“I embrace all of my sisters inside who have the courage and determination to break the rules and love women in prison.”

—Judy Greenspan, Sinister Wisdom, issue 61

“The fastest-growing sector consists of women—women of color. Many are queer or trans. As a matter of fact, trans people of color constitute the group most likely to be arrested and imprisoned. Racism provides the fuel for maintenance, reproduction, and expansion of the prison-industrial complex.”

—Angela Y. Davis, Freedom Is a Constant Struggle

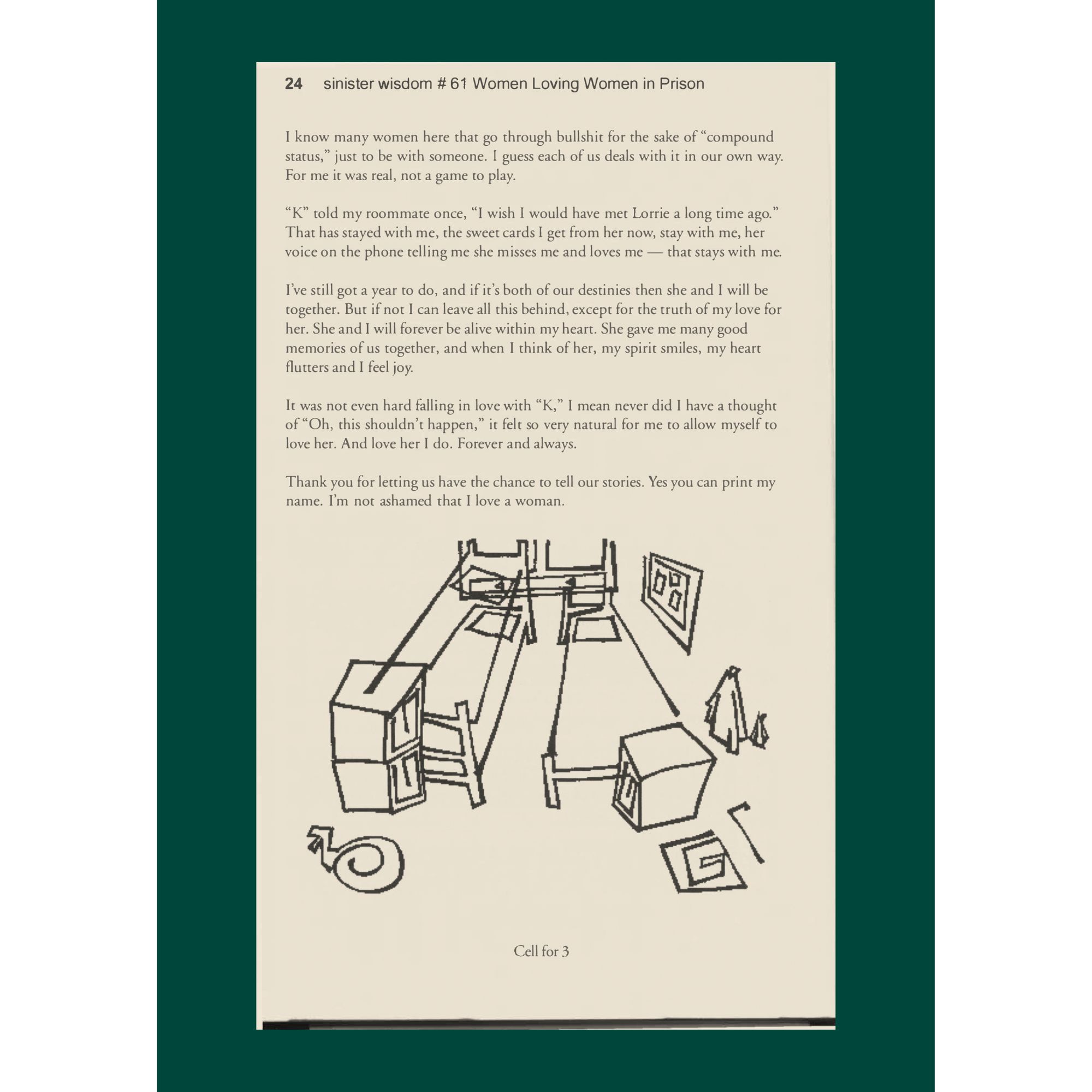

On the top bunk of a small three-bed cell in a US prison lies an expectant, and somewhat worn, copy of lesbian arts and literary journal Sinister Wisdom, casually waiting for its next reader. This scene may be fictional, but it’s based on fact. Or to be more precise, it’s based on a drawing, on a former political prisoner’s sketch published in 2003’s issue 61 of Sinister Wisdom, which was themed ‘women loving women in prison.’

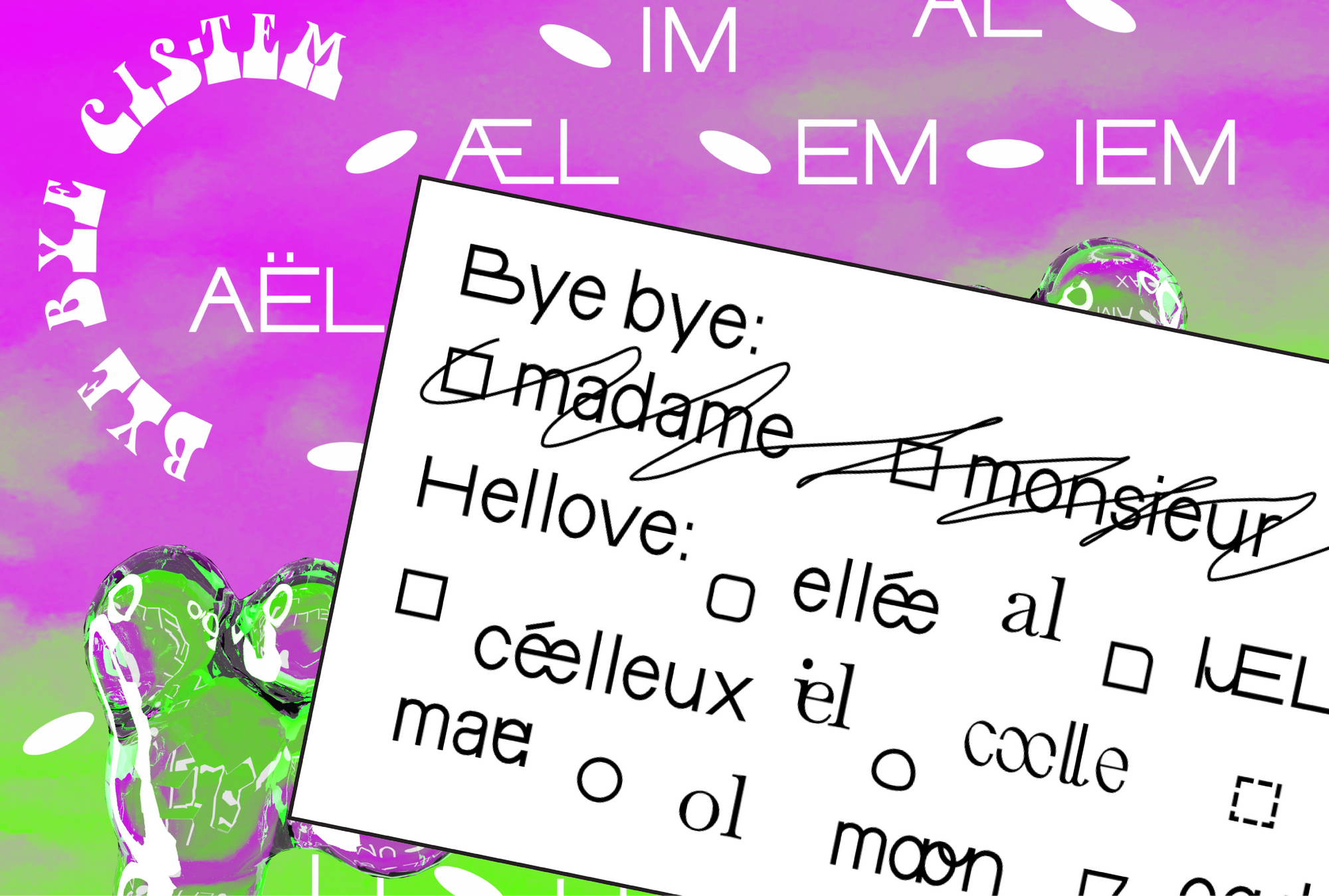

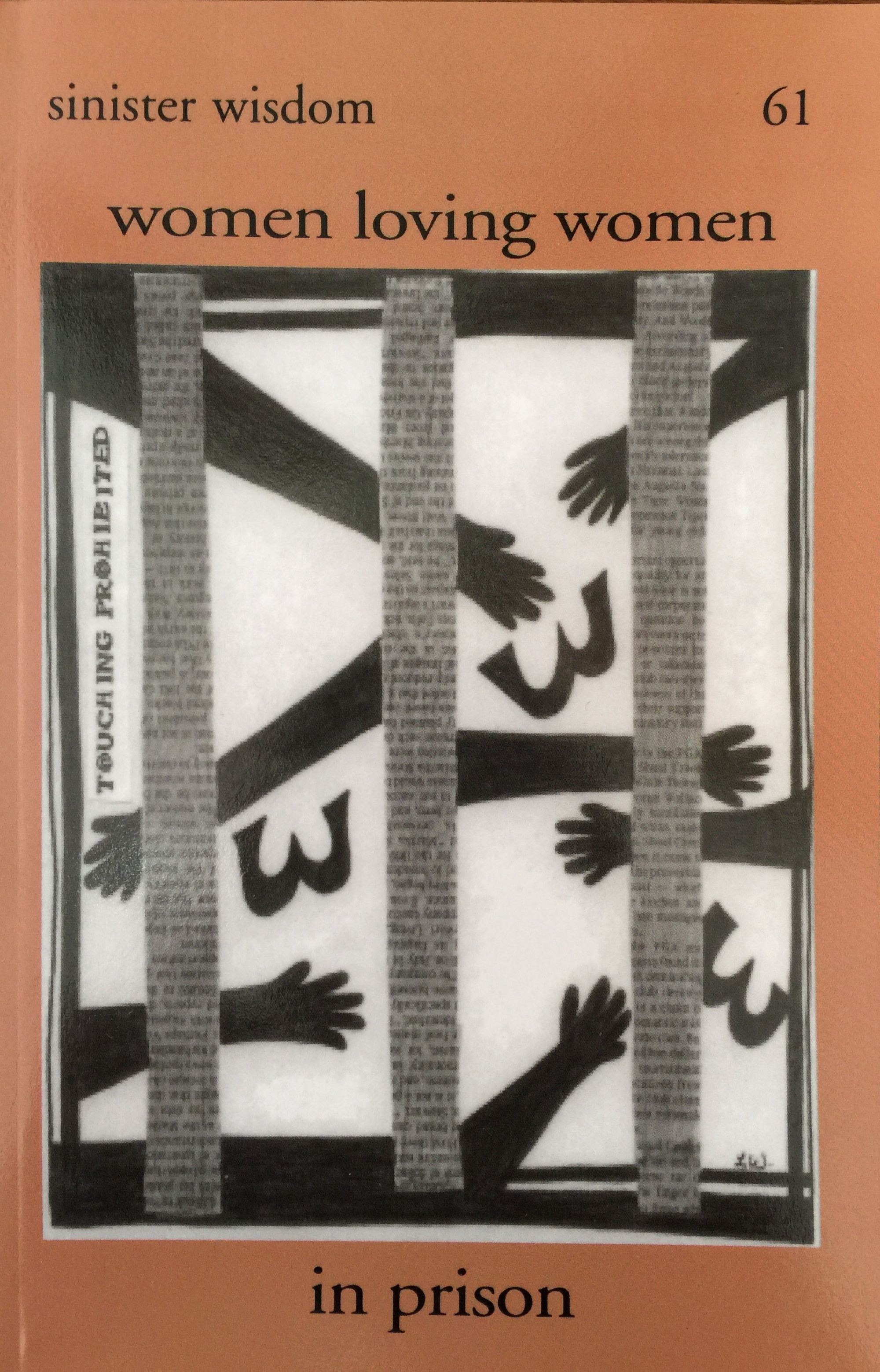

First founded in 1976 in North Carolina, during the wave of lesbian separatism, Sinister Wisdom continues to publish out of California to this day. Since the early 80s, when editors Adrienne Rich and Michelle Cliff began to move away from separatism towards intersectionality, the journal has given free subscriptions to incarcerated LGBTQ+ womxn. Today, that accounts for 15% of every issue printed. These first facts point to larger questions: What were and are the politics of the journal’s distribution? And how, still today, does Sinister Wisdom encounter, and attempt to bypass, the US prison-industrial complex, into the hands (and minds) of womxn loving womxn in prison?

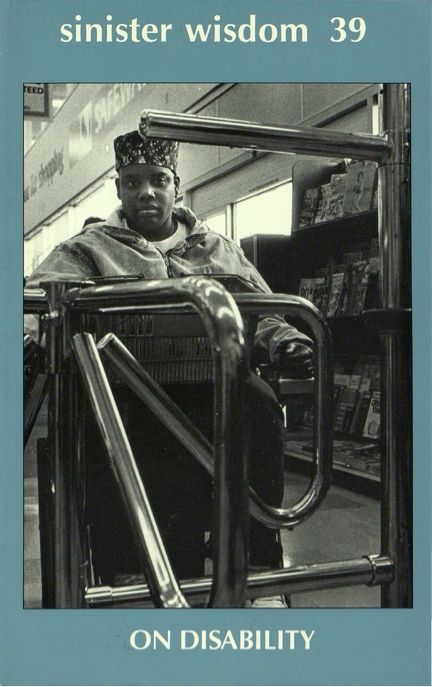

Three issue of Sinister Wisdom: Issue 61, themed "women loving women in prison," issue 39, themed "on disability," and issue 36, themed "surviving psychiatric assault..."

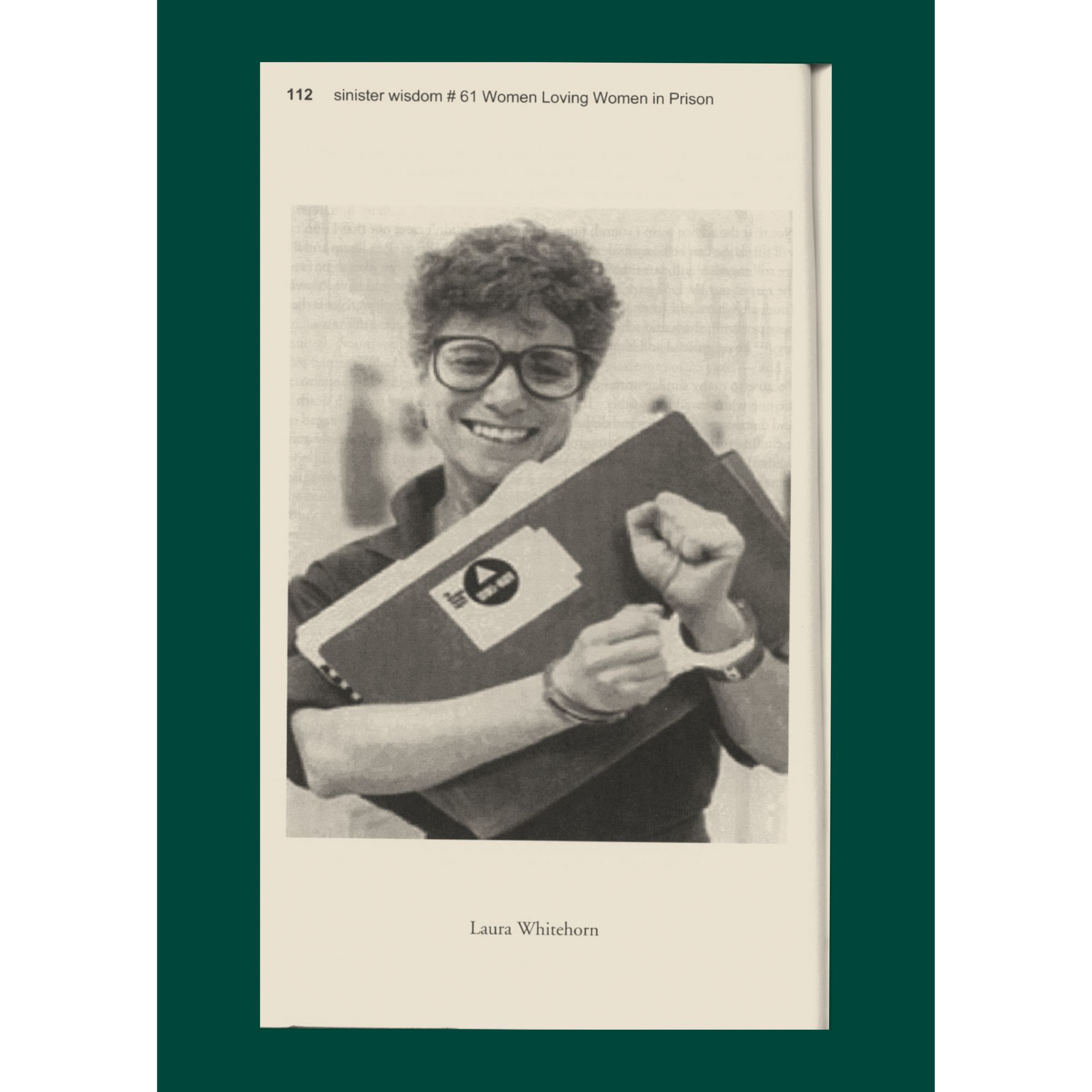

Despite fluctuating internal politics at Sinister Wisdom, there’s been a sustained dedication to exposing systemic oppression in both its writing and approach. This was especially clear during Elana Dykewomon’s editorship in the late 80s, where her conspicuous cover designs reflected a new approach in directly intersecting lesbian experiences with other forms of oppression. Her titles in this period included: ‘On Disability,’ ‘Lesbians & Class,’ ‘Lesbian Resistance,’ and ‘Surviving Psychiatric Assault.’ Dykewomon also introduced explicit opportunities for people to respond to forthcoming issues, enabling the inclusion of diverse voices who had lived experiences with the theme being explored. This participatory method paved the way for the ‘women loving women in prison’ issue. The aforementioned drawing—called ‘Cell for 3’—was penned by the formerly incarcerated Laura Whitehorn and pasted at the bottom of a letter in issue 61. The letter was written by Lorrie Flakes, who had been corresponding with Sinister Wisdom from prison at the time.

Over its many years publishing, Sinister Wisdom has navigated the liminal spaces and waiting rooms of prisons through a network of advocacy groups, who act as mediators and facilitators of queer correspondence in linking the journal with incarcerated womxn. Correspondence in the form of letters has historically served as a means for making connections when physical proximity has not been possible; not just by geographical distance, but also by social and political imposition. The exchange of knowledges between the journal and incarcerated LGBTQ+ womxn and QPOC goes beyond the gestural and becomes a political act.

For Sinister Wisdom, this political act begins the moment the journal is brought onto prison grounds. The journal is frequently stopped before it reaches its intended recipients—accused of being “too salacious,” as current editor Julie Enszer says. Sinister Wisdom dispute the charge and in every case appeal the decision, letting relevant ACLU (American Civil Liberties Union) groups know it’s being excluded because of queer content. Enszer told me:

“The journal gets kicked out of prisons all the time. There’s nudity. Some prison guard I think in North Carolina read the Beth Brant book [included in the selected works by Beth Brant issue of Sinister Wisdom]—like read the whole book—and kicked it out because there’s a part in a story where somebody whose being beat up by a police officer fights back. They thought that this was going to build rebellion and resistance among the women prisoners. And the scene is on page 131 or something like that, so it’s deep into the book…. This was a level of scrutiny and review that surprised us…. Usually, we get rejections and often I’ll tear out the offending pages that are cited. Then, I’ll send it back to the prisoner and write them a note saying you’re going to get this book without the offending pages. Sometimes we get the journal through that way…”

It is surprising but also not so: the US prison system is notoriously restrictive. It claims to censor material that threatens security, but the broad topics under censorship—ranging from acclaimed books by Black authors in one state, to generalized art history books in another—do more to repress knowledge and sever relationships with the outside world. When Sinister Wisdom, in whatever form, does eventually enter a prison, it becomes part of the social fabric of daily life—a transactional object. Often women ask for more copies to be sent to other prisoners, and on release ask for a continued subscription to help them with their transition into the outside world.

I’ve been imagining scenarios in my head of womxn reading, writing, exchanging, and interacting with the journal in spaces like the one drawn in ‘Cell for 3.’ These little acts subtly subvert the oppressive and patriarchal nature of the journal’s context, by simply allowing it to take up space and render visible what is usually obscured. Perhaps the prison guard in North Carolina was right in thinking Sinister Wisdom might build resistance.

Phoebe Eustance (they/them) is an interdisciplinary artist-researcher. Their practice is inspired by queer theory and explores conditions of space and labor in relation to institutional models of care.

This text was produced as part of the L.i.P. workshop, and has previously been published in the Feminist Findings zine.