Creil, northern France, October 1989: Three Muslim adolescents—Leila, Fatima, and Samira—refused to remove their hijabs in school. Seeing their act as an insult to the country’s secular public school system, the principal decided to expel them. The incident, which became known as “l’affaire du foulard de Creil,” sparked a nationwide debate on issues of religious freedom, secularism, and racism.

While other French students followed the examples of Leila, Fatima, and Samira, the issue divided government politicians, intellectuals, activists, and even members of the Muslim community. One month after the incident, the Council of the State decided that expressions of religious beliefs could not be forbidden in educational contexts. The issue, however, continued to reverberate in the news for months. Then years.

“The national controversy, spectacularly supported by the media, transformed three young girls wearing headscarves into a machine of obscurantism.” — Souad Benani

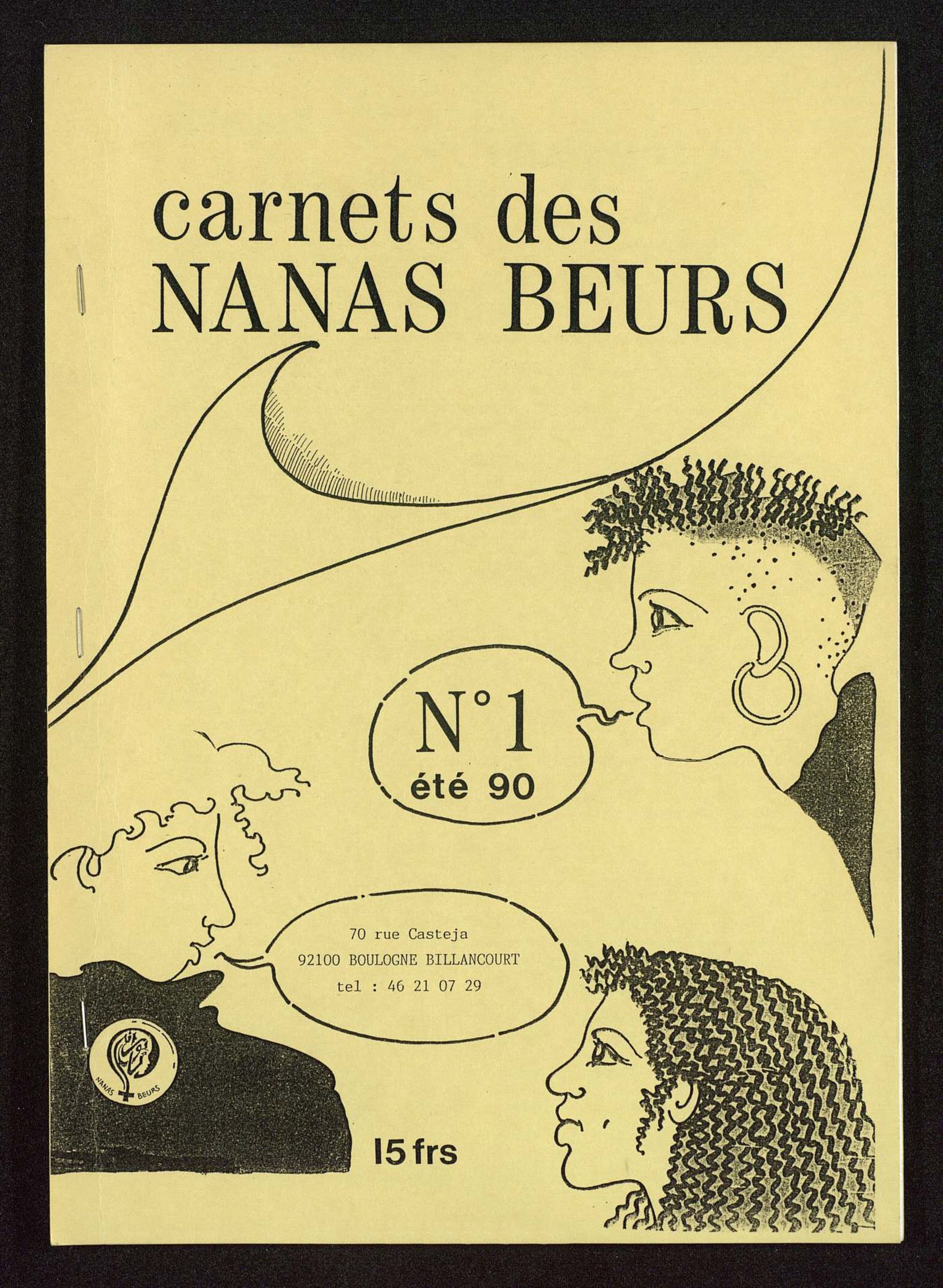

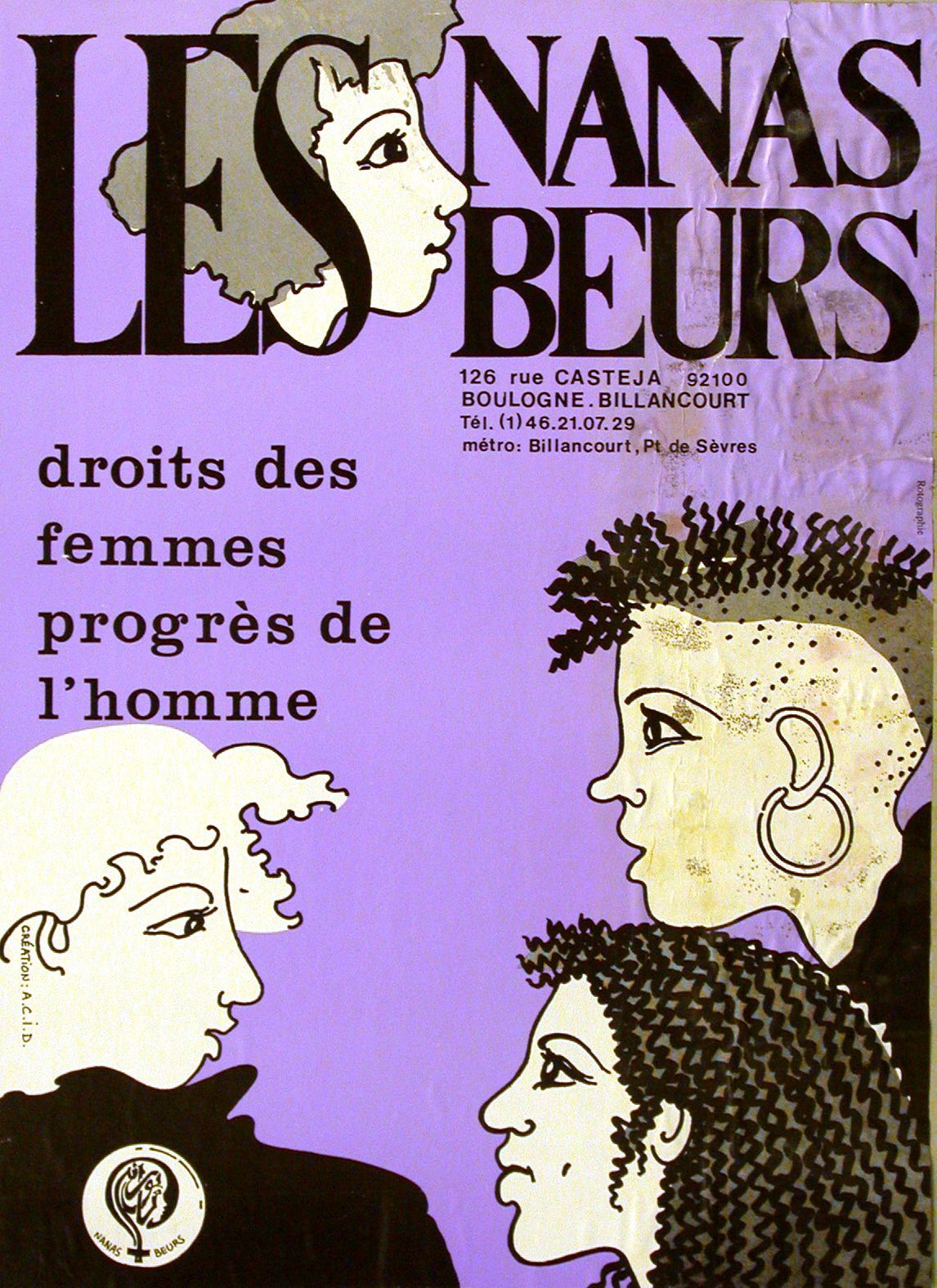

“The national controversy, spectacularly supported by the media, transformed three young girls wearing headscarves into a machine of obscurantism,” wrote teacher Souad Benani in the first issue of Les carnets des Nana beurs, a staple-bound, photocopied publication that came out in the summer of 1990, and which was fully centered around the issue of the hijab. “Nana” signifies a girl or a young woman. “Beurs” is a derogatory term for a second-generation immigrant born in France from North African origin—a term likely reclaimed in this instance. The journal was published by an association of the same name, Les Nanas beurs, which was presided over by Benani herself.

“We cannot overemphasize our commitment to the total liberation of women. Fighting against the wearing of the veil, against all fundamentalism, against confinement, the interiorization of women, is part of our fundamental principles,” continues Benani in her editorial. “But another fundamental principle to us is that of education. The majority of Maghreb women have been left out of knowledge for too long.”

“‘For or against the scarf’ is a false debate!” — E.M.A.F (the association of Magrebian female expressions)

Several contributions in the issue echoed Benani’s position, and defended the young women’s access to secular education. A letter from the Nanas Beurs association itself, penned by Hanae Benani, was also against the hijab, which it deemed to be a symbol of female oppression. At the same time though, Hanae Benani vehemently criticized the decision to expel the three students in Creil. Other contributions, however, focused more on the racist nature of the expulsion. “‘For or against the scarf’ is a false debate!” read a statement by E.M.A.F (the association of Magrebian female expressions). “The real debate is whether French society is so fragile that it cannot ask the real question: whether it has acceptance and respect for all cultural differences?” wrote essayist Fiammetta Venner, who accused the right-wing media of using the story to launch an anti-immigration campaign. “Three Hostages for a Masked War” was the title of another article.

“The real debate is whether French society is so fragile that it cannot ask the real question: whether it has acceptance and respect for all cultural differences?” — Fiammetta Venner

The Nanas beurs—national in its scope—was a feminist association set up in 1985 to fight against gender inequality and promote Maghreb culture. It aimed to create an inclusive, supportive space for young women who were often at odds with their families, especially their fathers and husbands. The Nanas Beurs also provided its visitors legal council, visa advice, mental health resources, and information on abortion.

“In the context of female immigrants of North African origin, that is to say, the young girls concerned with our association, the very term ‘feminism’ is disputed,” explained Benani in a 1991 interview. “That said, they have—without calling it feminism—similar aspirations. They want to have the right to live freely, to go out, to work. That is to say, not to be considered only on the basis of their gender.”

An illustration in the first issue of Les carnets des Nana beurs summarizes the intersections of oppression that the association hoped to address, for women, Benani believed, were caught between patriarchal attitudes both within their own cultural background and families, and in the wider context of France. A young woman in the center of the page is torn in two directions, pulled by a white, presumably French man on the left that says “Come sweep the faculty’s toilet,” and a Muslim man on the right that says, “come sweep the mosque.” The illustration echoes a sentiment of the E.M.A.F: “We will not be the guns of some, nor the shield of others.”

“We will not be the guns of some, nor the shield of others.” — E.M.A.F

In 2004, fifteen years after the initial incident, a law forbidding “ostensive religious symbols” in school was passed in France. It prohibits the wearing of any “visible” religious sign, which includes the Islamic veil and also the kippah, as well as large crosses. Two years ago, in 2019—30 years after the “l’affaire du foulard de Creil”—another public debate was launched. This time, it was sparked by an instance where mothers wearing the hijab during a school outing were harassed. It led the Senate to adopt an amendment to the law, a “school of trust” aimed at further prohibiting ostentatious religious signs.

Today, contemporary feminist discourse increasingly recognizes Muslim women’s agency in their own decisions; their right to identify and dress however they wish, and the extreme violence of policing a woman’s choice to wear the hijab. However, in the 80s and early 90s, this public debate was still taking shape. With its first issue, the Carnets des Nanas beurs offered more than a sense of nuance: It foregrounded the opinions of Muslim women themselves. After all, it was the actions of three young Muslim women, Leila, Fatima, and Samira, and their struggle and their resistance, that instigated the nationwide conversation in the first place.

“It is thanks to the encounter and friction of these plural ideas that a feeling of coming together, of unity in which I can identify myself, that is to say, a certain idea of humanity, is born.” — Soraya Hamdani

“Most of us, young women ‘beurs,’ have approached our culture and our identity in terms of emancipation,” writes the journalist Soraya Hamdani in another text published in issue one of Carnet des Nanas Beurs. She denounced the social pressure to assimilate, to integrate, to make her cultural differences disappear. “The culture that I evoke in terms of emancipation does not mean denying or rejecting one’s own heritage. In no case is it to cross out the history of our parents, because this is our heritage. It is by crossing the two cultures that we manage to live better in the interior than the exterior, to flourish.”

For Hamdani, the public and secular school was a space of freedom, where thanks to a common language, it was possible to understand each other despite diversities. “It is thanks to the encounter and friction of these plural ideas that a feeling of coming together, of unity in which I can identify myself, that is to say, a certain idea of humanity, is born.”

Eugénie Zuccarelli (she/her) was born in Paris. Since 2017, she’s studied design at École nationale supérieure des Arts Décoratifs.

This text was produced as part of the L.i.P. workshop, and has previously been published in the Feminist Findings zine.