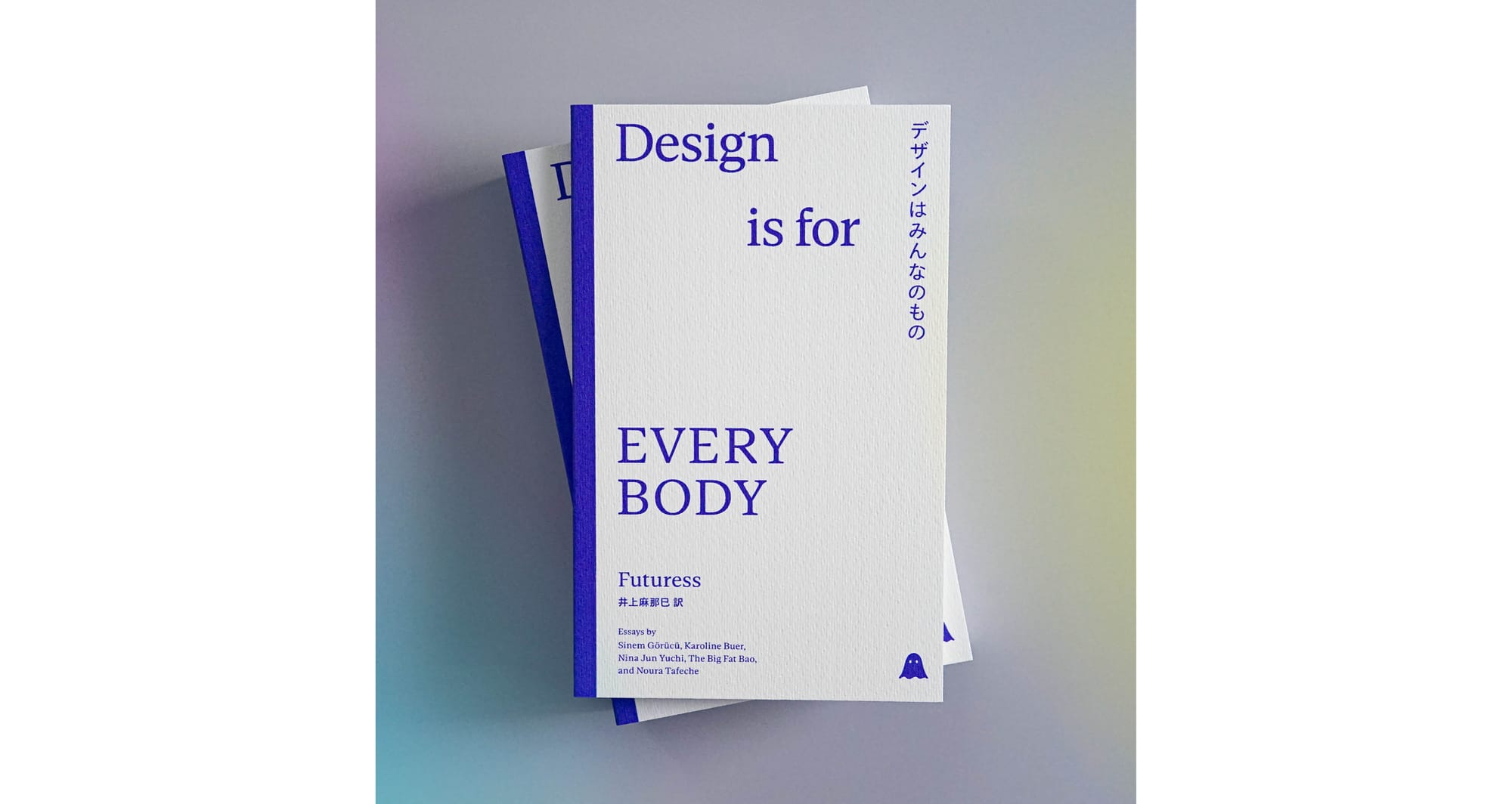

In early 2024, Futuress was approached by the Japanese publisher Troublemakers with the idea of translating some of our texts into Japanese and publishing it as a small book. The book, titled デザインはみんなのもの (Design is for EVERYBODY), gathers five texts by Sinem Görücü, Nina Jun Yuchi, Karoline Buer, The Big Fat Bao, and Noura Tafeche, which were selected from the nearly 140 stories published by Futuress since its inception in late 2020. This selection does not claim to showcase the “best” or any other qualitative superlative of Futuress’ texts; rather, it reflects the ongoing struggles of feminist practices in the everyday lives. The publishers of this book, Manami Inoue and Yuto Miyamoto, were determined to offer the Japanese-speaking audience a glimpse into stories born from the urgencies within the Futuress community, particularly those that relate to the contemporary urgencies of the Japanese audience.

Writing the book’s foreword became an opportunity for us, as editors of the platform, to reflect on the politics and promise of translation as a feminist practice. Our translated essays are not meant to be representative, nor do they aim to establish a canon. Instead, each story, to echo Sara Ahmed’s words, is a brick in the ongoing and unfinished project of building feminist worlds. Similarly, even though this foreword was written with the Japanese book in mind, it reflects a broader understanding of translation as a relational practice. Translation, in this sense, is not merely about bridging languages, contexts, and audiences, but about creating pathways for solidarity—about learning to speak alongside, rather than for, each other, and about strengthening ties with other practitioners and thinkers. This practice was already initiated in 2022 through our ongoing collaboration with the Brazilian magazine Piseagrama, whose texts we have been published under the TRAVESSIAS—CROSSINGS vertical; it has now expanded through this collaboration with Troublemakers, and is set to continue with more collaborations on the horizon. These efforts are not endpoints but waypoints—reminders that feminist publishing, much like feminisms, are practices of holding space for multiplicity, transformation, and collective reimagining.

Translation is a feminist practice. It is a labor of care, reaching across boundaries to listen, hold, and carry meaning from one place to another. To translate is to assert that no voice is too distant, no story too unfamiliar, no knowledge too obscure to be shared. It is an act of generosity and humility, a recognition that the boundaries of one language, one worldview, or one system of meaning are not the boundaries of what can be thought, felt, or understood. The English word “translation” traces its origins to the Latin translatio, composed of trans- (“across” or “beyond”) and latus (“to carry” or “to bring”). At its core, translatio evokes the image of something being carried across—like a river’s current transporting a leaf to its opposite shore. The verb “to translate” retains this sense of movement, of crossing thresholds from one space to another. But translation is more than just a crossing; it is a transformation, a reimagining.

“Language is never neutral but inherently political—shaped by histories of power and oppression.”

It is an act imbued with a feminist promise: the promise of bridging divides; of making meanings accessible across differences; of weaving political, cultural, and affective alliances that transcend the confines of language and the borders of nation-states. It acknowledges that language is never neutral but inherently political—shaped by histories of power and oppression. Translation, in its deepest sense, holds the power to reconfigure relationships, to expand the reach of voices, and to build solidarities that reshape how we imagine and create shared futures.

At Futuress, we deeply believe in the transformative potential of this promise. As a hybrid—part publishing platform, part learning community—for feminisms, design, and politics, translation is embedded in our daily practice. Our texts are written across disciplines, engaging with design topics through a feminist lens and revealing design’s role in sociopolitical issues. Although we currently publish only in English—a reality we hope to change in the future—English is not the first language of the majority of our contributors, authors, and editors. With our authors spread across five continents, this global dispersion brings complexity to our work: even within English texts, our editorial process is one of constant navigation and translation between languages, cultures, localities, and individual experiences. We engage in the intricate task of bridging, asking political questions about how much explanation and contextualization should accompany the text. We consider the power dynamics at play: does explaining too much or too little perpetuate certain hierarchies? Why are terms from hegemonic cultures often left unexamined, while those from marginalized ones are overly explained with footnotes and caveats? What terms are not translatable and better kept in their native language? As editors, we take a deliberate political stance, choosing not to over-explain, while remaining committed to making our texts accessible to a broad audience.

This stance is intimately connected to the promise of translation, which implies an external bridging. Here, we believe that the act of connecting is not merely a spatial movement—where the texts you read travel from places like Brazil to the USA, Argentina to South Africa, China to India, Norway to Palestine, Turkey to Zimbabwe, and more, into your homes, cafés, buses, and trains, or wherever you immerse yourselves into our authors’ stories. More importantly, through this mobility, these feminist stories transcend their origins; they cease to be mere stories from one place and become part of a growing force, a movement that crosses and pollinates different localities and spaces.

“Translation holds the hope of connecting beyond what is said.”

Additionally, bringing Futuress’ work closer to different linguistic audiences holds a personal significance for us. As a German-Japanese who mainly grew up speaking German, Mio’s “lost Japanese” often created a sense of disconnect and a desire to build bridges otherwise. As an identity that is called ハーフ (“half”) in Japanese and that is broadly connected with notions of in-betweenness and division, reading other diasporic stories and connecting through the disconnect is a way of acknowledging that the in-between—the bridge—can be a community space on its own, one that is shared and inhabited by many with different cultures and stories. As author Gloria Anzaldúa writes in the foreword to this bridge we call home, “to bridge is to attempt community.” Simultaneously, reaching out to a Japanese audience through translation is an act of reconnecting otherwise—a reconnect that, rather than seeing a lost language as a barrier, acknowledges that conversation is more than words. In this sense, translation holds the hope of connecting beyond what is said.

Maya navigates multiple linguistic realms daily, continually asking what it means to inhabit different languages simultaneously. What does it mean to try to relearn Yiddish, a language lost two generations ago? How does the constant switching between English, Hebrew, French, Spanish, German, and Polish—ranging from mother tongue to fluent, to adopted languages like Spanish, charged with love and familial ties—transform her? Does each tongue make her a different person, or, as Buenos Aires-based author Mónica Zwaig suggests, does it evoke a kind of rootlessness? Zwaig, who writes in rioplatense Spanish—a mother tongue she never fully learned as a child—calls it “a question of honor already, not to have arraigo.” Language does not merely express; it shapes and displaces, carrying its own affective weight. It is not only about words but about how they hold us, even as they elude us. Translation, then, is not just the act of crossing from one language to another; it is a worldmaking practice—to translate is also to transform.

“Translation becomes a form of political activism, a deliberate intention to create connections that originate in the local but extend far beyond immediate sociopolitical contexts.”

At Futuress, translation is central to our work. It allows us to weave connections between feminisms, design, and politics across contexts and continents. Community lies at the heart of Futuress’s work. Following the insights of our beloved author and scholar Sara Ahmed, we see “feminism as a building project.” The act of translation represents a step closer to the promise of feminist world-making, bridging worlds, creating movements, exchanging political ideas, and fostering learning across differences—the promise of the otherwise. This movement underscores the transnational potential of feminist politics, creating bridges, blocs, unions, networks of solidarity, allyships, and collaborations. In this way, translation becomes a form of political activism, a deliberate intention to create connections that originate in the local but extend far beyond immediate sociopolitical contexts.

Feminist translation therefore carries with it a responsibility—not to erase differences but to honor them, to make space for multiplicity while bridging divides. In this way, translation becomes a tool of solidarity, a means of building alliances across borders and fostering a collective politics of care. It offers a way to imagine and enact feminist futures—futures in which knowledge circulates freely, voices long silenced find resonance, and connections are forged not in sameness but in the shared commitment to justice.

“Translation aims to facilitate movement between different systems of thought, a radical unlearning of dominant norms, and new alliances.”

In this light, translation becomes more than just a linguistic exercise—it is a promise, and it allows us to forge new possibilities for design history, practice, and education. In this promise, we draw on the metaphor of Gloria Anzaldúa, who, in her seminal work Borderlands/La Frontera, speaks of living on two opposite shores at once. Anzaldúa emphasizes the transformative power of bridging them to cultivate a new consciousness. Similarly, translation aims to facilitate movement between different systems of thought, a radical unlearning of dominant norms, and new alliances. While translation is rarely straightforward, and is often messy and fraught, it is in that very messiness that its transformative power lies. To translate is to embrace complexity, to sit with difference, and to imagine ways forward together.

デザインはみんなのもの–Design is for EVERYBODY can be ordered via Troublemakers publishing.

小島 澪 Mio Kojima (they/them) is a German-Japanese design educator, editor, and researcher focusing on knowledge politics and social justice in design. Drawing on collaborative, intersectional feminist, and decolonial approaches, Mio’s practice critically examines the spaces and conditions of educational and community-based environments, and aims to broaden the values and experiences centered within them. From teaching and facilitating to publishing and curating, Mio understands their work as a space-making practice that centers on criticality, community, and exchange. After participating in several Futuress fellowships, Mio joined the team in 2021 as managing editor and initiated the conversational format “Let’s Talk.” Since 2023, Mio is the co-director of Futuress, where they are responsible for curating the platform’s learning programs, conceiving compelling content on social media, supporting the Futuress authors in crafting their original stories, and securing the finances to steer the Futuress ship forward.

Maya Ober (she/her) is a converted anthropologist, designer, editor, educator, learner, and activist whose work reimagines academia and institutional life through a feminist lens. She employs diverse mediums—ethnography, poetry, film, images, curation, and more—to explore the worldmaking dimensions of listening, complaining, queering, and embodying. Believing in the socially transformative potential of education, Maya co-conceptualized Imagining-Otherwise, and initiated feminist curricula. In 2017, she founded depatriarchise design, which in 2021 merged with Futuress. Maya is a doctoral researcher and lecturer in social anthropology at the University of Bern, looking at feminist practices. Alongside Mio Kojima, Maya is the co-director of Futuress.

Title image: A collage with texts translated from or into English and published on the Futuress website along with images of the original publications or translated texts.

Left: Design is for EVERYBODY, published by the Tokyo-based publisher Troublemakers, with My Grandma is Not a Cyborg by Sinem Görücü, A Canon Misbound: Feminist Lessons in Print by Karoline Buer, Mutual Dreaming by Nina Jun Yuchi, On Caste: The Roots of Discrimination in Indian Design by The Big Fat Bao, and Pastel-Coated Violence by Noura Tafeche (original Futuress stories translated from English to Japanese).

Bottom center: TRAVESSIAS—CROSSINGS texts We Belong to the Land by Antônio Bispo dos Santos and Becoming Savage by Jerá Guarani, initially published in Portuguese by Brazilian magazine Piseagrama.

Top right: The fourth issue of the FEM TECH TALK zine by Seoul-based feminist community WOMAN OPEN TECH LAB, with A Critical Statement by Sophie Thurner (published initially by Futuress and translated into Korean).

Bottom right: Designing with/against Cherophobia by Ece Canlı, initially published in German by Missy Magazine (issue 60).