“I asked my friend Penny, who is my childhood friend, if she would be interested in doing a new magazine,” says Liza Cowan about co-founding DYKE A Quarterly, a lesbian separatist periodical published in New York City during the 70s, together with Penny House. “As kids we loved magazines. So she said yes and we decided to do it.” Together they published a total of six issues over a period of four years.

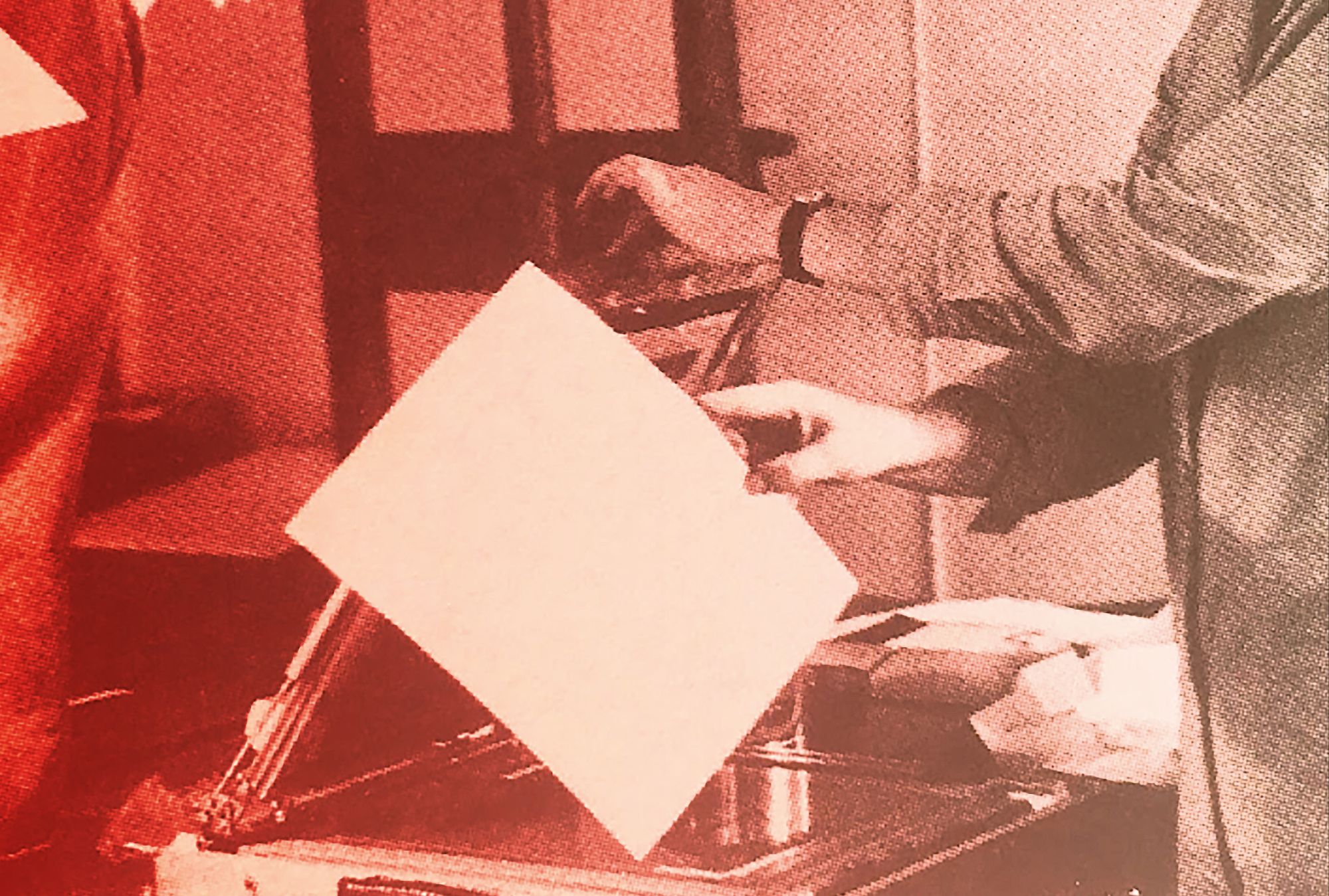

It’s May 2020 when I interview Liza Cowan. From her Zoom thumbnail, she explains to me how, when the magazine started in 1975, a time when personal computers were not yet common, most of the design had to be done by hand. Aware that they were capturing a certain moment in history, Cowan and House chose to represent the time and energy around them with splendid, carefully considered graphics, rich in detail, printed on quality paper, predominantly in red, white, and black ink. As Cowan says: “If we’re building culture and we want that to last, we want it to be beautiful.”

“Aware that they were capturing a certain moment in history, Cowan and House chose to represent the time and energy around them with splendid, carefully considered graphics… .”

This determination isn’t alien to the general tone of the magazine, which can be characterized by its straightforwardness. Cowan tells me that DYKE was the only magazine at the time that bluntly stated, on its cover, that it was only to be read by women. Copies were sold in women’s bookshops, and if a man were to subscribe, his money would be returned. DYKE’s contributors—who were always paid—were all lesbians, as were the women in charge of the printing and distribution processes. Likewise, most of the projects, spaces, and artistic products mentioned in the magazine were also by and for lesbians.

“DYKE’s contributors—who were always paid—were all lesbians, as were the women in charge of the printing and distribution processes.”

Lesbian separatist feminism was created to benefit a minority group: women loving women. There is much to learn from such models of empowerment and engagement. However, from today’s perspective, it is important to acknowledge that at the same time as separatist projects centered the needs and lives of cisgender lesbian women, they also created exclusion— often of other marginalized identities, and most crucially, of trans women. In issue five of DYKE, co-editor Janet Meyers speaks of her “sense of active historical awareness” and reminds us how, when looking at women’s history, “one can’t select parts to respond to and parts to reject or revise.” As we look back to the past, we can’t pick and choose.

“…at the same time as separatist projects centered the needs and lives of cisgender lesbian women, they also created exclusion— often of other marginalized identities, and most crucially, of trans women.”

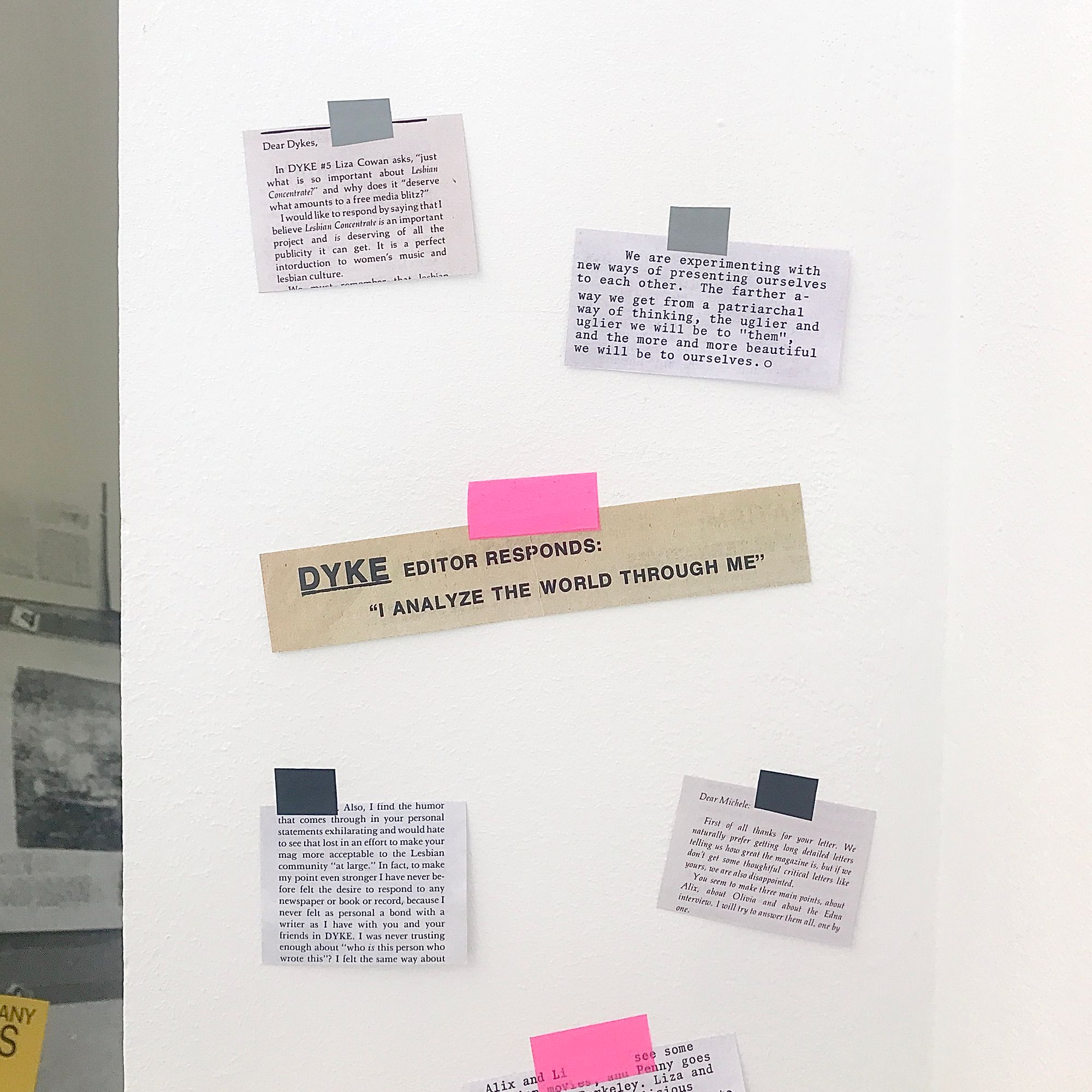

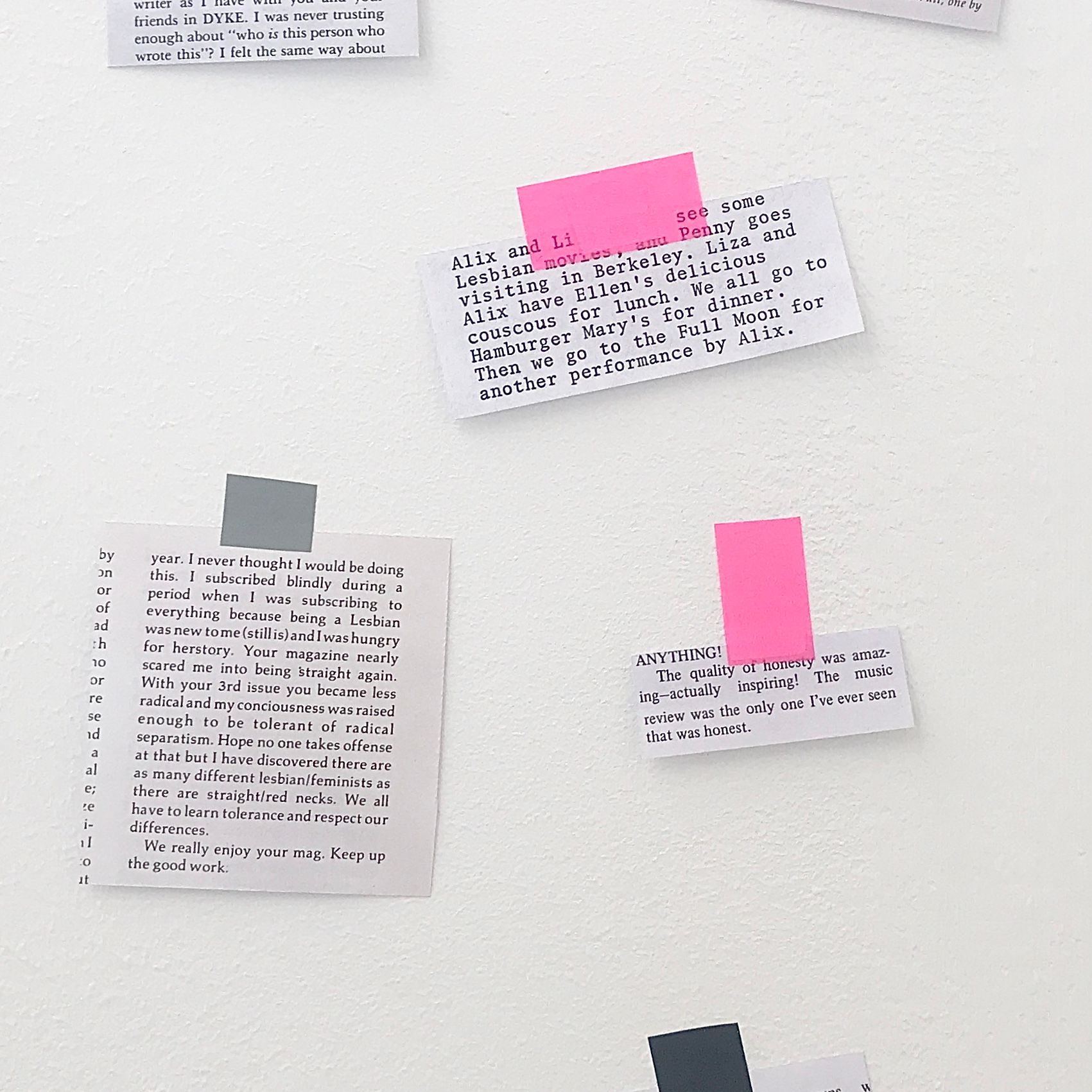

DYKE seems to hold in its pages a series of complex contradictions, which reverberate in the largely disparate opinions of its readers. While some readers had never felt such a deep connection to a magazine, others considered DYKE to be far too personal and, therefore, alienating or irritating. It’s possible to navigate the reader’s different feelings through what, according to Cowan, is actually the most interesting part of the magazine: Its letters. The goal of this section was to give a voice to the readers, so the letters represent a host of stories and are an example of the value of a space for dialogue and critique. Often, readers wrote in to comment on the highly personal nature of DYKE’s editorial content, which regularly focused on the editors’ own day-to-day lives and personal opinions.

“DYKE seems to hold in its pages a series of complex contradictions, which reverberate in the largely disparate opinions of its readers.”

Nancy, from Oklahoma, wrote in one of the letters: “The thing I like best about your mag is the personal touch. This is who we are.” Another reader, who signed her name as Lavender Scorpion, criticized how the editors “tended to state a personal opinion as if it were a fact.” Articulating her thoughts regarding this matter, Cowan becomes very assertive. “We wanted to make it clear that it wasn’t a universal lesbian point of view, because there is no such thing. It came out of a deeply personal history,” she says. “We were criticized for sharing our lives: ‘This is just gossip.’ And we were like, ‘Well what do you think history is?’”

Liza Cowan: “We were criticized for sharing our lives: ‘This is just gossip.’ And we were like, ‘Well what do you think history is?’”

There is something deeply political about women writing themselves into the story, and into history. As I absorbed myself in the pages of DYKE, I was slowly struck by how much of the past coexists with the present, and how, on a personal level, that realization was so foreign to me. Maybe because history books never told me the stories that this magazine tells in its articles, pictures, and advertisements. Maybe because, somewhere in the path of history, I lost touch with the many generations of lesbians who came before me and, despite being aware of that gap, I was too scared to find out how much or how little we have in common. However, speaking with Cowan and thumbing through the pages of DYKE was a precious push towards strengthening my understanding of the interconnectedness of the present and the past.

There is something deeply political about women writing themselves into the story, and into history.

As I bring my journey into lesbian history to a momentary close, I remember a passage by Rebecca Solnit from her book Whose Story Is This?: “It seemed, sitting there, that the city we both inhabited was a place full of overlapping gestures, of people looking backward and passing something forward, of the coherence of a storied landscape.”

Clara Amante (she/her) doesn’t know very well what she does, but she enjoys the freedom that gives her to do a little bit of everything. Currently, she works as a producer and researcher at Gerador, an organization that aims to promote cultural projects in Portugal. Recently, she was also a programmer for the International Queer and Migrant Film Festival in Amsterdam and a project manager for the Youth Artivists for Change project.

This text was produced as part of the L.i.P. workshop, and has previously been published in the Feminist Findings zine.