When I saw the German feminist magazine Courage for the first time, I was amazed. It was not because of its provocative and progressive topics, addressing issues in the late 70s and early 80s that are still pressing today. And it was not because of its diverse covers, which profiled a different female artist with every issue. It was the classifieds that caught my attention: a place where women-run cafés and feminist bookstores advertised themselves, where car repair courses were showcased, and feminist travel suggestions were shared. Women proposed living together for a summer, simply to exchange thoughts and collaborate on similar projects.

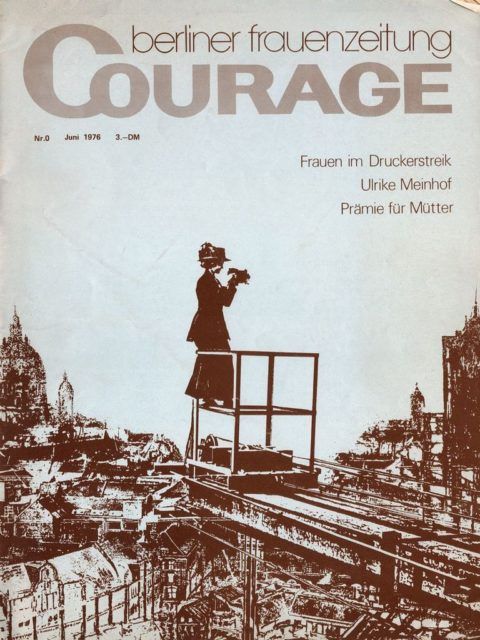

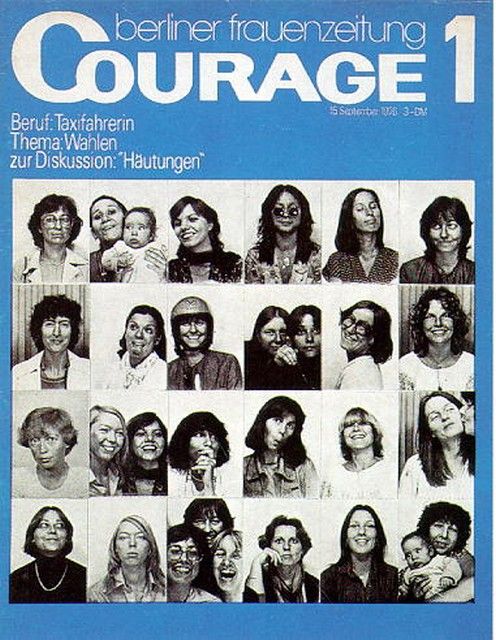

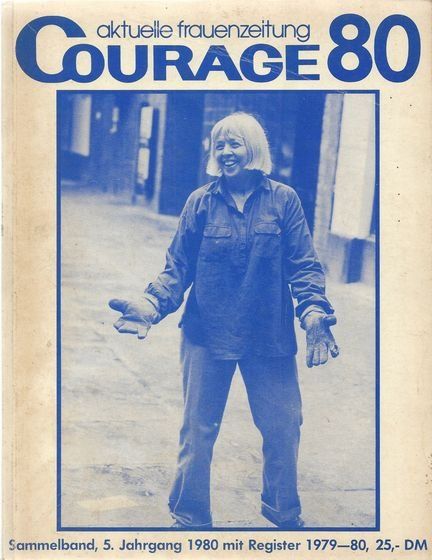

Three covers of Courage, No. 0 from 1976, No. 1 from 1976, and No. 80 from 1980.

I was energized by the mass of projects and the power of Courage’s vast network. I wondered how the editors of the German-language monthly, which in its first years could only be purchased in Berlin and later became available in other West German cities, man- aged to create these wide-reaching relationships, spreading from Germany to Japan and Canada? I tried to imagine how it must have felt back in Courage’s days. How the cities must have been, when women’s cafés, pubs, and bookstores gave feminism visible spaces. I wondered: where did all of that go? For sure, a lot of these networks have shifted to the internet. But what happened to the old-school places where a movement could physically meet?

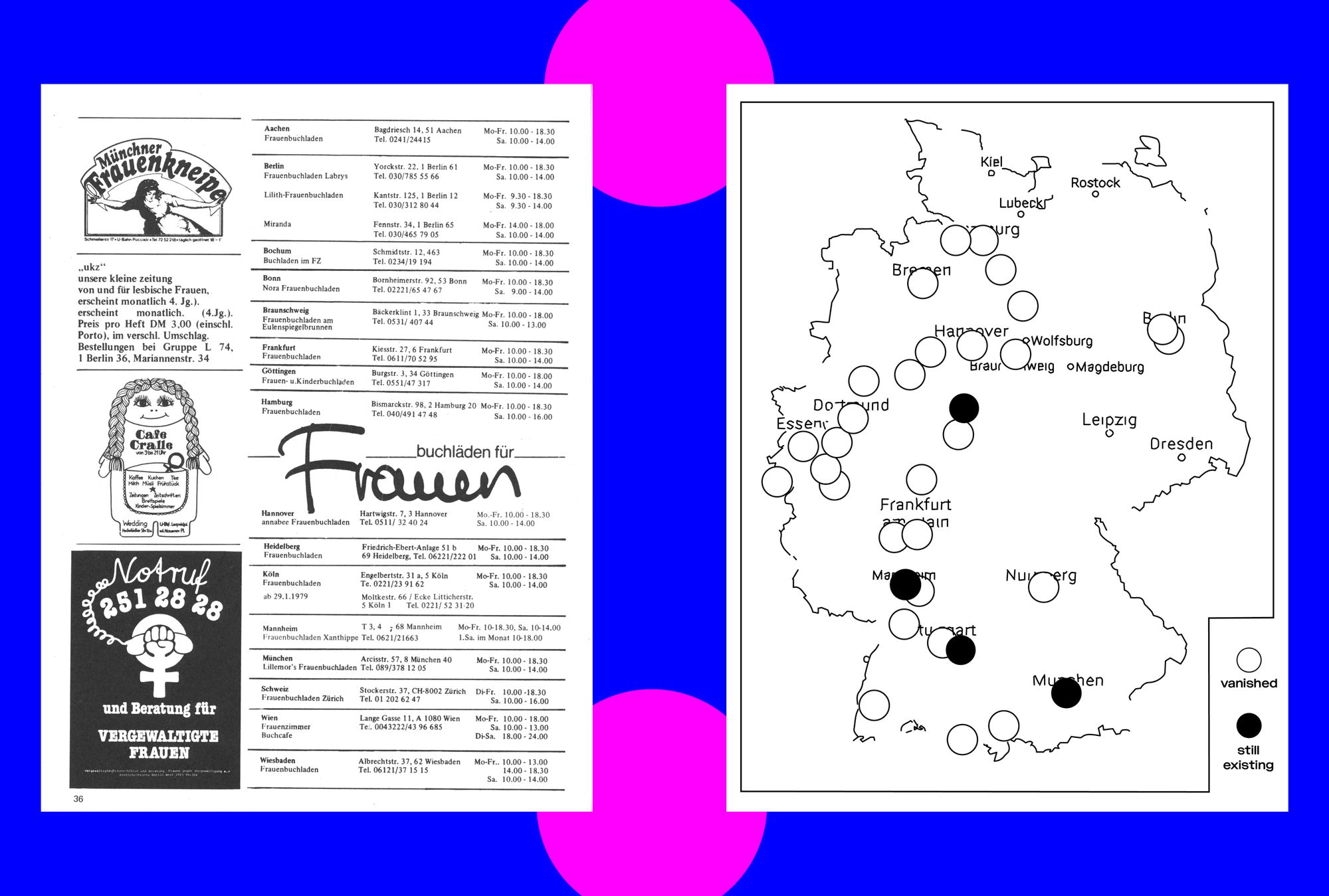

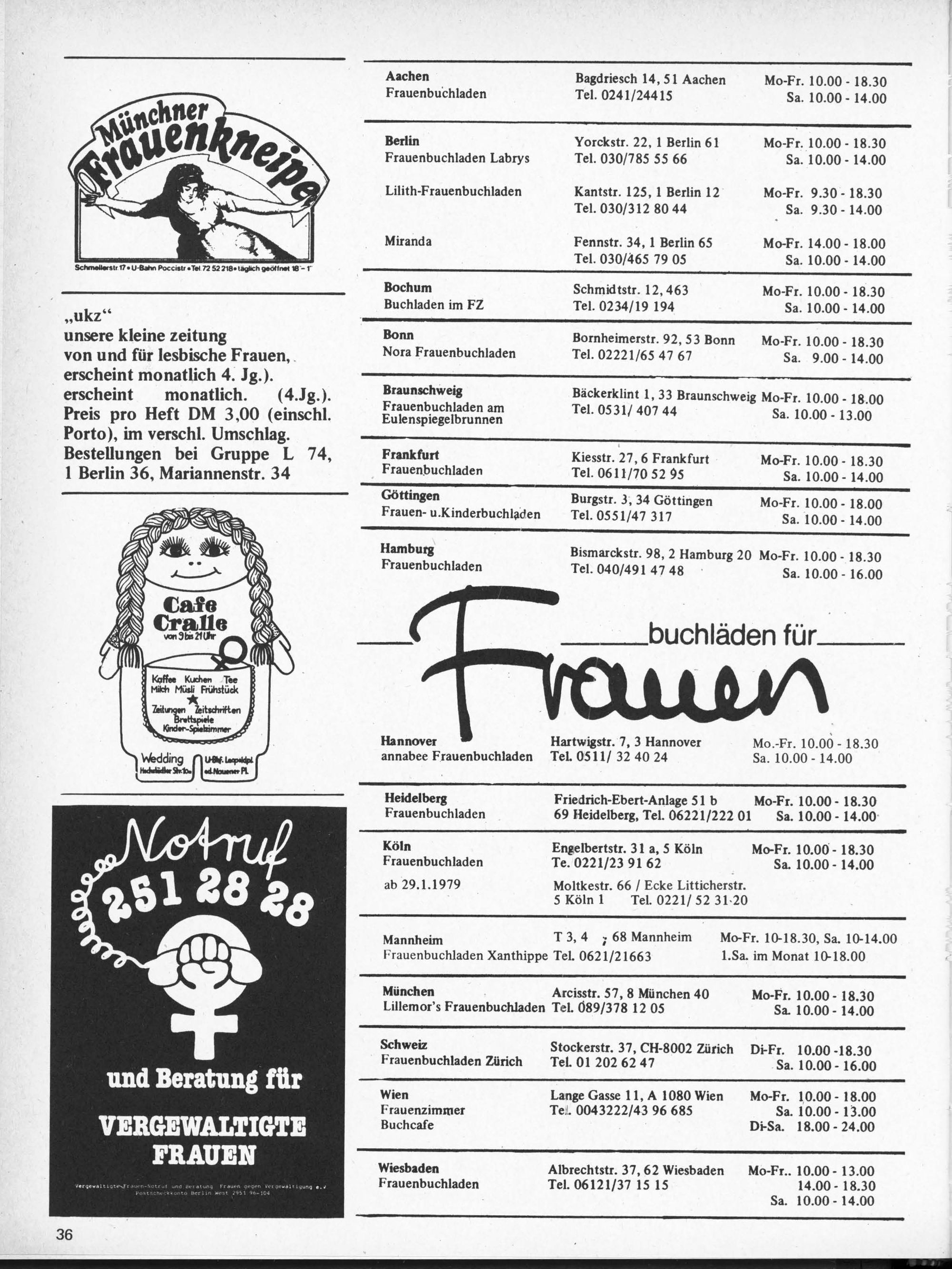

Extract from the classifieds section in Courage No. 2 from 1979, with a list of women's bookstores (left) and an itinerary with women's events (right).

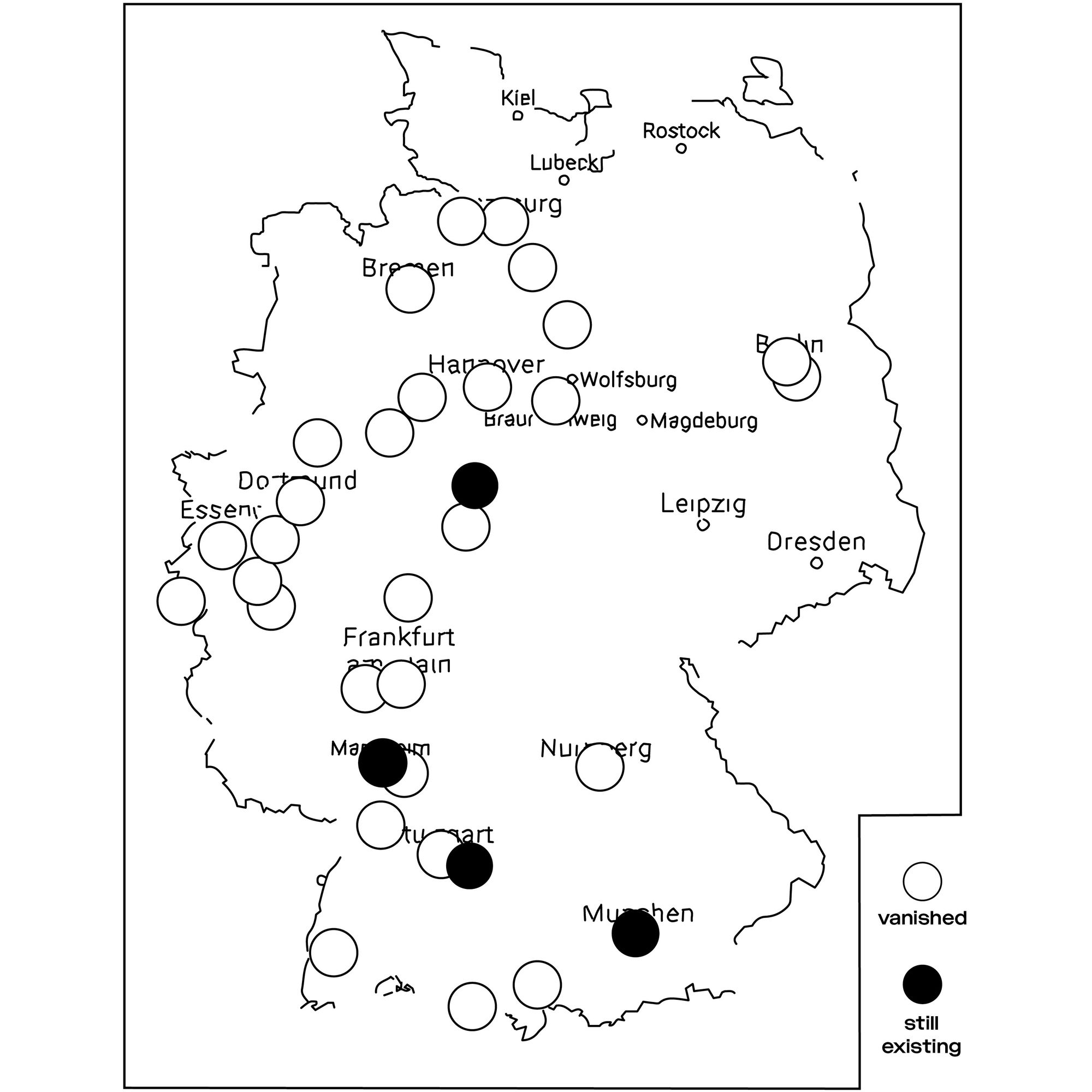

My scavenger hunt began with mapping the women-run businesses or spaces mentioned and advertised in the Courage classifieds—many of which have since disappeared. For instance, only four women’s bookstores out of over 30 that were founded in the 1970s are still around. All four bear women‘s names, some inspired by historical or mythical women—for instance, one bookstore in Mannheim is named after Xanthippe, the wife of Sokrates, and another in Tübingen refers to the last Amazon warrior queen, Thalestris. These four bookstores are among the few places that have remained since the wave of the second women’s movement.

On learning that many places from the Women’s Movement in Germany have disappeared, I began to look for comparable spaces existing today. I searched Google Maps using terms such as “women“ and “feminist”; I collected data through listings by feminist projects; I read articles on women’s bookstores; and I visited websites of women’s aid organizations. It wasn’t a straightforward or simple search. And neither is making sense of what I found.

I got a first impression of how the visibility of physical spaces has changed since the 70s when searching the term “Frauen” (the German for “women”) in Google Maps. Most of today’s pinned places are women’s aid associations. The oldest one, the Social Service of Catholic Women, was established by the politician Agnes Neuhaus as early as 1899. It offers counseling and help to at-risk women and families. More recent spaces labelled “Frauen,” however, seem to mostly be career guidance offices. My search results revealed few women’s bookstores, cafés, or other non-institutional spaces, which would offer people an informal meeting point. Unexpectedly, but actually unsurprisingly, most of the informal premises popping up were actually women’s fitness studios.

“Feminism has changed, and so has the language, discussion, politics, and mechanisms around women’s spaces in Germany.”

Feminism has changed, and so has the language, discussion, politics, and mechanisms around women’s spaces in Germany. For a fitness studio, for instance, women are mostly a consumer base. But what are their policies towards who counts as a “woman”? Are they being inclusive of trans women or non-binary people? Just because there’s the word “woman” in a company name doesn’t mean that the space is feminist. But neither does the reverse.

Some recent bookstores, such as Schanzenbuchladen in Hamburg, that appear in queer-feminist listings like Queer City Life, don’t actually label themselves using the word “woman” at all. Nor the word “feminism.” Neither do they clearly specify their political position, nor mention feminist literature on their websites. But their appearance in queer-feminist listings should be read as a sign that they affiliate with a queer-feminist cause. A lot of events mentioned in the same queer-feminist listings today also seem to take place in more general spaces that do not address women exclusively.

While the missing labeling might be said to make the Women’s Movement less visible, this move away from both certain labels and/or spaces is not without reason. Cis women’s spaces and cis lesbian women-only spaces have historically been important places for community building and political action, but they also created exclusion, especially for trans people. The words we use to name things carry meaning. Specificity can unite, but it can also harmfully divide.

“The words we use to name things carry meaning. Specificity can unite, but it can also harmfully divide.”

Tracing the places created by and for feminist women in the past, and feminist womxn and non-binary people today, led me on a trail where new forking paths constantly emerged. Instead of finding an answer to my question of where it all went, I above all discovered many new questions. How has the language of feminist labeling evolved since the 70s? How has second-wave feminist language been co-opted by businesses as a marketing strategy? What words are used today to signal when a space has an intersectional feminist agenda? My map of feminist spaces in Germany is waiting to be filled and continued. Rather than an ending, this is simply a starting point.

Go see the full interactive map and contribute to it!

Mio Kojima (they/them) is a German-Japanese designer and researcher. Growing up with different languages and cultures, Mio’s roots have led to a personal exploration of language and meaning, and their connection to world-building. Mio is interested in forms of co-creating of knowledge and collaborative practices, looking especially at the infrastructures of “coming together.”

This text was produced as part of the L.i.P. workshop, and has previously been published in the Feminist Findings zine.