act of designing is about product design and material exploration, isn’t this very activity of making bricks an act of design?”